We hope you'll enjoy this exclusive look at Kabul, Afghanistan's Green Zone through the eyes of a writer serving there, presented as special, long-form feature in four parts.

1. BEING DEPLOYED – THE JOURNEY BEGINS

Ever wonder what you’d say if someone came up to you and told you it was time to go to a warzone? Most people don’t have a job where that’s an issue, but what if it was? Think about it for a moment. What would you think? What would you say?

More importantly, what would you do?

As I sit here in Afghanistan, I can't help but think about those things that brought me here; the events that occurred to make this a reality. Thinking about it takes me back to the day I was voluntold.

For the record: volunteer + told = voluntold.

It’s a sacred military term we all come to love… and sometimes hate.

“You’re being deployed,” my boss said. Although he grinned, his eyes watched me closely. This was part of the game. How would someone react when they were told they were going off to war? How would I react?

“Sure I am.” I laughed and waited for a reciprocating laugh from my boss, or the deputy, but neither gave in. “Oh, you’re serious.” I looked from one man to the other and felt it for real. Fight or flight. My heart fluttered. My face might have even paled. A tsunami of concern broke in my stomach. This was it. This was that moment. How would I react? How was I reacting? Whatever was happening to my body, my mind was flash-banging through a thousand images of war and fighting, both Hollywood and real.

The dead stared back at me with as fierce a stare as those levied by John Wayne and my grandfather, waiting for my answer. It seemed as if minutes had passed since I’d realized I was actually being deployed. In this all-volunteer military, I was being voluntold to go to war. I could get out of it. I could make up some excuse. Hell, I could tell the truth. The Veteran’s Administration had already established that I was enough of a disabled veteran that I deserved money—as some sort of monetary apology for fucking up my body. My mouth moved and the words came out, “Where are you sending me?”

“Afghanistan,” my boss said.

I realized only a moment had passed. If my face had revealed any of my internal ruminations, I couldn’t tell by looking at him.

“Do you know where in Afghanistan?” I asked.

“Don’t know.” He snatched a yellow sticky from his desk. “Call this number and they’ll fill you in.”

As I took the paper, the phone rang. He answered it and I stood there awkwardly for a moment.

I didn’t know if I was supposed to say something or not. Finally, tired of staring at the back of his head, I turned and left the office. I had a phone call to make. Check that. I had two phone calls to make. I had to call deployments branch and I also had to call my wife. After a moment’s consideration, I took the coward's way out and called deployments branch first.

It's funny. As I look back on that moment, I wasn't scared. This was something I'd wanted to do for so long. Twice before, I was set to go, and my deployment was scuttled. I was beginning to feel like it was never meant to be. Then came the notification. Was I scared? Not the way you think. I wasn't scared for my life. I was scared for all the things I was going to miss. I was scared that something might happen in the life I'd constructed, and I wouldn't be there to see it, to fix it, to be a part of it. This is the hardest thing to get over. It's a hard lesson to learn that life goes on without you. Once you get that, then everything falls into place.

I think I’m really ready to go.

Let's get this party started.

2. DRIVING TO THE GREEN ZONE

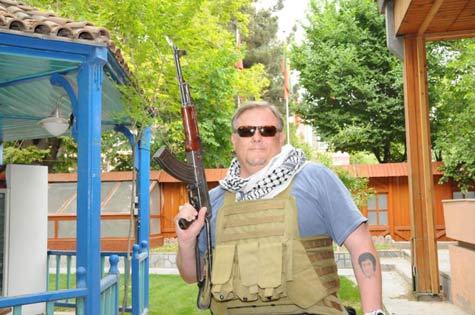

“Put your gear on. We’re heading out,” Scott says. He wears fatigues with body armor and a P229 pistol in a holster on his vest, looking 100% badass in his six-foot-two-inch U.S. Army Command Sergeant Major body.

My driver is a U.S. Air Force Tech Sergeant who wears crazy eyes above a winning boy-next-door sort of smile. As I struggle into my body armor, trying to figure out what the hell to do with all the Velcro and buckles, they shut the substantial back door of the up-armored SUV. I finally climbed in and began fighting with the seat belt.

“Don’t worry about that. It’ll just get caught up on something if we get in the shit,” says Crazy Eyes.

