Last winter, the two films I was most eager to see were Westerns: The Revenant and The Hateful Eight. In the case of The Revenant, the trailer made the film look spectacular. Knowing that the director was Alejandro González Iñárritu—much of whose earlier work (in particular 21 Grams) I quite liked—excited me all the more. As for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight, I’d been awaiting that, like many, for years. Though I found Tarantino’s previous film, Django Unchained, to be his weakest feature yet, I remained a huge Tarantino fan and could not wait to see what he would do with a second crack at the Western genre.

The late 2015 release of both films made clear that their studios considered them Oscar contenders. The Revenant, of course, did well by the awards, with Leonardo DiCaprio finally winning that elusive Oscar for Best Actor, Emmanuel Lubezki winning for Best Cinematography, and Iñárritu winning for Best Director. The Hateful Eight won one Oscar for Ennio Morricone’s score.

But the winter release was also appropriate because snow and cold and frigid landscapes predominate in each. The greatest thing about The Revenant is its visuals: the shots of snowbound forests, valleys, and mountains and the way its human interactions play out amid these magnificent settings. And though much of The Hateful Eight takes place inside a stagecoach lodge, the reason its toxic crew is gathered indoors for so long is to wait out a blizzard. I can’t remember another film I’ve seen where the sound of a howling wind made such an impression on me.

Overall, though, I must say that both films proved slightly disappointing. With The Revenant, I found the handling of the plot underwhelming; I was surprised at how bare and one-note it is. A man is wronged. A man overcomes arduous obstacles to get his revenge. The man has his revenge. The movie ends. Period. Tarantino’s film has more life—it’s funny, profane, full of twists, and gory (the usual Tarantino stuff)—but whether its views on American history and thoughts on racial strife hang together is another question.

Of the two, The Hateful Eight is the one I can see myself revisiting, even with its flaws (or perhaps because of its thought-provoking flaws), but at the same time, seeing these two films so closely together put me in mind of other wintry Westerns I’ve seen. Let’s call them a sub, sub, sub-genre. Four wintry Westerns in particular stand out to me. So as the weather turns and the snow begins to fall, let these films remind you that the West isn’t always scorching deserts and dry old towns.

Track of the Cat (1954)

On an isolated ranch in the Californian mountains, early in the 20th century, lives the Bridges family—and what a strange and dysfunctional family it is. Four adult siblings, three men and one woman, live with their mother and father. None of the siblings are married, and the family members bicker and argue constantly.

The older brother (William Hopper) is laid back and takes the gibes from the aggressive middle brother (Robert Mitchum) in stride, but he doesn’t like how the middle brother mocks and belittles their quiet younger brother (Tab Hunter). Neither does their sad and acidic sister (Teresa Wright), who enjoys the company of the visiting young woman (Diana Lynn) who wants to marry the younger brother if he can summon the backbone to stand up to his brother and their verbally abusive mother (Beulah Bondi). The mother dotes on the middle brother, and nobody pays much attention to the alcoholic father (Philip Tonge), a man given to eloquent monologues bemoaning his own ineffectualness.

Meantime, on the fringes, moving in and out of their house, is their old Native American ranch hand (Carl Switzer). He watches them with an unreadable face and seems indifferent to their quarrels. He is also a man obsessed with panthers because, once upon a time, a panther did damage to his family.

Track of the Cat is a weird amalgam of a film. It’s part overheated, Gothic-tinged family drama, part outdoor adventure story. While Mitchum and Hopper venture out into the snowy wilderness to hunt down a panther that’s been killing their cattle, the other family members remain back at home and go at each other with the kind of neurotic intensity only years of claustrophobic living can produce. They wouldn’t be out of place in a Tennessee Williams play. Expansive outdoor scenes alternate with scenes of indoor conflict. It’s an unsettling effect, and the viewer is kept on-edge throughout, readjusting repeatedly to two different narrative rhythms.

William Wellman directed the movie, adapting Walter van Tilburg Clark’s novel. Wellman had filmed Clark’s The Ox-Bow Incident in 1943. Although he used color this time around, the movie is shot as if working in black and white. Almost everything shown in Track of the Cat is some shade of black, white, or gray. This monochromatic scheme creates a look that’s lunar, particularly during the outdoor mountain parts, and it accentuates the few things in the film that do contain bright color. A red coat Mitchum wears pops out from the screen at the viewer, and so do the blue matches he lights to save himself at one point from freezing to death.

John Wayne’s production company produced Track of the Cat, but this is a Western as far from the world of a typical Wayne film as possible. It’s a West where familial sickness rules and there’s obsessive talk about a monster—the panther—that we hear growling but never see. Did Wellman draw upon Val Lewton’s Cat People and The Leopard Man for inspiration? Whatever the thinking, cinematographer William Clothier and scriptwriter A.I. Bezzerides set out to make a truly different Western with this movie, and there’s no question they succeeded in their aim.

Day of the Outlaw (1959)

Directed by Andre de Toth, Day of the Outlaw is a fascinating exercise in moral ambiguity. The first lines of the film between rancher Blaise Starrett (Robert Ryan) and his foreman Dan (Nehemiah Persoff ) reveal the plot’s mainspring: Starrett can’t stand that farmer Hal Crane plans to build a fence on his own land. Crane is doing something legal, but this fence will limit the range Starrett’s livestock have to roam.

