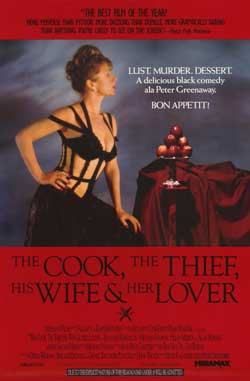

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover is not the first film you're likely to come up with when thinking about British gangster movies. Filmmaker Peter Greenaway, who began his artistic endeavors as a painter, has made a name for himself as a creator of provocative and sometimes experimental works of greater or lesser accessibility (The Draughtsman's Contract, Prospero's Books, The Tulse Lipper Suitcases), and no one would call him a genre filmmaker of any sort. And yet, in The Cook, the Thief, released in 1989, Greenaway wrote and directed a film that has a gangster, Albert Spica, as its central character. The film is not a conventional gangster picture, but it has at its core the ingredients that make up many a basic crime drama: violence, betrayal, romance, revenge. How these ingredients fit together is what makes the film unusual—a film no one but Greenaway, with his distinctive approach to visuals and narrative, could have made.

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover is not the first film you're likely to come up with when thinking about British gangster movies. Filmmaker Peter Greenaway, who began his artistic endeavors as a painter, has made a name for himself as a creator of provocative and sometimes experimental works of greater or lesser accessibility (The Draughtsman's Contract, Prospero's Books, The Tulse Lipper Suitcases), and no one would call him a genre filmmaker of any sort. And yet, in The Cook, the Thief, released in 1989, Greenaway wrote and directed a film that has a gangster, Albert Spica, as its central character. The film is not a conventional gangster picture, but it has at its core the ingredients that make up many a basic crime drama: violence, betrayal, romance, revenge. How these ingredients fit together is what makes the film unusual—a film no one but Greenaway, with his distinctive approach to visuals and narrative, could have made.

But let's start with the plot: somewhere in England, a gangster named Albert Spica (Michael Gambon) has bought Le Hollandais Restaurant, run by the French chef Richard (Richard Bohringer). Every night Spica turns up at the restaurant with his entourage of goons, and this boorish group proceed to offend the restaurant staff and customers. Spica himself is violent and crude, and he holds court from the center of his table. He's a self-proclaimed authority on everything, a person intolerant of dissent. Besides his thugs, he's accompanied each night by his wife Georgina (Helen Mirren), a woman who somehow manages to conduct herself with class and tact while enduring the bellowing onslaughts of her husband. Right under his nose, she takes up with a man who always dines alone while reading a book (Alan Howard), and this affair continues with the help of the restaurant staff. Everyone knows the explosion that will happen if Albert discovers the affair, and sure enough when he does, the cruelty he enacts on his wife and her lover (and a child who helped them) is monumental. His wife's sense of loss is deep. Her lover was everything Albert is not: kind, quiet, thoughtful. Above all, like her, he enjoyed books. He lived for something other than power, money, and eating—the things Albert values. Emboldened by her grief, Georgina talks revenge, and she convinces the restaurant chef to help her. Richard, Georgina, and all the many people Albert has hurt band together. Restaurant staff are among the avengers; so are former members of Albert's crew. The vengeance they take out on him is horrific, as cruel as anything he did to others, but it's exactly what he deserves.

In structure, Greenaway's film hews to the Elizabethan and Jacobean revenge play. This is a type of English drama popular from the late 1500s through the mid 1600s in which the main motivating factor among the characters is revenge. The plots invariably hinge on a real or imagined injury leading to this vengeance, and the plays are blood-soaked. There is violence, insanity, torture, mutilation, lust. The view of human nature is bitter and cynical; the language and imagery are baroque and extreme. Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus is one such example; John Webster's Duchess of Malfi and John Ford's Tis Pity She's a Whore are two others. No act is beyond the pale in these dramas, and to forgive is not a choice that anyone takes. In some plays, the avenger gets revenge and lives; often the avenger dies along with the object of their vengeance (as in Hamlet). Typically also, there is a stoicism or an attempt at stoicism displayed by the primary victim, and in The Cook, the Thief, Helen Mirren embodies this aspect beautifully. Groped by her husband, interrogated constantly, put through all manner of indignities, Georgina manages to keep her poise. She never kowtows to her husband even though she knows it will mean she receives abuse, but you're certain that she's not provoking Albert out of a masochistic impulse. The character she plays here presents a fascinating contrast to her role as the wife (and criminal partner) of Bob Hoskin's Harold Shand in The Long Good Friday, and yet, as with everything Mirren does, a strength comes through. Here of course, you are entirely on her side, and you shudder with nervousness with her when she and her lover, hidden in the restaurant's bathroom for a sexual tryst, almost get caught by Spica.

Not that this is a film where you're invited to empathize all that much with the characters. The sumptuous colors, the painterly compositions, the long tracking shots and the overall formalism keep the audience at a distance and tell you that you're watching a work of artifice. This is most certainly not a gangster film trying, through grittiness, to achieve verisimilitude. The film starts, the opening credits run, and the camera cranes up to two red uniformed figures who throw open a velvet curtain. Our story, like a piece of theater, then begins.

