Lots of people know about the landmark 1971 British gangland film Get Carter (and if you’re a crime fiction/film enthusiast who doesn’t: stop here, go watch it, then come back and read this later). But too few have been hipped to Ted Lewis, the author of the novel that served as that movie’s basis. Lewis was a noir maverick, the originator of the British school of hardboiled crime fiction. He is the U.K.’s answer to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. David Peace is just one of the legion of contemporary Brit Grit authors who cite him as an influence. He was also a fascinating, if ultimately tragic, guy: a multi-talented man gifted with artistic genius, and a good-looking bloke with the ability to be a great charmer; but also someone with a dark side, who was limited by a debilitating addiction to alcohol.

Lots of people know about the landmark 1971 British gangland film Get Carter (and if you’re a crime fiction/film enthusiast who doesn’t: stop here, go watch it, then come back and read this later). But too few have been hipped to Ted Lewis, the author of the novel that served as that movie’s basis. Lewis was a noir maverick, the originator of the British school of hardboiled crime fiction. He is the U.K.’s answer to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. David Peace is just one of the legion of contemporary Brit Grit authors who cite him as an influence. He was also a fascinating, if ultimately tragic, guy: a multi-talented man gifted with artistic genius, and a good-looking bloke with the ability to be a great charmer; but also someone with a dark side, who was limited by a debilitating addiction to alcohol.

Like Jack Carter, the mob enforcer who is the lead character of Get Carter (Jack’s Return Home is the original name of Lewis’s 1970 novel), Lewis came from the North of England and lived in London as an adult. Growing up in the small town of Barton-Upon-Humber, Lewis showed himself to have an artistic bent from his earliest years. A lifelong visual artist, Lewis was rarely found without his sketchpad through his boyhood years. His cousin Alf remembers a time when their families were together at one of their homes and nobody could find Ted (Edward then). Alf finally discovered his cousin up in an attic, watching a hard rain come down, and intently drawing in his omnipresent pad. Alf asked Edward what he was doing, and got the matter-of-fact response, “Drawing the storm.” The case can be made that drawing the storm is precisely what Lewis the author was up to when writing novels as an adult. Prodded on by an influential grammar school teacher who was a published author, a teenaged Lewis wrote some short stories for the school’s annual magazine; the stories are stunningly good, and surprisingly intense, to have come off the pen of someone that age. Lewis was also a musician who mostly played jazz piano.

After studying commercial art at nearby Hull College of Art (during which time he played piano in a trad jazz band), Lewis went off to London, where he got various jobs drawing for advertising firms. He also did freelance work then, drawing panels for BBC kids’ TV shows and doing illustrations for books, among them editions of The Bridge on the River Kwai and Alice in Wonderland. Lewis also did animation work on The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine movie. All the while he was at work on his debut work of full-length fiction, the clumsily titled autobiographical literary novel All the Way Home and all the Night Through. Published in 1965, when Lewis was 25, the book is weak to the point of being shy-making. Lewis didn’t think so, though, and was crushed when the novel failed to make an impact.

Lewis continued to work as a freelance visual artist after the publication of that first novel. He was still writing, though, one literary project being a serialized story called “Two-Sided Triangle,” that appeared to be a thinly-veiled account of his marriage to a leggy woman he met in London, their wedded life just underway then. Like All the Way Home, the story is agonizingly self-centered and, frankly, embarrassing; it was serialized in the popular fashion/culture magazine Petticoat.