They move their weapon status from amber to green, and we begin moving away from the airport around a dozen hairpin turns bound by concrete barriers to keep the great unwashed and explodable masses away. Just last year, an SUV similar to the one I was in was almost destroyed when a truck pulled up behind it and detonated as they waited to enter through security. The nature of the entrance changed since then, as has surveillance on the lone road leading to the airport.

Coming into the airport was supposed to be safe.

And it probably was.

But we were going out.

I’d been both dreading and looking forward to this moment for two years, ever since I was told I was going to Afghanistan, if not for a lifetime. I hate rollercoasters. I hate fast rides. I hate twists and turns. I hate it when someone else drives. With all of them it’s a lack of control. I understand the psychology of it.

But please explain this psychology—I was about to be driven from Point A to Point B along a route with known terrorists who have proven they can blow vehicles up with improvised explosive devices, vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices, and suicide bombers, and I wasn’t scared. I was freaking excited, and a small part of me in the back of my mind told me that I really should be a little more worried. But I wasn’t. My crazy Tech Sergeant knew how to drive and my Sergeant Major knew how to guide.

So let me set the scene and roll my narrative camera:

You exit the airport sitting in the backseat of an up-armored SUV.

Four-lane streets containing cars parked on either side in places, potholes in front of you, sometimes separated by a thin median, but not always. One-story buildings and hovels line the sidewalks, teeming with people shopping, talking, going about their everyday business. Like the signs to the businesses themselves, they are multi-colored, garish and confetti-colored eye candy to the watchful. Some of them sit. Some of them stand. Others break into a run. Most don’t even notice you, but you can’t help but stand out. You’re in an up-armored white SUV with tinted windows and antennas jutting like an Armageddon porcupine among a country full of Datsuns, Nissans, Toyotas, and the like. So they stare.

Are they curious? Do they wonder who you are? Do they realize you’re the great Evil American, here to eat their children and make the populace the next MTV generation? Are they about to report you to someone down the road for your red, white, and blue soul? Look, one has a phone. Are they calling ahead, activating an IED, or checking if the wife wants milk and eggs?

Crazy-eyed driver keys up a playlist on the radio.

Heavy metal thrums inside the vehicle drowning out every other sound. Every one that is except—

“Drive,” commands Sergeant Major.

We accelerate to fifty and begin to weave through slower traffic down the Great Massoud Road.

Left side, car pulls in front, we swerve and don’t stop.

“Car. Right side. Parked.”

“Got it,” says Crazy Eyes.

We zoom past.

No boom.

Good thing.

Two cars come in from the right at high speed. Looks like they might be trying to block us or just maybe trying to hurry across.

Doesn’t matter.

“Juke right.”

You hold on as the SUV’s tires bite into the Soviet-era concrete on the road. We swerve right, then left, then straight. Whatever the cars are doing, they’re now in our dust.

You notice you’ve been holding your breath.

You breathe.

Mussah.

Serenity Now.

You can’t help but smile.

The brakes lock for a moment and we all jerk forward as a child crosses in front. We’re stopped. Sitting ducks. On the left squats an Afghani man wearing black. His body is turned away from us, but his eyes are watching as he talks into a phone. Damned phones. What’s he saying? Got Milk? Got Eggs? Got Boom?

You jerk back as we accelerate again. You feel like the ass-end of a bullet in CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. We jerk left. We jerk right. Accelerate. Slow. Accelerate again. You’re on the Afghan Fun Ride.

By now, you’re giggling nervously.

“Car right.”

“Group of men on left.”

“Trash pile on left.”

“Motorcycle. See it?”

“Got it.”

You remember the movie Twister and their exclamation of “Cow!” as it flies by in the grasp of a tornado. You half-expect your companions to say that next.

Then we hit the traffic circle. Dear Great God of Roundabouts, what have you done?

It’s a traffic circle in geometry only. Cars and trucks and bikes and horses pulling carts go around it in both directions. They don’t yield. They don’t slow. It’s chaos and we’re going to die.

Only we don’t.

Tech Sergeant Crazy Eyes shoots through three scant openings, slips past a donkey cart, and next thing you know, we’re roaring down another street, barely avoiding being T-boned by a bus. Like the Incredible Hulk through the eye of a needle, we somehow make it through.

“Car. Right.”

“Truck. Left.”

Accelerate to seventy miles per hour.

And finally, “Cow!”

In an effort to keep the haggard beast off our hood, the SUV bites hard with the braking. We slide by, clipping its tail, which snaps nattily back to remove a fly from a lazy, bored eyelid, shielding a gaze that says, What? Me worry?

