For a movie that has accumulated such a high volume of accolades since its premiere, it’s a bit perplexing to find that Baby Driver is actually a bit of a difficult movie to review. Perhaps it’s because so much has been said about the film already, but the more likely reason is that the movie can be considered a sort of a self-review.

A pop-culture pastiche that uses an abundance of tropes, pop-culture references, and singular craft, Edgar Wright’s fifth film is a bit of a tongue-in-cheek assessment of the film industry’s current status quo while also being a radiant beacon of creativity. Whether this was a conscious decision on Wright’s part or not remains murky, but it certainly entices my mind the more I think about the possibility of Baby Driver being a deceptive film essay. That said, here goes my review anyway. Perhaps the best way to start is by addressing the man in the director’s chair.

The 43-year-old Edgar Wright’s career trajectory has actually followed a pattern that matches that of other talented directors—meaning that upon breaking into the mainstream, he’s had his studio clashes. After concluding his seminal Blood and Ice Cream trilogy (Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and World’s End) in 2013, Wright was then attached to direct Ant-Man for Marvel, a project he had been writing a script for with Joe Cornish since 2006. Unfortunately, he faced creative differences with Marvel and ultimately abandoned the project in 2014. (He’s even gone on to say that he refuses to watch the released feature—not even the trailer—even though he still holds a screenwriting credit on the picture.)

While it would have been enticing to see Wright apply his vision to the uber-popular superhero movie craze (something he admittedly hinted at in Scott Pilgrim Versus the World), his talents were instead utilized on personal projects. For that reason, we should be extremely grateful that he was immediately given the chance to pursue a passion piece of his after walking away from Marvel.

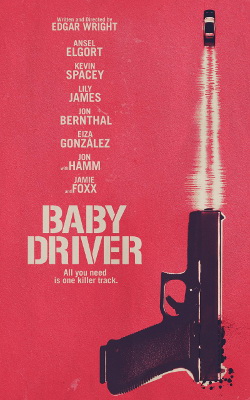

Originally conceived of back in 1994 (a time when Wright was probably shooting his lightly-watched, shoe-string budgeted debut film, A Fistful of Fingers), Baby Driver focuses on the title character (Ansel Elgort), a young, Atlanta-based getaway driver who blocks out his tinnitus by constantly listening to music. Surviving a car crash that took the lives of his parents, Baby found himself coming into a life of crime at a young age, leading him to the enigmatic criminal mastermind Doc (Kevin Spacey). Finding himself in huge debt to Doc, Baby is brought on as a getaway driver to aid in bank-heist jobs that Doc organizes with a revolving crew of criminals.

It’s apparent, however, that the mild-mannered and courteous Baby is very distant from the criminal element. So when he finds a love interest in Debora (Lily James), he immediately decides to leave his life of crime behind. Of course, that isn’t so easy…

While essentially a throwback picture to chase/heist films of yesteryear (like Bullitt), the film finds character in how contemporary it is as well. Perhaps more than any other director since Quentin Tarantino, Edgar Wright is able to present viewers with a world that feels anachronistic at times but is completely derived from his ethos and feels fully palpable.

Palpable pulp fiction at that, I might add, which is principally exampled in the protagonist, who is one of the most interesting millennials I know. The ear-bud wearing, quick-footed Baby has a taste in music that is a bit more retrospective than his age would suggest, but that doesn’t dilute the fact that he has a whole selection of iPods on his person or that much of his dialogue is taken from something he’s seen on TV. Which, of course, leads to the film’s strongest card: its pulsing soundtrack.

Wright has constructed his film to have the fluidity and synchronicity of a music video (unsurprisingly, Edgar Wright had previously used a scene he intended for Baby Driver’s opening in the music video he directed for Mint Royale’s “Blue Song,” which has a brief appearance in the film), and the scenes possess a momentum to them that’s singular to Wright’s craft.

Anyone that has seen an Edgar Wright film can attest that he’s a valuable asset for contemporary cinema, as he often approaches his films with the maturity and visual splendor of a Danny Boyle picture while still retaining a boyish appeal towards schlock and style. In Baby Driver, however, he finally has the means to give us some truly stellar set-pieces that correlate with his penchant for music and occasional bloody action. The scenes are edited in a way that coincides with the film’s music-based pathos, and at times, Baby Driver’s action scenes remarkably recall the work of anime director Shinichirō Watanabe—particularly his masterpiece, Cowboy Bebop.

Still, with all this attention to spectacle, Baby Driver doesn’t (entirely) come off as a style-over-substance affair, primarily because of its well-developed characters. Ansel Elgort, with his lovable southern accent and reserved character, makes for the summer’s most affable action hero, and the script makes use of every scene he’s in to let us know what kind of person Baby truly is.

Kevin Spacey also gives another impressive villain turn here. While Doc is certainly evil, his sense of humor and fatherly-moments make him very watchable, and he never comes off as mean-spirited. Other smart casting choices (CJ Jones as Baby’s deaf and handicapped foster father, Jamie Foxx as a reckless thug, and Jon Hamm as the film’s ultimate big-bad) round out the film well and suggest that Edgar Wright might be ready to do an ensemble picture in the vein of Paul Thomas Anderson or Robert Altman.

As riveting a cinematic experience that Baby Driver is, however, it does have its flaws. For one, the romantic portions of the film don’t feel quite as natural as the rest of the picture does, and the chemistry between Ansel Elgort and Lily James is a little questionable. While Lily James is often charming in her parts, the British actress isn’t as memorable in the film as the rest of the cast. It’s unclear if that’s on her or Wright for underwriting her character. Also, while Baby Driver never loses its energy, the last act is more violent and less creative than the previous two. And though the climax is satisfying, it’s also easy to perceive as bombastic.

All in all, Baby Driver is certain to be one of the most propulsive and gratifying mainstream films you’ll see all year, and it’s another case for why Edgar Wright is one of the best working directors. General moviegoers and cinephiles alike will find a lot to love in Baby Driver, and its meticulous structure and wealth of ideas may even warrant repeated viewings.

The only frustrating thing about the film is the thought that Wright may have peaked with this movie, as Baby Driver is so tightly presented and rich in passionate, idiosyncratic content that it’s difficult to think that Wright will be able to give us another picture that’s equally impressive (think about it, has Christopher Nolan really put out another great movie since The Dark Knight?).

Still, it’s hard to fault a movie for being too fucking good, and if any director has showcased that he has lasting creative stamina in today’s cinematic landscape, then it would definitely be Edgar Wright.

Watch the trailer for Baby Driver:

Peter Foy is an avid reader and movie buff, constantly in need to engage his already massive pop-culture lexicon.

We mined the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reports for the past six years to distil the data about crimes against women and here’s what we found, in five charts.