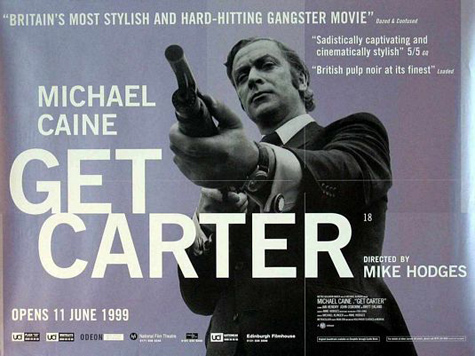

Lewis still wanted to be a novelist, though, and he had resolved to have his next book be something blatantly commercial. A film buff especially taken by American crime movies, a fan of Chandler, and an English citizen aware of his country folk’s current interest in the gangland doings of figures like the Kray and Richardson families (members of the former family were personally known by Lewis), he wrote the revenge-themed crime story Jack’s Return Home—which John Williams has called “the finest British crime novel ever written.” Like the best work of his hero Chandler, the book is both a beautifully written crime novel and so much more. Among other things, JRH is a poignant exploration of the hopelessly complicated relationship between two brothers. Lewis the author had found his voice. MGM snapped up the movie rights before the first copy of the novel landed in a bookseller’s stall. The 1971 film, directed by then up-and-coming auteur Mike Hodges and starring Michael Caine in a performance that is best described as explosive, the movie was an instant classic and today holds a high place on the British Film Institute’s list of best British films of all time. Lewis the movie fanatic was thrilled about the film, and wanted so badly to be involved in its making that he offered his input on the screenplay free of charge, but his services were turned down by the principals.

Of the people who do know something about Lewis’s literary work, many of them are only aware of JRH. But Lewis wrote seven more books before his early death at age 42. And while his remaining oeuvre is uneven, some of his titles are stellar works of noir, one is an excellent literary novel, and his last book is a staggering work and one of the great overlooked classics not just of crime fiction but of fiction, period.

Plender (1971) is a bitingly sinister story about two boyhood rivals who meet up by chance in their adult lives; the guy who got the worst of things when they were younger initiates a set of interactions that threatens to imperil them both. Billy Rags (1973) is a bracing prison novel based on the diaries of noted criminal John McVicar, and Jack Carter’s Law (1974) is, like the first Carter novel, a convincing portrait of England’s criminal underworld. While these three don’t have the psychological depth that makes JRH such a life changer, they are all finely written works of edgy crime fiction that stand up to some of the best examples in the genre. (Sidenote that will be of interest to any Lewis buff: in 1973 a standalone Carter short story of Lewis’s appeared in an English porn mag).

From there, Lewis returned to the literary fiction milieu with 1975’s The Rabbit, a coming-of-age novel that was similar to, but worlds better than, his debut. Done in the vein of gritty Brit kitchen sink dramas like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Room at the Top, This Sporting Life, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, etc., The Rabbit concerns a sensitive art student who spends a summer toiling at the rock quarry his father manages. It’s extremely well written. What followed, however, were Lewis’s two weakest crime novels. His word-for-word writing craftsmanship in both these books is faultless, and both contain the almost-unbearable intensity to be found in all his crime stories, but these two are flawed in ways that leave them rungs lower in quality level than the other titles in his personal canon. Boldt (1976) is set in America, where Lewis had never been, and is just plain nasty. Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon (1977)—via which a final stab was made at using his most famous character to try and garner some sales that were sorely lacking from his recent works—contains some of Lewis’s best stinging humor, but is a forgettable read in the end.

After that run of titles, Lewis’s longtime publisher Michael Joseph was done with him. His marriage had collapsed and while his ex-wife and their two daughters continued to live in the South of England—where Lewis the would-be family man once aspired to make of himself a country gentleman—he was back home in Barton-Upon-Humber, living with his mum and making a nuisance of himself at the local pubs and around town. A handsome devil who could turn on the charm when he cared to, Lewis was involved in romantic entanglements—sometimes with married women—to his dying day. An opportunity to bring some life back into his writing career materialized when he was commissioned to author a multi-part script for the popular TV show Doctor Who; but Lewis’s text didn’t resonate with the show’s brass, and the episodes were never made.

