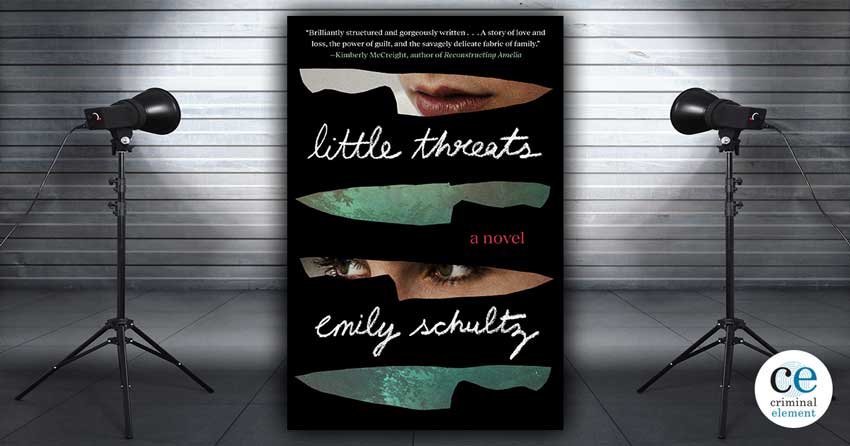

Book Review: Little Threats by Emily Schultz

By Doreen Sheridan

November 6, 2020

Little Threats by Emily Schultz is both a taut whodunit and a haunting snapshot of the effects of a violent crime, telling the story of a woman who served 15 years in prison for murder—and now it’s time to find out if she’s guilty.

Oh, wow. Hello again to being a teenager in the 1990s—especially in the early years when grunge music ruled supreme and provided a voice for many an angsty soul, my own included. Kennedy Wynn is 16 in 1993, your typical, privileged, rebellious white teenager living in a tony suburb of Richmond, Virginia. She and her twin sister, Carter, are best friends with Haley Mae Kimberson, their slightly older, definitely poorer classmate whom a literarily inclined Kennedy dubs the Helen to her Jane Eyre.

Both Kennedy and Haley are involved with 21-year-old Berk Butler, golden-boy scion of another wealthy local family who provides them with drugs, alcohol, and that ineffable sense of embracing a wider world that would deign to even condescend them with a look, much less appreciation and acceptance. Carter, being the more sensible twin, hates Berk’s guts. So she’s not around the night that Berk takes Kennedy and Haley on a drug-fueled ride in his Jeep that ends up with Haley dead and the other two swearing they have no idea what happened.

Kennedy is alone and still high as a kite when she stumbles across Haley’s corpse in the woods the next morning. Realizing that she can’t bring her friend back, she decides to try to make Haley look as peaceful and pretty as possible, an act that will come to haunt her when state prosecutors insist that she killed Haley in the course of an evil, premeditated ritual fueled by LSD and Charlotte Brontë.

At first, no one in the Wynn family thinks the prosecutors could possibly be serious, especially not patriarch Gerry, a lawyer himself. But as the pressure of public opinion mounts, Kennedy is forced to take an Alford plea in order to avoid a life sentence, maintaining her innocence while acknowledging that the evidence is overwhelmingly against her. And so, she goes to prison for 15 years, coming of age in a bizarre sort of limbo stripped of the rituals of normal society.

In prison, she grieves for Haley even as she tries to puzzle together what happened that fateful night. A creative writing class helps a little, as Kennedy explores in writing what she knows and what she feels.

The dead girl never gets to write her own story. She never gets to shake her cramped hand after falling into the words for too long, like I get to do. The dead girl never gets to take a creative writing class taught by an instructor from the local college who is nervous and excited about being in a prison for the first time. The dead girl doesn’t get to put up her bloody, leaf-encrusted hand when the teacher asks, “Does anyone know what epiphany means?” Her side of the story is always unwritten, and that becomes the secondary tragedy. She’s the only one who knows what went down. Everyone else is a tourist in her resting place, even me.

Kennedy’s subsequent reentry to society does not go as smoothly as Gerry, at least, would hope. Carter has been surprisingly distant the last few months before Kennedy’s release date and no longer seems to believe in her sister’s innocence. But that’s only one of the weird, dispiriting obstacles Kennedy will have to contend with as she enters the baroquely constrained half-world of the parolee’s life. She must find a job but is severely limited in what employment is available to her as a former felon. She must live with someone who owns their own home, a weirdly arbitrary requirement given the realities of the modern housing market. Being rich shields her from the worst consequences of failure, but through her plight, Emily Schultz brings to life the harrowing existence of the newly-released prisoner in 21st-century America.

Ms. Schultz’s narrative also features a delicately handled supernatural element, as Haley’s ghost—or something like it—appears to various characters in the story. What’s left of the Kimberson family can’t tell whether they welcome the apparition or disbelieve in it, as Haley’s younger brother puts forward a theory to his still-angry mother.

“Suppose it wasn’t a ghost,” he said. “I remember watching that show Destination Paranormal. They had an expert on saying ghosts maybe aren’t souls. That if someone dies in a traumatic way it’s like it’s been recorded. Like sound hitting a tape. That’s why when you see a ghost they only do one thing and repeat it. Maybe it was that. That tape-record thing.”

“And it was violence that caused that? Funny.” She lit a cigarette and pushed the newspaper around on the table.

“What?”

“That violence would be powerful enough to do that for eternity, but happiness doesn’t cut it.”

That the repercussions of violence overshadow all the joy of Haley’s life is only one of the tragedies of this thoughtful novel that examines not only that particular milieu of the ’90s but also the aftermath, 15 years on, of a single night of violence. The Wynn and Kimberson families struggle in their own ways to come to terms with the murder, and Berk, too, has had to deal with his own role in everything that happened. Ms. Schultz brings her level gaze and compassionate prose to all these fallible people as they finally unravel the truth, evoking the eras she writes of with intimate knowledge and a cultural depth that will resound with anyone else who lived through them too.