Then the school children.

We stop.

Like emperor penguins, they waddle across the road in their white-and-black school uniforms. What can we do? We can’t ram them. We can’t go around.

Suddenly, you’re hyper aware of everything around you. You can feel the ticking of the engine like knocks on your heart.

A child laughs.

Another screams.

The sounds of their childhood are like heat rounds shooting towards you.

A car honks behind you.

“I don’t like this,” says Crazy Eyes.

You think to yourself, Fuck. If he’s worried, then you should be, too.

But the sergeant major calms you. “Easy, now.”

As the music changes to Nickleback’s “Animals,” and you get to the line where the devil needs a ride, you see the children are gone, and you’re accelerating and the song might be about anything at all, even sex inside a car, but you don’t care because the beat matches the speed you’re going, and the way the people and trees whip past the SUV makes you feel like you’re moving even faster. While your right hand is on the oh shit handle, your left is tapping to the beat on your left leg. You’re two parts of the same being. The right part of you is scared while the left isn’t.

You notice the increased presence of police in gray uniforms carrying AKs. You feel safe.

“See those guys with the AKs?” the Sergeant Major points.

“Yes,” you say.

“They don’t like us. Watch out for them,” he says.

Watch out for them? Like now? Seriously? Those police right there with the AKs?

Then we pass a building under construction. It’s going to be big, whatever it is.

“They’re building a Hilton there,” the Sergeant Major says, playing tour guide.

“Shit’s going to get blowed the fuck up,” Crazy Eyes says, channeling Nostradamus and Bobcat Gothewait.

Shit’s going to get blowed the fuck up.

Fucking priceless.

“We’re here,” says Crazy Eyes.

Sergeant Major leans across the seat and turns to you. “Welcome to the Green Zone.”

You feel giddy. You feel sad. The ride is over. Part of you is happy and part of you wants to do it again. And part of you wants to fling open the car door and throw yourself to the ground thanking the Great God of Cannonball Runs that your shit didn’t get blowed up.

But then all those parts become one, and you realize you’ve done something no one back home can every appreciate. No essay or book or story or late night yarn will ever be able to convey the sheer joy and fear you felt simultaneously. It’s something where you just have to be there to know. It’s something that you survive, and in the surviving, you become a part of the club that understands such things.

3. TWILIGHT OF THE GREEN ZONE

The Green Zone is not at all what I expect. To tell you the truth, I don’t know what I expect, but what I see isn’t it, whatever that is. It’s not that I expect green streets and green buildings and green people. That's silly. I just expect something… different. Perhaps after six months I’ll be able to express this inexpressible difference, or it might mean I’ll have to travel to another war and visit another Green Zone to compare, but I know this isn’t what I thought it was going to be.

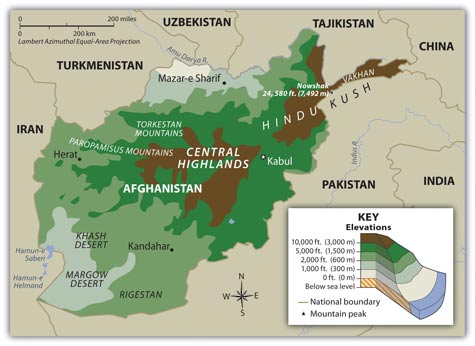

As we enter the Green Zone, the first thing I notice is the concrete. There’s more concrete in the walls and barricades of the Kabul Green Zone than the interstate stretch from Los Angeles to Barstow.

Some indiscernible dust-covered trees line the streets. From the back seat of our up-armored SUV, I notice an immediate change to street traffic. Gone are the throngs of folks going about their business. There are still a few street peddlers and beggars, but the number has been reduced ten-fold. After the cacophony and furious energy of the drive from the airport, the Green Zone itself feels like a dusty street in an Old West town: the only thing missing is a pair of gunslingers, facing off, and someone whistling the theme song to a Clint Eastwood western.

Three soldiers hurry down the street, harried by children as if they are birds trying to get at some hidden food. Although the soldiers are in full body armor and carrying multiple weapons, their attitude towards the children is universal.

They try politely to push them away, but the children will not be deterred. I know the problem right away. I’ve been to enough countries to know that even eye contact can gain their unwanted and furious attention. Let me emphasize, human compassion isn’t a mistake, but at certain times, we can become victimized by it. Like by these children, who have more professional sales acumen than a dozen Amway salesman, and more diligence than a friendly Fuller Brush man.

