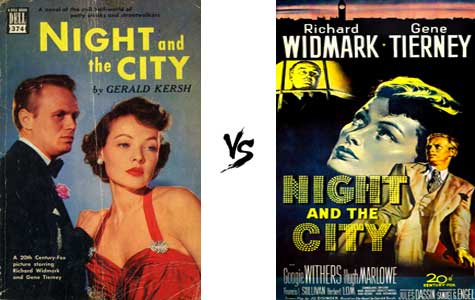

In thinking about Jules Dassin’s 1950 work of film noir Night and the City in relation to the same-named 1938 novel by Gerald Kersh, one striking thing to consider is the fact that Dassin said he never read the book. He apparently fully relied on the screenplay of Jo Eisinger, and his own cinematic vision, to guide him as he took the story and adapted it to the big screen. Was Dassin just too busy to pore over Kersh’s novel, did he not want to get distracted from the tale as it read in the screenplay, or was there some other reason why he chose to not read the book? I don’t know, but the differences between book and film are interesting.

The first thing to establish – and not that many reading this likely need to be told as much – is that both Kersh’s novel and Dassin’s film are superb. Both are influential works of noir that take an unflinching look at a panorama of seedy characters in hardboiled situations. Any lover of edgy crime stories, and/or powerful works of social realism, needs to experience both versions of the tale. Ok, so that’s settled. Now let’s get on with a close look at how the two compare.

Both film and novel are set in London. And both concern a motley crew of hardened characters who are struggling in a joylessly desperate moneyed environment. Primarily occurring in nightclubs and professional wrestling environments, the tale depicts a host of hard-up men and women who are out to make a pound any way they can, within a seemingly hopeless (sewer) rat race. Nearly every person in the story seems to be in a constant state of looking at other people and wondering how many quid they might have on them, and what they might be able to do to get some of that dough. Things like morals and decency to your fellow man and woman get tossed in the gutter like yesterday’s betting sheet, and all in the name of the mighty pound.

One considerable difference between novel and movie concerns the character of Harry Fabian. Brilliantly portrayed by Richard Widmark in Dassin’s film, Fabian is a fellow especially determined to find money-making schemes; he’ll do anything for this purpose, so long as it doesn’t involve steady, legitimate work. He is a guy who makes some of the other unsavory characters from the story look like saints. Nothing is sacred to Fabian as he sets about finding roundabout ways to reel in some loot; he’ll sell people, including those who have been faithful to him, as quickly as he’ll sell any other marketable good. In both versions of the story, Fabian’s greedy interests ultimately take shape via wrestling. Believing this will be his big goldmine, he becomes a promoter of professional grappling. Fabian is pretty well identical as seen through both Kersh’s pen and Dassin’s camera, with two things being different about his character in their respective media: the movie mostly revolves around him while in the book he is just one central player among others; and in the film he is seen to be, at least in some scenes, as verrrrry slightly more sympathy-invoking than Kersh shows him.

In each version of Night and the City, the wrestling goings-on ultimately center around hostilities between two of the fighters: an aged but still-determined classic wrestler, and a younger, less trained but more dangerous man of the ring. Fabian is right in the middle of the conflict between these two, but in the movie he represents the older man and in the book, the younger one. There is eventually a match between the two men, but in the movie (in a painfully but compellingly drawn-out and grisly scene) their bout is unofficial, takes place spontaneously after they’d been having an argument at the gym Fabian runs; while in the book their match is scheduled and officially presented to a paying audience. The result of the match is the same in both versions and is central to the tale, and no, I’m not going to commit a spoiler by revealing that outcome.

The most meaningful difference between the cinematic and literary takes of this saga has to do with the characters besides Fabian. There are certainly plenty of them in Dassin’s film, and they all add color and intrigue. But in Kersh’s book the other people are more prominent. One of the more elemental aspects of the movie Night and the City is its lack of likable characters – nearly everybody in the story is rotten. That’s a big part of what makes it so utterly noir. And while this is true of most of the people in the book, there are more decent humans to be found between its pages than are seen up on the screen, and they figure more into the tale. In particular, Kersh’s book has a struggling couple who are not represented in the film (well, in the case of the woman, not in the same way). The man wishes to be a sculptor and the woman is (initially) a well-meaning soul who becomes his ladyfriend. These two both get reluctantly drawn into nightclub work, and they are decent people who serve to balance out the evil ways of Fabian and other soulless greedmongers in their vicinity. Fascinatingly, that woman (Helen is the character’s name) is the unkind, untrustworthy wife of a sleazy nightclub owner in the movie version, and she is also Fabian’s ex; while in the novel she is a decent, struggling young woman who gets reeled into becoming a nightclub hostess because she is single and has no other way to earn money; and she becomes romantically involved with the hopeful artist, then challenged when his lack of ambition to make money leaves her wondering how they will get by if they decide to make their romantic partnership something permanent. The efforts of that couple to carry out their love life, and for the sculptor to lead an existence that has some personal dignity at its foundation, amid their dire surroundings, are as much a driving force of Kersh’s story as are the exploits of Harry Fabian.

Do these differences make the movie better or worse than the book? No. Dassin’s film takes a long, hard look at the corruption of one ne’er-do-well man’s soul while Kersh’s novel offers a wider view of the lives of several characters who exist in Fabian’s orbit. Both ultimately reveal the shame-making depths the pursuit of money can lower people to, especially when there is simply not enough of it around.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and reviews and articles of/on books, music, and film. His work has appeared in over 20 publications since 2008. His pieces on crime fiction and film have been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Paperback Parade, Mulholland Books, and Stark House Press. He is a regular contributor to The Life Sentence crime fiction web site, and Shindig! music magazine. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina. He can be found on Twitter @brianjoebrain.

See all posts by Brian Greene for Criminal Element.

Been awhile but I think I need to read the book again. Loved it, of course, but preferred the film because of Gene Tierney. A favorite.

Thanks for the comment, David. I’ve gotten behind in my reading but need to catch up on your posts here.