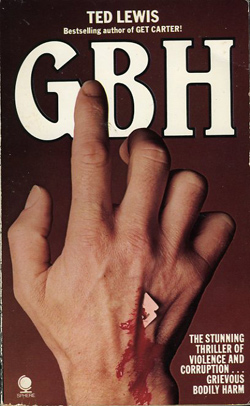

But this is where Lewis’s story gets the most interesting. Because just when he seemed to be at the end of the line, both as a writer and a human being, he pulled out all the stops and wrote his life’s great work. GBH, published in 1980 as a paperback original and utterly ignored by critics and the book-buying public alike, is both an astonishingly effective crime novel and a tour-de-force of alienation literature. Leaving it all on the page, Lewis (whom one lifelong friend has called a “dark angel,” and who was known to suffer from bouts of depression) emptied out his tormented soul by way of telling the nightmare tale of George Fowler: a once-powerful crime lord who has had the rug taken out from under him and whose many enemies appear to be working in unison to corner him into a personal Hell. GBH is hallucinatory, it’s frightening, it’s can’t-put-it-down suspenseful and an absolute brainfuck. It has Lewis’s most fully developed female characters, including one of the more intriguingly enigmatic figures to ever appear in the pages of a novel. To John Williams’s claim about Jack’s Return Home being the finest British crime novel, I say Williams got the right author but the wrong title. In discussing Lewis and in focusing on GBH specifically, Derek Raymond wrote, “GBH is a novel as direct as it is stunning,” and “he is an example of how dangerous writing can really be when it is done properly, and Ted Lewis’s writing proves that he never ran away from the page.”

But this is where Lewis’s story gets the most interesting. Because just when he seemed to be at the end of the line, both as a writer and a human being, he pulled out all the stops and wrote his life’s great work. GBH, published in 1980 as a paperback original and utterly ignored by critics and the book-buying public alike, is both an astonishingly effective crime novel and a tour-de-force of alienation literature. Leaving it all on the page, Lewis (whom one lifelong friend has called a “dark angel,” and who was known to suffer from bouts of depression) emptied out his tormented soul by way of telling the nightmare tale of George Fowler: a once-powerful crime lord who has had the rug taken out from under him and whose many enemies appear to be working in unison to corner him into a personal Hell. GBH is hallucinatory, it’s frightening, it’s can’t-put-it-down suspenseful and an absolute brainfuck. It has Lewis’s most fully developed female characters, including one of the more intriguingly enigmatic figures to ever appear in the pages of a novel. To John Williams’s claim about Jack’s Return Home being the finest British crime novel, I say Williams got the right author but the wrong title. In discussing Lewis and in focusing on GBH specifically, Derek Raymond wrote, “GBH is a novel as direct as it is stunning,” and “he is an example of how dangerous writing can really be when it is done properly, and Ted Lewis’s writing proves that he never ran away from the page.”

GBH was the last book Lewis had published. In the remaining two years of his life after its appearance he started a couple of literary projects, including a children’s book about a dragon and another crime novel. But none of these ever saw print and in 1982 Lewis’s decades-long alcohol abuse finally saw him to his death. Missing in Action Films of the U.K. has plans to make a new movie based on GBH, but the status of the project seems unclear at this point. If this movie happens, it could be the vehicle that finally brings some widespread notice to one of the great underappreciated writers, who was also an intriguing man.

Brian Greene’s short stories, personal essays, and writings on books, music, and film have appeared in 17 different publications since 2008. He writes regularly for Shindig!, a U.K.-based music magazine with worldwide distribution. Greene lives in the Triangle area of North Carolina with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, and their cat Rita Lee.

Nice piece. Thanks for the introduction to Lewis. Think I’ll go check out his work now.

I have a color wash drawing that Ted drew for me in Barton on Humber. It is signed and dated 1981.

Ada, wow! I’ve seen quite a few of his artworks. He was so gifted. If you have a scan of the drawing and care to show it to me, my e-address is brianjosephgreene@gmail.com

What a great piece.

I’ve long considered Ted Lewis the greatest noir writer ever and would love to know more about his life.

It’s such a great shame that he never achieved the recognition that he so richly deserved whilst he was alive.

Frankly, if Shakespear or Dickens had written hard boiled noir they’d have done it like Ted – His work is just so amazing. If anybody reads this that knew him. Please mail me. I’d love to discuss.

Hi Brian. Long time. Are you still interested as your e mail sends back!! I have been in touch with David Craggs too (and his e mail bounced too!!)

Best

Monty Martijn

Hi Monty. If you look at comment #3 here, that has my current email address. Feel free to drop me a line.

BG