Crane is one of the five or six homesteaders Starrett is at odds with. While he and Dan battled for years against the cutthroats and riffraff who used to populate their stark town of Bitters, Wyoming, making it a safe place, these new arrivals from the East—soft and fat as Starrett sees them—have come to the area with a sense of entitlement and superiority he loathes.

To complicate matters, Starrett once had a romance with Crane’s wife, the attractive Helen (Tina Louise of Gilligan’s Island fame), and he regrets that he did not marry her when he had the chance. He passed on that opportunity, and now she loves her husband. Neither Starrett nor Crane will back down over the land issue, despite Helen’s attempts to prevent violence, and it appears that someone is going to have to die.

This is all taking place in the dead of winter, as a storm is said to be brewing. Inside the saloon, when it’s clear talk has failed, a shoot-out is about to erupt. Men stand poised with their guns ready, waiting for a bottle rolled down the bar to hit the floor. When that bottle shatters, the bullets will fly … except that a surprise occurs—marvelously choreographed by de Toth—and changes the story’s entire direction.

De Toth's film is considered a major influence on The Hateful Eight. Indeed, the whole plot twist that bends the story, taking it to an unexpected place, feels like something Tarantino might have dreamed up. Into the ranchers’ and homesteaders’ world comes a band of menacing outlaws led by a former Army captain (Burl Ives), and the way the criminals act brings out qualities in the other characters the viewer didn’t think they had. The line between nominal villain and nominal hero proves to be a thin one.

Day of the Outlaw is tense from start to finish. Filmed in Oregon in the winter, it presents a snow-clad landscape that’s both harsh and beautiful. Robert Ryan brings his usual strength and ferocity to the film, and Burl Ives excels as the articulate, intelligent military man who may once have been responsible for a civilian massacre. He’s always disciplined and calm, ruling his pack of miscreants with an iron fist, but that he’s capable of cruelty is never in doubt.

The interplay between his character and Ryan’s—neither a total good or bad guy, each displaying respect for the other—recalls the interplay between Richard Boone and Randolph Scott in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T. And, like with Boetticher’s film, the complexity in Day of the Outlaw helps it stand up well today.

Philip Yordan wrote the script, adapted from a novel by Lee Wells, and in a career filled with topnotch work (Detective Story, The Big Combo, The Fall of the Roman Empire), he considered this screenplay among his finest. The story resolves in the treacherous mountains outside the town, but the feeling of victory for the main character is a muted one. After all the dangers and confrontations, work awaits. Now it’s time to get back to running a ranch.

Day of the Outlaw is a strong Western that gets a lot done during its 92-minute playing time.

The Great Silence (1968)

Partly inspired by Day of the Outlaw and a definite influence on The Hateful Eight, Sergio Corbucci’s The Great Silence is an Italian film that ranks among the bleakest Westerns ever made. It takes place in Utah during the Great Blizzard of 1899, and its hero is a mute gunman named Silence.

Played by French actor Jean-Louis Trintignant, Silence takes jobs hunting down bounty killers. The killers have been persecuting a scraggly collection of alleged outlaws who hover outside the hardscrabble town of Snow Hill. It’s clear that the outlaws, who consist of men and women, are ordinary folk driven to stealing because of the brutal winter. Bony in their hunger and dressed in ragged layers, they don’t have the weaponry to be a genuine threat. But the thing is, what the bounty killers have been doing to them is legal, and they are trying to shoot as many of these poor souls as they can before a statewide amnesty law for the thieves is passed and the killers’ source of income dries up.

On the killers’ side, indeed behind them, is Snow Hill’s richest citizen, Pollicut, a man who owns a store, runs the bank, and also functions as the town’s justice of the peace. He is thoroughly corrupt, and we learn that he was the one—years ago, when Silence was a child—who had Silence’s parents killed and the boy’s vocal chords cut. Though Silence later caught up with him and shot off his right thumb, Pollicut has not improved his behavior. He’s now someone who would have a husband murdered just so he can try having at the man’s wife.

Best known for directing the original Django (1966), Sergio Corbucci directed 13 Westerns during his career. Several reflected his social and political concerns. But while the others—including his Mexican Revolution-set films, The Mercenary and Companeros—were filmed in the Almerian desert of Spain (as most Spaghetti Westerns were), The Great Silence was shot in the Italian Dolomites.

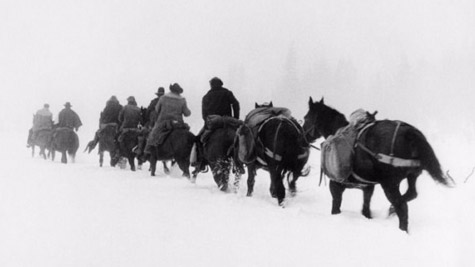

The mountain location sets the movie apart from nearly all other Italian Westerns, and despite the downbeat thrust of the story, there’s a grandeur to the way the movie is filmed, with spectacular shots of isolated figures moving through vast white spaces. Snow blankets everything here—and everyone—throughout the film, looking cold and uncomfortable. Helped by Ennio Morricone’s score—the soundtrack is haunting, even sad—The Great Silence paints a picture of a remarkably vicious world. The people living in it seem to exist in an endless winter, where daylight doesn’t last long, amenities are rare, and power belongs to greedy thugs.

