Guerrilla Growing and You: An Aspiring Criminal’s Guide

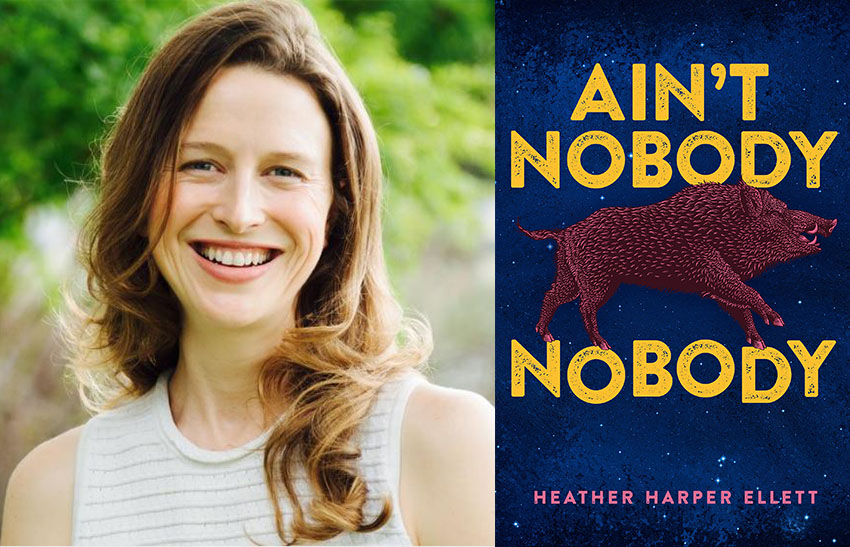

By Heather Harper Ellett

October 3, 2019

In August of 2014, a deer hunter stumbled upon a hundred thousand marijuana plants growing in untended woods in Southeast Texas. The DEA would estimate the plants’ worth at close to $175 million dollars. The setting was enough to make any crime writer drool: a beautiful woods with acres of lacy green plants, an abandoned campground with rifles, ammunition, water bottles, and tents. And a complex irrigation system stealing water from the river. The find seemed like a fluke in these sleepy backwoods. But just weeks later, the feds found another marijuana field of similar size, also worth millions of dollars.

If you’re a crime writer, this kind of “coincidence” makes you think. If you’re an aspiring criminal looking for a career change, it really makes you think. $175 million dollars for six months of tending to a plant whose most dangerous side effect is a massive jonesing for ice cream and Cheetos. Plus you get to hang out in gorgeous woods all day. In many ways, guerrilla growing sounds like an easy and profitable crime, as well as an act of defiance against far-too stringent drug laws that disproportionately target poor and minority cultures. But let’s say you wanted to take up this vocation: how exactly would you pull it off?

While researching my novel, Ain’t Nobody Nobody, a murder mystery inspired by this real-life 2014 bust, I gained an informal education in guerilla marijuana farming. Choosing an ideal locale presents a Goldilocks scenario for the would-be guerilla grower: not too shady, not too open. The plot of land must be obscured enough as not to attract unwanted attention from cops and busybodies, while simultaneously allowing enough sun for the light-greedy cannabis plant. The ideal location for your farm is a stand between 4-10 years of age, with no ATV or hiking trails in the vicinity. The trees can’t be super tall as to provide light but they must provide enough cover that it would only be visible to helicopter or satellite. Guerrilla growers have been known to go into young stands, chop the trees down, and fully farm a couple of acres. Older timber is not as desirable. The overgrowth is too shady and it’s much, much harder to clear out old trees with deep roots without drawing unwanted attention.

Unsurprisingly, information abounds for the would-be grower. You could easily burn an afternoon on a subreddit debating the merits of lime versus sulfur to neutralize the acidic soils found in a pine woods like those in my native East Texas. Another popular topic is how to keep pests away, like deer, rabbits, and raccoons. Blood meal and barbed wire are two favorites—even the words make a writer swoon—but most aspiring growers agree that simply dropping trou and peeing around the plants is the best deterrent. But as one user complained, “I gotta lot of plants, and I can’t pee that much.” Hence, blood meal.

City people may not understand how so much land can go untended long enough for someone to grow acres of plants unnoticed. Think about it like this: you undoubtedly have drawers in your home that are used infrequently, forgotten about. How often do you open that drawer where you store Christmas wrapping paper? Now, what if someone knew you weren’t going to open that drawer anytime soon? Maybe store a few of their own things in there? Creepy, huh?

The aspiring grower may be interested to know that many foresters and landowners are stumped as to how cartels and non-locals find out about their land. If you’re interested in pursuing this new career, you may simply find some land and observe it for a year or so. Or if you’re from out of town, you might handsomely reward a shady local for tips or hire a carefully-placed informant among the throngs of timber company contract workers who plant new tree stands. After all, you’re about to make bank!