And like those old documentaries of wildebeests being chased by great cats on the Serengeti Plane, one soldier falls behind the other. I want to roll down the window and shout for him to watch out, but the windows are locked. So I’m forced to watch as two children on his right tug eagerly on his jacket as a third child, a beyond-cute young girl shoves her arm elbow deep into his other pocket, liberating whatever he has in there. She nods, and the children run off, laughing, just like any other children in the world, just like they hadn’t successfully robbed a fully-armed soldier.

We drive on, now moving slightly faster than walking speed. The only other cars around are other up-armored SUVs, one or two local cars, and nothing else.

Then I see the man with no legs. As I try and think up words to describe him, I come up with fervent and angry, but then I think angry is an unfair term. Maybe then fervent and insistent. Yeah, that’s it. I’ve mistaken insistence for anger before, like when my drill sergeant was insistent that I do something, then he was angry about it. Yeah. Insistent. But he seems angry too. I can’t get past that. But let me back up and describe what I see.

Our SUV is stopped in line waiting to pass through one of the many “gates,” each one making an individual safer than the previous “gate.” Outside my window is a man, scurrying about like a spider on a skateboard. His limbs are moving so fast, it’s not until he slows down that I notice he only has two limbs. It takes a few more seconds to figure out if they are arms, legs, or a combination of the two. When he finally halts his motion, at the back bumper of the up-armored SUV in front of us, I see why I am so confused. He wears canvas shoes on his hands, which he uses to both propel himself back and forth, and to slap the sides of the SUVs. His trunk rests on a flat wooden cart beneath a shawl of a blanket, on which he somehow keeps his balance.

But this man is not handicapped. He might not have legs, but he has eyes and the power in those eyes is enough to close the gap between him and those unlucky enough to meet his gaze. I somehow know this right away. I try not to look directly at him, but every time my traitorous eyes look into his, he surges towards me with wind-milling arms and his insistent-angry eyes. It’s as if he’s challenging the entire universe.

His gaze makes me feel insignificant. After all, how can I speak for the universe?

He bangs his canvas shoe on the side of the SUV, and it makes me jump. Scott and Crazy Eyes laugh at me as I meet the no-legged man’s gaze. It’s fueled with an inviolate authority, an incomprehensible demand for something I cannot give. Even if I gave him everything I have, I know it will not be enough. He is Afghanistan and I can’t help him.

Then as the SUV moves on, I feel grateful, and a little guilty.

It really is too much.

We creep forward and make a few turns. Several women have blankets laid out with charms and sundries. Now this, I recognize. Since before Hannibal crossed the Alps, outside every military compound sit women selling their wares—small trinkets of the conquered to be sent home as trophies. However inconsequential and insubstantial the piece may be, the price of the item grows as the narrative increases.

One stands out. I only see her for a moment, hunched over her blanket, carefully arranging the pieces as if it were a game of capitalistic chess. Then she looks up. We see each other. She flashes a peace sign and our gazes meet. Amidst her wrinkled dark skin and even darker hair, glowing from within the shadow of her scarf are bright blue eyes. It stops me for a moment and the world goes into slo-mo. I suddenly know her. She is a child of the Soviets. I think of our own American-Asian kids spread across Vietnam, Korea, Okinawa, Thailand, and the Philippines. I think about how they are treated—outcasts with blue eyes, reminding everyone who sees them about a war just as soon forgotten. Beauty condemned. My own blue eyes—myself a child of war a millennium removed—are accepted. Would it take her as long? Where does beauty start and the guilt of survival end?

Crazy Eyes catches my gaze in the mirror. “Not what you expected, is it?”

“I don’t know what I expected,” I say, not being entirely honest.

“Whatever it was,” he says, with the wisdom of Solomon, “It wasn’t this. That’s for damn sure.”

Soon, we’re pulling through a last gate, and I see military men and women from more than a dozen countries. Scott jumps out and ground-guides us so we don’t run over anyone. I watch the people as they pass. The memories of the race from the airport, the children, the man with no legs, and the woman with blue eyes fade as I begin to take in the details of my new home.

We pull to a stop. Scott opens my door.

“Get your shit together. I need to go find you a room.”

As I step outside and plant my feet on friendly ground, looking at my razor-wire twisted horizon, I take a deep breath.

