“What is a ghost?” It’s the question at the heart of Guillermo del Toro’s near-perfect The Devil’s Backbone, the pin that holds together the interwoven threads of his layered story. Is it a literal ghost: a restless spirit that persists in stalking the halls at night? Or perhaps the looming specter of war, in a place full of orphans whose parents were claimed by the conflict… Or is a ghost simply the lingering regret for words unsaid, chances untaken, dreams unfulfilled?

The story opens at a remote orphanage in the final days of the Spanish Civil War. Young Carlos (Fernando Tielve) arrives with a suitcase and shoebox of childish treasures, confused and uncertain. And for all that the teachers—including the eloquent Dr. Casares (del Toro fave Federico Luppi) and the elegant Carmen (Marisa Paredes)—are kindly, Carlos has a hard time settling in. The resident bully Jaime immediately dislikes him, the orphanage echoes eerily with secrets, and there is an unsolved mystery surrounding a boy who abruptly disappeared the night a bomb fell in the courtyard.

When Carlos is given the boy’s bed, he soon suspects that the missing Santi never actually left the orphanage. Something began haunting the school in the wake of his disappearance, a being the other boys call “The One Who Sighs”, and it isn’t long before Carlos comes face to face with the ghost and hears a most frightening warning: “Many of you will die.”

Meanwhile, the caretaker Jacinto (Eduardo Noriega) has grown impatient. He’s convinced Carmen and Casares have been working with the Reds and are hiding gold. A former inmate of the orphanage and hiding to avoid the war, Jacinto has dreams of wealth and grandeur. Terribly unhappy with his lot in life, he refuses to let anything stand in the way of those dreams.

What unfolds is a story that is both brutal and beautiful, supernatural and utterly human, in a way only del Toro can balance. Told primarily through the eyes of the orphans, it’s a boy’s coming of age in a time and place so turbulent that ghosts are unavoidable and innocence is fragile.

Stylistically speaking, this may be the most beautiful ghost story ever filmed. The saturated color palette is one of contrasts: deep blues and grays against yellows and oranges. The cloudless pale sky is vast over the golden grass and the huge orphanage is now mostly empty and dilapidated, emphasizing the sense that this is a place abandoned and forgotten by the outside world. The characters are often divided by space—both mental and literal—and cannot escape their situation.

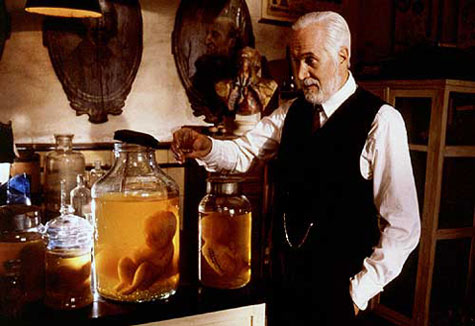

The cinematography adds to the alternating loneliness and claustrophobia, the camera is at times drawn back to frame the characters as tiny insects, while other times it is drawn in for uncomfortable close-ups. Death and war are ever-present in the vivid symbols and trappings of the orphanage: the unexploded bomb lodged in the courtyard and Carmen’s wooden leg, the safe full of gold Jacinto is so desperate to unlock, bleeding crucifixes and Casares’ jars of preserved malformed fetuses (which provide the film’s title).

And then there’s “The One Who Sighs” himself, a ghost unlikely any other. With a cloud of blood floating above the flaking crack in his head, his bones illuminated as if x-rayed photographs, he is both horrifying and tragic. A broken porcelain doll, like a fly trapped in amber, he is caught forever in the moment of his death. As with many of del Toro’s monsters, he is also not the threat he seems; debts may be owed to the dead but they will only collect their due.

Even with such stunning visuals, a ghost story such as this would fall apart without powerful performances. Luckily the cast rises to the challenge, particularly the untested child actors. Fernando Tielve as Carlos provides the courageous heart while Eduardo Noriega plays Jacinto as a fire-eaten and greedy man too often spurned and soured by it. Luppi is yet again compelling, conveying rage, disappointment, and heartache with equal conviction and Marisa Paredes’ Carmen is the embodiment of regret and weary disillusionment.

This being a del Toro picture, there’s an unflinching commitment to fully showing the tolls of war. Men are executed, children die, and unforgivable cruelty is at every turn. Jacinto himself gives voice to the truth: in such barbaric times people expect and even ignore further atrocities. At some point the world stops caring.

But del Toro also refuses to condone this nihilism. Even with so much death and shameful waste there will always be hope. The human spirit is something that cannot be daunted forever; eventually wars must end and people must rebuild. The future depends upon the next generation—and so it is the duty of the children to persevere and keep hope alive—to right the wrongs of their elders and seek justice before walking away from the past and beginning anew.

It’s impossible for me to be impartial about this movie. It is, in my opinion, del Toro’s masterpiece and is best paired with its follow-up, Pan’s Labyrinth, which del Toro made as the second half of a set. The Devil’s Backbone succeeds on every level: as an elegy on war, as a ghost and horror story, as a tale of a boy’s coming of age, and as a commentary on the nature of regret and the power of the human spirit. Moving, heart-breaking, terrifying, thought-provoking—it’s guaranteed to take you through the whole gamut of emotion.

It’s impossible for me to be impartial about this movie. It is, in my opinion, del Toro’s masterpiece and is best paired with its follow-up, Pan’s Labyrinth, which del Toro made as the second half of a set. The Devil’s Backbone succeeds on every level: as an elegy on war, as a ghost and horror story, as a tale of a boy’s coming of age, and as a commentary on the nature of regret and the power of the human spirit. Moving, heart-breaking, terrifying, thought-provoking—it’s guaranteed to take you through the whole gamut of emotion.

In interviews, Guillermo del Toro often cites this as his favorite and most personal film. He drew upon personal experiences, childhood nightmares, and a deep connection with history to craft this phantasmagoria. His passion and bond with the story is tangible in every scene. Just as “The One Who Sighs” cannot rest until his demands are met, this is a story that demands to be felt. And regardless of how you watch it—in the bright light of day or in the atmospheric darkness of night—The Devil’s Backbone will linger…

Just as the greatest campfire ghost stories do.

Angie Barry wrote her thesis on the socio-political commentary in zombie films. Meeting George Romero is high on her bucket list, and she has spent hours putting together her zombie apocalypse survival plan. She also writes horror and fantasy in her spare time, and watches far too much Doctor Who. You can find her at Livejournal.com under the handle “zombres.”

Read all posts by Angie Barry at Criminal Element.

This is my favorite Del Toro film as well, although I detect his hand in The Orphanage, which he produced. If you want a triple bill some spooky evening, that would make a wonderful third.

What I like most about the man’s films is that always the monsters may well be the scariest part of the film, but the real monsters are always the human ones. Monsters are Del Toro’s middle ground. Humans are both the light and the dark in his cinematic world. Every Del Toro film, or a least every one that I’ve seen, follows this pattern. Substituting the vampires for humans in Blade II, the same pattern emerges–the monsters are the victims while the real evil resides in the “humans.”