If they pay for the right to hunt on property, they will patrol that property. Landowners have even been known to offer cheap leases in exchange for the hunter’s pledge to patrol the grounds.

The problem of guerilla marijuana growing has been a real one for Daniel J. Hale, Edgar-award winning crime novelist. His family has owned thousands of acres in rural Arkansas for almost two hundred years. The marijuana threat came to his family’s attention almost fifty years ago, long before the East Texas busts of 2014. His father attended a timber conference where he learned about a family’s land being confiscated because someone had planted cannabis on it without their knowledge. Because this unfortunate family already had a questionable relationship with the local sheriff, they were charged with the crime. Hale’s father was concerned something similar could happen to their land.

Since then, the Hale family has been diligent in fighting would-be growers. They lease their land to hunters, as a way of keeping the land occupied, the rural equivalent of leaving your television on when you’re away to dissuade burglars. Hunters are territorial. If they pay for the right to hunt on property, they will patrol that property. Landowners have even been known to offer cheap leases in exchange for the hunter’s pledge to patrol the grounds.

Hale’s family also utilizes a program called Drone Deploy that stitches Drone images together for a trained eye to analyze. More sophisticated programs look for specific color gradations that point to illegal activity. “It can do 200 acres in about thirty minutes. It takes two hours to do something that used to take weeks,” Hale says.

Regular airplane and drone surveillance by the DEA and private landowners have slowed activity for aspiring growers, but criminal technology is improving too. In a fascinating article in The Atlantic, Midwestern cornfields have become a new target. Cornfields provide a better combination of nutrients for marijuana, plus air surveillance only picks up on large pot plots due to color difference. Savvy growers have taken to using a GPS to map out smaller patches that would go undetected.

While many of the larger busts in Texas and California have been tied to Mexican cartels, local growers can pose a big threat despite smaller operations. In fact, Hale says that most of the operations he’s heard about are local. “We’re not talking about some hippies with a few plants. Even if they’re growing a smaller plot, that’s still tens of thousands of dollars. These guys will kill you as soon as look at you.”

The foresters I interviewed received no training in their Master’s programs, though how to mitigate possible danger is a hot debate topic. If you’re walking in the woods alone, is it better to look like an ignorant, innocent hiker and hope that a potentially dangerous person lets you be? Or is it better to be armed and possibly be able to fight back should you run across something sinister? But then, at a distance, you could be confused for law enforcement and present yourself as a bigger threat. Admittedly, most of them do not see it as a grave threat. “I’ve walked the woods every day for decades,” one forester told me, “and I’ve never seen a plant in my life.”

See More: Review of Heather Harper Ellett’s Ain’t Nobody Nobody

In many ways, the aspiring criminal could think marijuana growing to be a victimless crime—no worse than a good graffitied wall. But one of the great ironies of a crime that purportedly embraces a Mother Earth-loving counterculture is the devastating environmental impact. The aspiring guerilla grower should think beyond the miles of plastic irrigation lines to bring water to the plants (The average marijuana plant needs 900 gallons of water for a single growing season). They should think beyond the deforestation and fertilizers that throw off the delicate balance of a forest’s vegetation. Think instead about Sequoia National Forest in 2018, where animals were being poisoned in droves by an unidentified substance. The culprit was incredibly toxic rodenticides (illegal in the U.S.) sprayed on an illegal grow site. Those tainted plants were found and destroyed. But many tainted plants are not discovered. And those plants are smoked. By humans. Who are probably innocently listening to Ben Harper.

And despite the money and our ridiculous marijuana laws, all of this just might make any would-be grower think twice before making a career change. And make any good crime writer get right to work.

About Ain’t Nobody Nobody by Heather Harper Ellett:

Still reeling from the scandal that cost him his badge, Randy Mayhill—fallen lawman, dog rescuer, Dr Pepper enthusiast—sees a return from community exile in the form of a dead hog trapper perched on a fence. The fence belongs to the late Van Woods, Mayhill’s best friend and the reason for his spectacular fall.

Determined to protect Van’s land and family from another scandal, Mayhill ignores the sherriff who replaced him and investigates the death of the unidentified man. His quest crosses with two others: Birdie, Van’s surly, mourning daughter, who has no intention of sitting idly by and leaving her father’s legacy in Mayhill’s hands; and Bradley, Birdie’s slow, malnourished but loyal friend, whose desperation to escape a life of poverty has him working with local criminals, and possibly a murderer.

A riveting debut novel about family and loyalty, old grudges and new lives, AIN’T NOBODY NOBODY is like a cross between Faulkner and “Breaking Bad”, from a talented new writer with an authentic Texas voice.

Comments are closed.

Ms. Ellett makes some excellent points. Her debut novel sounds like a winner.

These guys offer help with academic assignments, whether it’s a high school essay or a PhD dissertation.

You can easily check out the best academic help provider in the UK by clicking above.

I am really happy to say it’s an interesting post to read . I learn new information from your article , you are doing a great job . Keep it up