Six months.

I have six months of this.

“You okay?” Scott asks.

I shake it off. “Yeah. Sure. Just taking it all in.”

“Don’t do it now, or else you’ll have nothing to do for the next six months.”

In the back of my mind, Rod Serling and Bart Simpson compete for a comeback. But instead of saying anything, I grab my stuff and follow them, towards my new home.

4. AN AUTHOR’S WAR DESK

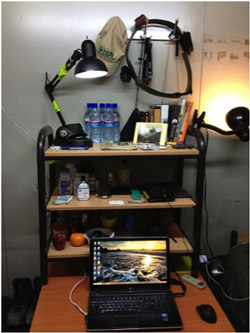

My office at home has lots of space. Desk covered with comic book covers. Arizona sunlight streaming in. Dogs basking in the rays. Books galore. Pictures of friends and past literary conquests.

Afghanistan has none of that.

I live in a fifteen-by-fifteen square-foot space. The room is a thirty-foot long metal box, or can, as we call it. It’s basically one of those cargo containers you see on a ship or a train or part of a truck. But instead of carrying boxes of Wheaties or toilet paper, it holds people. Sometimes two to a room, sometimes three. I’m lucky enough to only have two to a room and I have the back of it, so I get the window.

Some window. When the Afghan sun beats down and begins to bake the box, you want to open the window, but to do so invites mosquitoes in. They swarm. They bite. They have malaria. But you can block them out if you lower the metal-armored blackout shades. It’s funny that a bullet won’t penetrate the cover for the window, but it will penetrate the side of the can. I don’t think they thought that through.

But at least we have air conditioning. That’s the high-pitched whining noise that’s creating the mildew-smelling swirl of lukewarm air. Don’t worry. You get used to it. After all, it’s better than breathing the air outside.

Inside my space, I have a wall locker, a bed, and a desk setup—and I feel lucky to have it. Some folks are stacked three and four to a room like mine. Housing is in a shortage, so to have enough space to call my own is a luxury. I have Afghan rugs on my part of the floor and a curtain to separate me from my neighbor. We can hear each other and smell each other, but somehow, not seeing each other is more private.

What's there? Let's see if I can give you a tour. Gunbelt, with quick release holster for my Sig Sauer P229, spare magazines, and knife made by an artisan in Maine with a Damascus-style blade and wooden-inlaid handle. Hat for when it rains. Headlamp for when the power goes out. Some books (Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain, Connie Willis’s stunning two books Blackout and All Clear, a copy of The Paris Review, Chakras for Dummies, and two others I don’t remember. Lots of water. A book of postcards from the National Gallery of Art—Hudson River School—to remind me of the beauty of America. French soap to wash with once a day. A compass from my wife with a personal inscription about finding my way home. Some fruit from the mess hall. My laptop. Random pills to keep me alive and in decent health. Kindle. Ear buds. Pocket knife. Ray Bans. Silverware I liberated from the mess hall. You can see my boots to the left and my single-wide bed to the right. A little cologne to keep the stench away. Reverse-osmosised water, of which I drink about 8 a day.

I've already edited Age of Blood: A SEAL Team 666 Novel here, worked on a short story and a comic book with William F. Nolan. It's a good space. I have tunes to listen to, and if the sounds of helicopters and vehicles and the BIG VOICE and small arms fire get too loud, there are always my noise reduction headphones.

I look forward to doing more work there.

In fact, I wrote this essay there.

And when I'm done, I'm coming home.

Photos courtesy of the author, except additional Kabul street image via DW.De, Kabul schoolchildren via TKG.af photo project gallery (Najibullah Musafer), Green Zone blast barricade and pedestrian via janipchase.com, and cow via Wodumedia.

Weston Ochse is the author of ten novels, most recently SEAL Team 666, which the New York Post called “required reading” and USA Today placed on their “New and Notable List of 2012.” His first novel, Scarecrow Gods, won the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in First Novel and his short fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. His work has appeared in comic books, and magazines such as Cemetery Dance and Soldier of Fortune. He lives in the Arizona desert within rock throwing distance of Mexico. He is a military veteran with 29 years of military service and is currently stationed in Afghanistan.

I am a big fan of Wes Ochse fiction – but I am truly impressed with this non-fiction piece. Wow – he really brings us up close and personal. Read this essay – it is well worth the time to read it and to pass it along. Once again – impressive!