The plot is elegant in its simplicity: on the day he marries a young Quaker woman and retires his badge, Will Kane, the marshal of a dusty little town in the middle of nowhere, learns that a man named Frank Miller is arriving on the noonday train to kill him. Three of Miller’s hoods are waiting at the depot, but when Kane turns to his fellow townspeople for help he is rejected by the citizens, abandoned to his fate in a shootout with four vengeful gunmen.

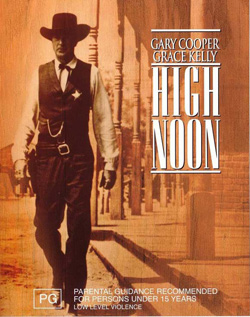

The film was a smash hit upon its release and won four Oscars at the Academy Awards. It reinvigorated the career of its aging star Gary Cooper (who reestablished himself as a box office draw and won a Best Actor statue), produced a hit song (“High Noon” by Tex Ritter), and help inspire a new slate of so-called “adult” Westerns.

High Noon holds up remarkably well. Foreman’s script is not so much critical of America as it is suspicious of the fault lines intrinsic in democracy. This potent critique is played out in the middle passages of the film as Kane, to paraphrase the Hawksian criticism, runs around town begging for help. Hawks, like certain other detractors, misrepresented the character of the townspeople in these scenes, attributing their lack of assistance to cowardice. While it is true that many people in the film are afraid (character actor Harry Morgan has a memorable scene as a town leader who forces his wife to lie about his whereabouts as he cowers in the kitchen), it is essential to note that the citizens of Hadleyville are not monolithic. Some, like Morgan, are scared. Others, like the snide hotel clerk and the sleazy saloon owner, resent Kane for cleaning up the town and running off lucrative business. Kane’s deputy, played by Lloyd Bridges, bolts because he’s angry that Kane didn’t nominate him to become the new marshal. And on and on. It should also be pointed out that some people—a friendly family man, an eager teenager, the town drunk—do volunteer help, only to be turned down or released of their obligation by Kane.

The point of High Noon isn’t that the people of the town are cowards. The point is that human beings are subject to many different forces—fear, self-interest, jealousy, stupidity—that slow down the process of doing the right thing. “People,” one crusty old-timer tells Kane “gotta talk themselves into law and order.”

There’s a fascinating scene early in the film when a judge played by Otto Kruger gives Kane a history lesson, a lesson he dispenses as he’s folding up an American flag and throwing lawbooks in a satchel:

In the 5th century B.C., the citizens of Athens, having suffered grievously under a tyrant, managed to depose and banish him. However when he returned some years later, with an army of mercenaries, those same citizens not only opened the gates for him but stood by while he executed members of the elected government. A similar thing happened about eight years ago in a town called Indian Falls. I escaped death there only through the intercession of a lady of somewhat dubious reputation—at the cost of a very handsome ring which once belonged to my mother. Unfortunately, I have no more rings.

This historical context helps establish the film’s narrative as the dramatization of a cautionary tale, one that could happen anywhere—even, Foremen seemed to be saying, in modern day America. This tale is un-American only if you think Americans are somehow immune to human nature.

Of course, the film itself has to function as a drama before it can be put to any real use as an allegory. In this respect, High Noon is untouchable. Floyd Crosby’s stark cinematography emphasizes empty skies dusty streets. Dmitri Tiomkin’s score is spare, built around the title ballad that gives the whole work the feel of an elegy. And the cast is superb, from top to bottom, filled out with rising stars like Grace Kelly and Katy Jurado, and stocked with leathery character actors like Richard Wilke and Lon Chaney.

Of course, the film itself has to function as a drama before it can be put to any real use as an allegory. In this respect, High Noon is untouchable. Floyd Crosby’s stark cinematography emphasizes empty skies dusty streets. Dmitri Tiomkin’s score is spare, built around the title ballad that gives the whole work the feel of an elegy. And the cast is superb, from top to bottom, filled out with rising stars like Grace Kelly and Katy Jurado, and stocked with leathery character actors like Richard Wilke and Lon Chaney.

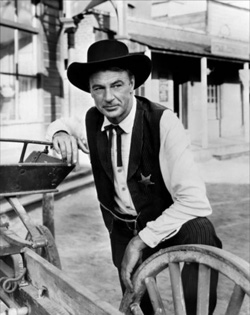

And at the center of it all is the legendary performance by Gary Cooper. In 1952, he’d been riding the range longer and to greater success than any other actor (even John Wayne). By ‘52, Coop was, in many ways, the quintessential American star. Oddly enough, though, we rarely watch the action movies and heroic westerns that made him a household name in the thirties and forties. Instead, it is his late career work (dark, complicated films like Man Of The West and The Hanging Tree) that make him a potent symbol to us today.

He was, in some ways, the anti-Wayne. Unlike Wayne, Cooper didn’t become more an authoritarian as he aged onscreen; he seemed to grow, if anything, more insecure. High Noon utilizes the accumulated weight of Cooper’s screen persona—two decades of being the stalwart image of American manhood—but it transcends it at the same time by taking that tall, handsome hero of the west and putting years on his face and stiffness in his walk. Gone is the golden beauty of his youth. Now there’s worry clouding his eyes, the burden of hard-won wisdom. Sure, he goes to his friends looking for help when the killers are coming. Who, outside of a comic book hero, wouldn’t? That humanity doesn’t diminish his heroism. It makes his heroism more palpable and real. Gary Cooper never had a finer moment than when he gathers his final courage and fortitude and heads out into the blinding noonday sun to negotiate his fate with a six-shooter. The moment is mythic and human all at once, much like High Noon itself.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of Hell on Church Street.

Thanks so much for this post! I was about 6 or 7 when I saw this movie for the first time, and as a kid, I found the action to be slow, (except for the Henry Morgan scene which all the kids think is hysterical.) For each future viewing I was a couple of years older and understood more of the fine points that you describe in this excellent post. As your reward, I will sing to you my favorite part of the song: “For I must face a man who hates me Or die a coward, a craven coward, Or die a coward in my grave .” Thanks again. Terrie