This is a Cold War thriller that has nothing to do with nuclear annihilation or international espionage. The focus is on a murder investigation in East Berlin, and all the players are East Germans.

Readers familiar with Cold War novels set in Communist East Germany will feel at home in the setting and tone that Young creates. Readers new to the genre will quickly feel the bleakness of life in East Germany, from the pollution to inadequate winter clothing to the construction of monolithic Soviet block apartments.

Nothing is quite straight forward. Everyone has something to hide and/or some kind of damage that’s a weak spot that can be manipulated by those in power. Citizens have to walk a straight line to avoid suspicion. These threats are bad, but worst of all is the corrosive force of relentless propaganda and paranoia that wears people down. Everyone is a potential informer spying on everyone else, even family members.

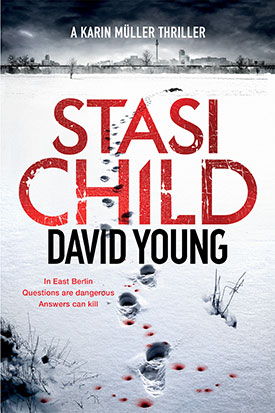

The novel opens in February 1975. Oberleutnant Karin Müller is the highest ranking woman in the People’s Police. She’s proud of the fact that her government is striving to create a more equal and just society. Her rise through the ranks is proof positive that it's working, and now she’s been given a politically sensitive case: to find out the identity of a young woman who was brutally murdered, her body found near the Berlin Wall and made to look like she was fleeing from the West. She’s told, however, not to search for the killer, just find the identity of the victim.

While her professional life is thriving—even if she is in a bit over her head—Müller’s marriage is falling apart and may already be dead. Her husband, Gottfried, is a school teacher who was recently reprimanded and sent to work at a reform school to help him realign with communist values. Gottfried watches Western news programs, which are illegal, and frequents a church where the pastor is under surveillance.

Balanced with the general dread and paranoia of East German life are specifics that’ll make you want to put down the book to look up images on the internet (but after just one more chapter). Wartburgs, Trabis, the KaDeWe. And then there’s the humorous secondary character, the fumbling forensic scientist and Kriminaltechniker Jonas Schmidt. He takes crime scene photos with a Praktica camera and also uses a Foton, a Soviet instant camera that takes photos “just as good as from those American Polaroids.” Young doesn’t throw these items in just to drop names, the photos Schmidt takes help establish early in the investigation that something is very off about the crime scene.

The action swings between Müller’s investigation and nine months earlier in a reform school where a teenage girl is concerned about one of her friends who has started crying every night after lights out. The two storylines kept me guessing as to how they’d merge, and I didn’t see a lot of things coming in this story.

As the story unfolds, Müller’s confidence in her society’s efforts towards gender equality develops hairline fractures. At first, it’s her second in command, Werner Tilsner, fumbling around in his kitchen preparing morning coffee—something, she thinks, he probably only does on International Women's Day. At the other extreme is the shocking number of missing girls in East Berlin, the number of which dwarfs that of missing girls from the whole of West Germany.

At one point, the investigation takes Müller and Tilsner into West Berlin where, for the first time, she sees the luxuries and everyday colors of life in a thriving capitalist culture. Part of her mission requires her to shop, and she enjoys buying soft clothing and warm boots. She luxuriates in a bubble bath at the fancy hotel. Back in the East, she has a moment of guilty pleasure:

In the office, she allowed herself one reminder of the West. She piled the shopping bags on the long table, under the noticeboard, and then lifted out the large shoebox that contained the boots. She opened it, and peeled back the protective tissue paper. Then she removed one boot, and caressed the fur-lined top, as though stroking a cat. A small touch of luxury. Then she looked up at the photographs pinned to the noticeboard. The dead, nameless girl without teeth. The girl without eyes.

Müller dropped the fur-lined boot as though it was infected.

There’s more to the scene than meets the eye, and to say too much about it would lead to spoilers. But it does beg the question about why people embrace the political systems that they do. There’s something about the East German regime’s propaganda that gave Müller comfort, just as there was something about Western values that attracted her husband. And then you have a guy like Tilsner, who seems to be a poster boy for the People’s Police yet can afford a fancy watch that is way above his pay grade. So many questions!

Some are answered, and some are not, but one thing is certain: Young shows how the claustrophobic paranoia of life in East Germany leads not only to cynicism but sometimes to an exhaustion so deep that people give in, give up, and do what they’re told.

As the saying goes, absolute power corrupts absolutely. In Communist East Germany, that power does more than just create lives of splendor for a few, it causes irreparable physical and psychological damage to those without power, thus strengthening a system that feeds on fear and paranoia.

Read an excerpt from Stasi Child!

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Chris Wolak is an avid reader of crime fiction, history, and classics. She writes about books at WildmooBooks.com and is the cohost of the podcast Book Cougars. You can also find her on Twitter @chriswolak.

She denied the royal insult charge, saying she had just worn a traditional dress.