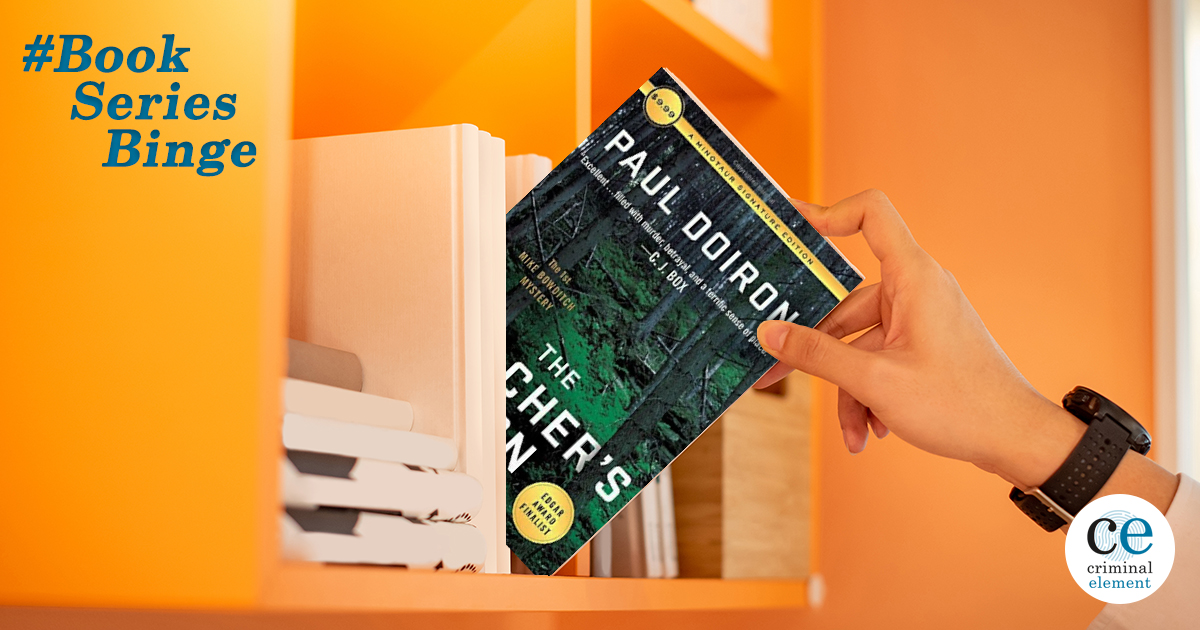

Book Series Binge: Q&A with Paul Doiron and Introduction to the Mike Bowditch Series

By Crime HQ

March 27, 2020Read on for Paul's introduction to the Mike Bowditch series, found in the paperback edition of Book 1—The Poacher's Son.

Describe the first time you pictured Mike Bowditch in your head?

Paul Doiron: This might sound unbelievable, but I don’t have a clear idea what Mike Bowditch looks like. I can tell you he has blue eyes, dark hair, is 6’2”, with a physique that’s closer to a cornerback than a linebacker, that he has a scar along his hairline from a beer bottle broken across his head (plus many more scars on his body not normally seen). I know that many women—and certain men—consider him handsome. But I don’t see his face in my mind’s eye, and I think that’s a good thing. One, because I write from his point of view, and although he doesn’t look like me, I think all human beings have an imperfect idea of how we appear to others. And two, because I want readers to imagine their own versions of the character.

Would you like to live in the setting you created for the Mike Bowditch series?

PD: I already live here! My house is on the Maine Midcoast with frontage on a river that holds brook and rainbow trout. I have watched minks and fishers on my property. It’s not uncommon for me to see a bald eagle flying upstream, usually pursued by a mob of crows. The difference is that Mike resides on a wilder—but real—river, about twenty miles from me. And I don’t have an acre and a half pen on my land containing a half-tame wolf.

Read More: See our other #BookSeriesBinge features here

How has Mike Bowditch changed since you began the series?

PD: That question is better answered by my readers, but I can say that the personal and professional evolution of Mike Bowditch is the defining aspect of the series: charting his growth over time. It might be heresy to say this, but the overarching saga matters as much to me as any one book. I want his evolution to be realistic and compelling. In The Poacher’s Son Mike is such a tortured soul: self-destructive, independent to the point of being arrogant, and yet emotionally mature characters like Charley Stevens and Kathy Frost fight so hard for him, because they see his promise. Mike, in their eyes, is salvageable. I like to think that by book eleven, One Last Lie, he has proven that they were right about his essential goodness and heroism. But he still has more maturing to do. As do we all! It’s not like we ever stop developing as people.

Has your Mike Bowditch changed in unexpected ways since Book 1?

PD: Absolutely. When I wrote The Poacher’s Son, I had no clue I was beginning a series. For most of its composition, I believed I was writing a standalone. I didn’t think about creating a protagonist who would have to engage readers’ sympathies and hold their interest over multiple books. But I realized quickly that I had some raw materials to work with in Mike Bowditch that could set him apart from other protagonists, starting with his youth. It’s been exciting to write about how mistakes can be the crucibles of our character. And I still don’t have a firm plan for how I want his “life” to take shape. As I often say to audiences, if I’m surprised as the author, you’ll be more likely to be surprised as the reader.