Klaus Kinski plays the head thug, called Loco, and it’s a measure of the darkness Corbucci was going for that he cast Kinski because of his resemblance to the vampire character Boris Karloff plays in Mario Bava’s horror film Black Sabbath. Kinski (who did a number of Italian Westerns) is perfect in the role, and if there’s strong tension between his character and the sheriff character played by Frank Wolff, it could be because that tension was real.

According to an interview Corbucci did years later, Kinski went up to Wolff before shooting started and told him: “I don’t want to work with a filthy Jew like you; I’m German and hate Jews.” Wolff tried to strangle Kinski, and people on the set had to jump in. For the rest of the time filming, Wolff wouldn’t say a word to Kinski unless he had to for the script. Kinski would eventually say that he offended Wolff to make Wolff hate him, as the sheriff is supposed to in the movie.

The Great Silence performed adequately at the European box office, and it did not get a release in the United States. There’s no question its downbeat nature and pessimistic ending contributed to its reception. Corbucci’s late ‘60s anger—an anger coming in the wake of Che Guevera’s and Malcom X’s deaths—serves as the movie’s fuel, and indeed the film functions as a commentary on the futility of opposing the interests of the moneyed and powerful. Everyone halfway decent, from the sheriff to Silence to the strong woman Vonetta McKee plays, is destroyed, and only the vile survive.

It’s a film that would come to be appreciated in subsequent years, and it now rates in the very top tier of the non-Sergio Leone Spaghetti Westerns. It’s hard to believe that Robert Altman didn’t see the film before making McCabe and Mrs. Miller three years later or that Clint Eastwood didn’t give it serious study before making Unforgiven. The Great Silence is an anti-Western par excellence.

McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971)

Though it has a sterling reputation now, McCabe and Mrs. Miller received mixed reviews when it opened. No wonder; even by early 1970’s standards, it must have seemed an odd film, with its elegiac Leonard Cohen songs, overlapping soundtracks, and faded soft-focus look. Not to mention that, from first frame to last, it subverts Western tropes.

There is a mysterious solitary man who arrives in town like in classic Westerns, but this guy—despite having a “rep,” as one character says—is no gunslinger. Does he have a Swedish gun? Did people once call him (Warren Beatty no less) Pudgy McCabe?

Frontier prostitute characters are nothing new, but there’s never been one quite like Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie), who has a head for business and an instinct for survival far sharper than McCabe’s. In this movie, it’s the woman who approaches the man with a moneymaking proposal, and thereafter—though he spends the cash to erect their brothel and pays for everything in their enterprise—she runs the daily operations. We keep seeing McCabe knocking on her door, asking permission to enter her room, and even when they are about to sleep together, she indicates that he has to leave money on her dresser for the privilege like a regular paying customer.

Where The Great Silence shows people using the state’s authority to commit terrible acts and profit from them, McCabe and Mrs. Miller undercuts the sacrosanct American notion of individual business initiative being the engine that drove the country’s expansion. What are essentially corporate forces intimidate and crush the little guy, the freewheeling capitalistic dreamer.

As an entrepreneur, the person who took risks and built something from nothing, you get one chance to surrender your business once you are approached by the larger players. You get a single friendly offer to sell to them. If you don’t accept the terms offered, woe be unto you; try as you might, you cannot ask for reconsideration, and recourse to the law will get you nowhere. Bravado and naivety in the face of these forces only lead to defeat. And all this happens in a mud hole of a town populated by people who gossip and chatter and tell tales incessantly. The American frontier, as depicted in the film, has seldom looked so unglamorous.

The snow in the movie arrived with the timing of a miracle. During production, the climactic shoot-out was the final sequence actually shot. The sequence called for snow, but they had none where they were filming in Vancouver, Canada. That day, as shooting on the sequence began, Robert Altman had the set hosed down to give everything a wintry appearance. Fortunately, after lunch, snowfall hit.

What you see as McCabe fights for his life against the three hired gunmen is heavy snow coming down on the actors. It all adds to the sense of realism the gunfight has—a gunfight unlike any other in a Western. There is no heroism—nothing of the drama of a High Noon-style finale—nor is there a Wild Bunch-type catharsis achieved. Besides Mrs. Miller, nobody in the town seems to know that McCabe is engaged in a fight for his life—the villagers are intent on saving their burning church. Considering how things finish for McCabe and how alone he is at the end, the snow somehow adds to the film’s poignancy.

The ultimate shot of John McCabe—in a sitting position, covered in snow, not moving as the snow swirls around him—is a shot you can’t forget. McCabe and Mrs. Miller is a masterpiece and Robert Altman’s best film (which is saying something), and it is the warmest and most humane and affecting of all the wintry Westerns.

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. He co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His most recent novel is the psychological thriller Graveyard Love, available from Broken River Books.