What follows is a scene that typifies a lot of what we'll see later. Albert Spica and his men do something repugnant—force a man to eat his feces, urinate on him—while at the same time Spica talks non-stop, uttering insults, unfunny jokes, coarse observations. The man has a tongue that itself is a weapon, an instrument of humiliation, and he has a continual need to dominate people verbally as well as physically. His verbal cascade reminds one of Ben Kingsley's Don Logan in Sexy Beast or James Fox's Chas in Performance. He also falls in a line of British cinematic gangsters who follow in the footsteps of the Kray twins, Ronnie and Reg, who along with their sometimes savage exploits, carried themselves as though they were celebrities. The Krays would mingle with actors and singers at the clubs they owned, and Albert Spica obviously sees himself aspiring to a world above the level of the violent gutter we see him commanding at the film's beginning. Britain, however, is small. If one wants to grow, one has to look beyond its shores. In The Long Good Friday, Bob Hoskins looked to an American gangster for financial backing and increased legitimacy; in The Cook, the Thief, Spica has his French cook to expand his horizons. The problem is that the French cook is an artist, and Spica has no understanding of art whatsoever. His mispronunciations of the French dishes he eats are pathetic, and he devours his meals without appreciating them. Spica is a monster of consumption, as are his cronies, and they belittle every single thing that's not consumable or that can't be acquired with money. Before he even knows that the book lover is his wife's lover, he exhibits contempt for the man precisely because he reads while eating. “What good are all these books to you?” Spica says. “You can't eat them! How can they make you happy?” And his idea of reading brings the concept of lowbrow to a new level: “I've just been reading, stuff to make your hair curl. You go in that toilet. That's the sort of stuff people read. Not this sort of thing. Don't you feel out of touch? Does this stuff make money? I bet you're the only person to have read this book, but I bet you every man in this restaurant has had a read of that stuff in there. Makes you think, doesn't it?”

When The Cook, the Thief opened, the general view of it was that it presented an attack on the social and economic ideas of the Margaret Thatcher government. Nothing Greenaway ever said refutes this reading, and the film does play as a scathing allegory on the brute force capitalism of the Thatcher years. Equating gangsterism with business and unchecked capitalism is nothing new (We see it in plenty of American films—The Godfather Trilogy and Brian DePalma's Scarface come to mind), but in those stories, the gangster represents the left hand of capitalism, so to speak, the outsider doing through blunter means what the state sanctioned business person does legally. In the self-contained world of The Cook, the Thief, the gangster is in effect the state, and everyone is supposed to dance to his grating, reductive, ugly tune. Even the restaurant patrons have to submit. Though unprovoked, Spica insults one patron, and when the man says he'll complain to the management, Spica declares “I am the management,” and knees him in the groin. His follow-up comment, that what people need is “short, sharp, shock treatment” sounds like it could have come from the Iron Lady's mouth herself. It's quite amusing that when Spica, in one of his rants, demands to know whether Georgina's gynecologist is a man or woman (saying to her it had better be a woman), Georgina's answer touches on a number of points that are sure to drive the socially conservative Spica crazy. Her gynecologist, she says, is a man, Jewish, and from Ethopia. His mother is a Roman Catholic, he's been imprisoned in South Africa, and he's as black as the Ace of Spades. Spica's reaction. What else? A hard punch to Georgina's stomach.

I remember seeing Greenaway's movie when it came out. I found it both disturbing and thrilling. Watching it again all these years later, I find it holds up. Its depiction of crass commercialism trying to dominate everything has, if anything, gained in relevance. It's a film ravishing to look at, with wonderfully scatological language and a memorable score by long time Greenaway collaborator Michael Nyman. The acting by everyone is superb, and in fact it's fun to watch now and think about how many film and TV crime roles the cast members have had during their careers. Besides Mirren, there's Tim Roth as one of Spica's sidekicks, and Michael Gambon went on to play the lead in The Singing Detective, not to mention Maigret. Even Alex Kingston has a part, wordless, as one of the restaurant staff, and she would later appear in the Brit noir pic Croupier (1998) as well as the crime film Essex Boys (2000).

Peter Greenaway never returned to anything resembling a gangster movie again. And there are some who might not consider The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover a gangster film at all. Without question it's a movie that uses gangster film tropes as a means to an end. The violence, torture, and cannibalism on display are all stylized in such a way that they're startling in their own right yet “stand” for something else. What's intriguing is that Greenaway was not the only British filmmaker during this time to turn to the crime film to depict the realities of a political era. As I pointed out in an earlier Criminal Element post, Antonia Bird's Face from 1992 uses a gangster film to analyze Thatcherism and its effect on the country. But that film does so in a more straightforward manner, submerging its critiques in a “realistic” heist plot. Greenaway takes the postmodern approach, using what he needs from a genre to create the effect he wants, merging the components of this 20th Century-born genre with his centuries old revenge play template. The result is a movie both of its time and timeless, and I'd say it serves as a good illustration of the gangster film genre's flexibility. In Greenaway's inventive hands, the genre got a one-off jolt of fierce, cutting energy.

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. A film nut as well as a writer, he co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His Martinique-set crime novel, Spiders and Flies, is available now from Harvard Square editions at Amazon, B&N, and wherever books are sold.

Haven’t seen this since it was in theatres, might be time for a re-watch.

(I knew there was something I didn’t like about Dumbledore…)