How would Mike Bowditch describe himself?

PD: Mike would probably say of himself that he wants to be a better man. He’s become more self-aware as he’s gotten older, and he recognizes that he can still be reckless and insubordinate. In some ways, he has less patience for the failings of people in power because he sees how the system rewards self-dealers at the expense of the earnest and the innocent. At the same time, he has grown more humble as he’s gotten older. He knows what he doesn’t know. He understands now that he can’t save people from themselves. He recognizes his judgmental streak as a flaw in his character. Emotional intimacy is a problem. And yet he wakes up every morning and asks himself, what is the right thing to do? Then, unlike most of us, his creator included, he has the courage to charge off and do what is required, no matter the cost to himself.

Order The Poacher’s Son Now!

Paul Doiron’s Introduction to the Mike Bowditch Series

When I started writing the first words of what would become The Poacher’s Son, I had no idea I was beginning a novel, let alone the first in a long series of novels.

At the time I was working as a magazine journalist, always on the lookout for good stories, and one had recently caught my eye. A bear was rampaging around the farms of a nearby town killing pigs and only pigs. The local game warden pursued the elusive bear the way a marshal might pursue a wily fugitive. The strange saga ended—as in a film noir—with an inevitable death. The bear’s, in this case.

Game wardens had long been of interest to me. In Maine, conservation officers have full arrest powers, equal to that of state troopers, in addition to their responsibilities enforcing hunting and fishing laws. It had occurred to me that someone could write a crackerjack mystery with a warden in the role of detective. But I hadn’t thought the person would be me.

From childhood I had wanted to be a novelist. But for years I had held off attempting anything ambitious because I was convinced I had nothing to say. That was why, when I started a fictional sketch about a young game warden arriving at a farm where a bear had just killed a pig, I was reluctant to admit, even to myself, that I might be taking the first steps in a long journey.

Instead, I allowed myself to have fun. My method was this: I would pose myself a question, then let my subconscious quickly provide an answer. My young warden (not yet named Mike Bowditch) finished his investigation at the farm and returned home. What did he find there? Nothing but empty rooms. Why were they empty? Because his girlfriend had recently moved out. Why did she leave him? Because she was frustrated by his singleminded commitment to his morbid job. What else did he find? A cryptic voicemail on the machine. Whom was the voicemail from? His father.

Who was his father?

It was with that question that The Poacher’s Son announced itself to me as something more than the vignette I was pretending it to be. I was writing a novel. And not just any kind of novel but a mystery with an existential question at its heart: How well can we ever know another human being?

I had excused myself from previously attempting a book because I didn’t think I knew anything. In writing the first draft of The Poacher’s Son, I discovered that I knew quite a few things.

I knew Maine—its landscapes, history, and people—from having grown up here and from having traveled to its most remote corners as a journalist.

As a lifelong sportsman, I knew about the outdoors, having spent uncounted hours paddling in canoes, wading in salt marshes, and bushwhacking through pathless forests. I knew that I rarely saw the natural world depicted in fiction with care, correctness, and curiosity.

And I knew about other things as well. I knew about distant fathers who held their sons to impossible standards of manhood (although my own loving father wasn’t one of them, thankfully). I knew that I rarely saw young men rendered as complex, contradictory beings in novels: with maturity and immaturity coexisting together like two persons sharing one body. I knew too much about self-sabotage and about denial in all its insidious guises. And I knew about betrayal, having been on both sides of it.

I was also beginning to know mysteries again. As a teen, I had devoured the works of Conan Doyle and Christie, but I had lost touch with the genre during my snobbish college days. By the time I began writing The Poacher’s Son, my girlfriend (now wife) had introduced me to contemporary crime fiction, books that were very much works of literature. I was reading Tony Hillerman, P. D. James, James Lee Burke, John le Carré, Walter Mosley, and many others with feverish intensity.

Writing fiction is an act of empathy. It is an attempt to escape the prison of the self and view the world through the eyes of another.

In time I would learn police procedures and forensics. I would learn that the justice system is an absurd but necessary construct. Most of all, I would learn about the lives of Maine game wardens.

One of the great and unanticipated pleasures of writing this series has been the time I have spent in the company of conservation officers.

While I don’t write for their approval, I am always gratified when they tell me I have captured something of their experience that they themselves have trouble articulating.

Writing fiction is an act of empathy. It is an attempt to escape the prison of the self and view the world through the eyes of another. In The Poacher’s Son, I have attempted to see Maine through the eyes of a troubled yet heroic young warden named Mike Bowditch. More than that, I have tried to bring him so fully to life that he seems real to my readers, as three-dimensional as a human being. The best characters, after all, are the ones who aren’t content to dwell only on the printed page. I have this fancy that someday, out in the woods or on the waters, I might actually meet Mike Bowditch. If I do, I hope he forgives me for all the trouble I have put him through.

—Paul Doiron