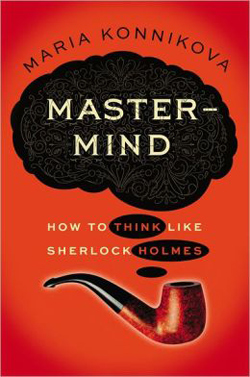

Maria Konnikova’s Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes is an examination of the mind and methods of the great detective and a discussion of how current techniques in neurology and psychology can help you become more of a master detective in your own life (available January 3, 2013).

Maria Konnikova’s Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes is an examination of the mind and methods of the great detective and a discussion of how current techniques in neurology and psychology can help you become more of a master detective in your own life (available January 3, 2013).

Journalist Maria Konnikova writes Scientific American’s “Literally Psyched” column. Mastermind is her first book.

Maria Konnikova was raised on the stories of Sherlock Holmes. Whether or not this early introduction to the world’s brainiest detective influenced her vocation, it certainly helped give birth to Mastermind, a book that presents Holmes in his natural role as a mentor of mindfulness. In writing it, she aims to help readers develop habits of thought that will allow us to improve our intellectual and creative capacity and engage mindfully with ourselves and the world.

The book gives the average person (that is, the average motivated person—the task is not an easy one) a boost onto the Holmesian playing field. Konnikova uses the character of Holmes not just to entertain, but because Holmes himself, by revealing his deductive process to his friend Watson in story after story, “provides an education in improving our faculty of mindful thought and in using it in order to accomplish more, think better, and decide more optimally.”

In picking up this book I was sort of hoping for a step-by-step approach. But it’s not a how-to book, nor is it a detective manual. Instead it’s a challenge to readers to take up rigorous brain retraining and approach our lives with engagement and penetrating awareness.

Mastermind’s launch is timely. We bemoan the state of our educational system. We multitask constantly and fail to do anything particularly well. We wish we were smarter, more creative. We want to make better decisions, keep up with a world racing away from us, and hang onto our sanity. We glimpse the spectre of cognitive decline and are willing to do just about anything to prevent it. We take brain-healthy exercise and eat brain-healthy food. The least spiritual among us now practice brain-healthy mindfulness meditation. We’re primed for Mastermind.

Konnikova breaks explanations of Holmes’s seemingly superhuman deductive powers into essential building blocks. I, for one, did not grasp all it presented in a single reading. I wish, in fact, she would offer a course. But by illustrating tenets of cognitive science using Holmes’s own words, she shows us what’s necessary to develop his powers of disciplined mindfulness (in contrast to passive mindlessness); selective observation (in contrast to sight alone); inspired hypothesis; and reasoned deduction. The recipe requires self knowledge, imagination, the exclusion of assumptions based on extraneous prior experience, and conclusions drawn exclusively from that which is observed.

On the subject of distancing through mental techniques that foster focus and creativity, the author says:

Let’s return for a moment to a scene that we’ve visited once before, in The Hound of the Baskervilles. After Dr. Mortimer’s initial visit, Dr. Watson leaves Baker Street to go to his club. Holmes, however, remains seated in his armchair, which is where Watson finds him when he returns to the flat around nine o’clock in the evening. Has Holmes been a fixture there all day? Watson inquires. “On the contrary,” responds Holmes. “I have been to Devonshire.” Watson doesn’t miss a beat. “In spirit?” he asks. “Exactly,” responds the detective.

What is it, exactly, that Holmes does as he sits in his chair, his mind far away from the physicality of the moment? What happens in his brain—and why is it such an effective tool of the imagination, such an important element of his thought process that he hardly ever abandons it? Holmes’s mental journeying goes by many names, but most commonly it is called meditation.

When I say meditation, the images invoked for most people will include monks or yogis or some other spiritual-sounding monikers. But that is only a tiny portion of what the word means. Holmes is neither monk nor yoga practitioner, but he understands what meditation, in its essence, actually is—a simple mental exercise to clear your mind. Meditation is nothing more than the quiet distance that you need for integrative, imaginative, observant, and mindful thought. It is the ability to create distance, in both time and space, between you and all of the problems you are trying to tackle, in your mind alone. It doesn’t even have to be, as people often assume, a way of experiencing nothing; directed meditation can take you toward some specific goal or destination (like Devonshire), as long as your mind is clear of every other distraction—or, to be more precise, as long as your mind clears itself of every distraction and continues to do so as the distractions continue to arise (as they inevitably will).

The book is peppered with deliciously quirky puzzles that demonstrate just how lazy a brain can be and how fast it makes assumptions and jumps to Watsonian conclusions. I found myself refusing the correct answers, recognizing the error of my approach only after examining and re-examining my logic. In some cases the problem stems from the brain’s knee-jerk responses, the shortcuts of mindless habit. But even when habits have worn grooves in our brains, we close the book’s pages with a methodology for rocking free of those ruts; a goal we’ll achieve if we practice, practice, practice.

Is there a group more motivated to improve our minds than those of us who, behind laughter over our shared and increasing cognitive dysfunction, uneasily wonder whether we’ll manage to stay connected to this fast-paced world throughout our remaining decades? Whether the crossword puzzles, Sudoku, and Lumosity games to which many of us devote time and attention will sufficiently hone our mental powers?

“If you get only one thing out of this book,” Konnikova says, “it should be this: the most powerful mind is the quiet mind. It is the mind that is present, reflective, mindful of its thoughts and its state. It doesn’t often multitask, and when it does, it does so with a purpose.”

What a relief to be told to calm and control our minds, applying them to one task at a time.

See our full coverage of new releases with our Fresh Meat series.

For more information, or to buy a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Lois Karlin writes fiction and blogs at Women of Mystery. In the pursuit of authenticity she’s learned to dag sheep and take down a silo, and knows where to deep six a body in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Thanks Lois. This looks like a really interesting book.

Fascinating. Especially as my brain becomes a little more fried each year.

It is a really good book! I hope that all modern writers will take an example from this one. I have described it at this article and I want to share it with all my friends and good people. I hope that you will like it as many users in the web!