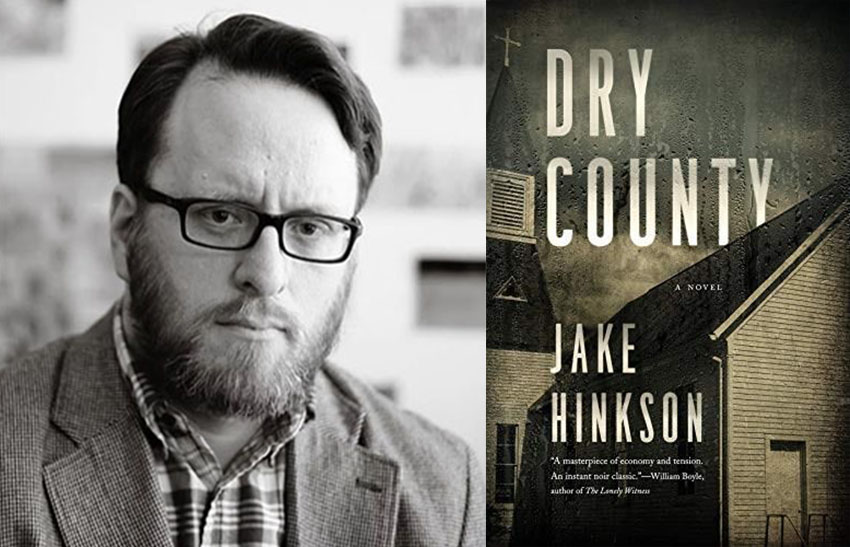

Interview with Jake Hinkson, author of Dry County

By Scott Adlerberg

October 14, 2019

It’s been four years since a Jake Hinkson novel appeared in the United States, but now the wait for a new book is finally over. His newest, Dry County, explores terrain familiar to Hinkson readers, rural Arkansas, while at the same time going places Hinkson hasn’t gone before. The story takes place in 2016, just before the presidential election, and centers around a small-town preacher named Richard Weatherford. He’s a well-respected man in his community, a voice of authority, but he also happens to be a man with secrets. When a former lover blackmails him, putting everything he holds precious at risk, Weatherford finds himself at wit’s end and embarks on a series of actions that have consequences for the entire town. Dry County brims with tension from its opening page and proceeds with a briskness and an economy that Jake Hinkson has mastered. I spoke with him about his particular noir world and how he approaches creating characters who may not seek out trouble but find themselves being pulled into very deep and dangerous water.

***

Scott Adlerberg: In Dry County, you set the story in Arkansas, a place you’ve brought readers to before, but this time you work on a bigger canvas than you have in previous novels. You tell the story through the shifting perspectives of several narrators, creating a kind of mosaic of a small town. What prompted you to tell the story this way?

Jake Hinkson: My previous books have all had a single narrator because I like locking into one perspective and following it all the way. It’s psychologically confining, which is challenging and fun. But Dry County demanded more perspectives because there was more than one person driving the story. What happens with one person’s individual story has repercussions in the other stories. So the form of the narrative evolved along with the narrative itself. For instance, the last addition I made to the roster of narrators was Penny, the preacher’s wife. And she turned out to be, in a way, the key to the whole book. Plus it was just a hell of a lot of fun writing in these different voices. One person is cold and thinky, while another is kind of a well-meaning emotional goofball. And so on. Playing those different voices and perspectives off of one another was my favorite part of writing the book.

***

Scott: They serve as great counterpoints to each other, no question. Now the book is set at a critical moment in recent US history, 2016, not too long before the presidential election. This seemed like the most overt reference you’ve made in your books to politics, and yet at the same time, I love the subtle way you handled it. The stakes of the election, the coming of Trump, is kept in the background as the plot unfolds. There was no hammering the reader with political dogma, as I’ve come across in some books since Trump’s election. How did you work out just how to calibrate and thread into the story the political stuff?

Jake: Oh, I just think that a little bit of politics goes a long way. This book is deliberately set during the rise of Trump, and the darkness of the story reflects my feelings about the state of American politics and society. At the same time, though, I think that when novels get preachy they break their spell. When an author stops the story to say, “And here’s what I think about some no-good politician” I’m taken out of the story as a reader. It brings the narrative to a dead halt. No matter how impassioned the soapbox sermon might be, or even how much I might agree with it politically, as a storytelling device, it seems cheap and cheesy. It’s like I’m reading somebody’s Facebook rant. Besides, Donald Trump doesn’t deserve to be in my novel. He doesn’t deserve to take up any more space in my psyche or the psyche of my reader.

There are no monsters, just human beings with monstrous ideas.

Scott: The book certainly continues the theme of tortured Christianity in your books, hypocrisy, people in conflict with themselves in terms what they may believe in and aspire to and what they actually do. Where do you place the preacher, Weatherford, and Penny as well, his wife, the first lady of the local church, along the spectrum of your rogue’s gallery of believers and pretend believers in your fiction?

Jake: Richard and Penny Weatherford start out the book as a comfortably married couple. (Notice I didn’t say “happily.”) Over the course of the book, they’re forced into a confrontation with themselves and with each other. This conflict is driven by the disparity between who Richard is and who he wants to be (and how he wants to be perceived by others). As you pointed out, I’ve written a lot of religiously conflicted or even downright tortured characters, but I think Richard and Penny are for all their dark deeds, the most human of my “bad preachers.” I had so much fun writing them.

See More: Criminal Clergy with Jake Hinkson

Scott: I couldn’t agree more. They’re very human, and their marriage and family life are very convincingly portrayed. You got the rhythms and tensions, and comforts, as you point out, of married life just right. And the things they do remind me of a Ruth Rendell quote I always liked. Of criminal motivation, she said: “Crimes are more often committed out of fear than wickedness. People lead frightened, desperate lives.” Dry County kind of lays out this idea to a tee, but I was wondering what you think of this idea in terms of crime and how you approach the motivations of your characters.

Jake: I’ve never heard that Rendell quote, but I love it because I don’t believe in monsters, of either of the supernatural or human variety. We like the idea of a monster because, in strange way, it makes us feel safer. Because a monster is an other. It’s out there. “How could someone commit that evil deed?” we ask. “They must be a monster.” No, every evil thing that’s ever been done on this planet was done by a human being. There are no monsters, just human beings with monstrous ideas. People do what they do out of a stunted pathology or adherence to some twisted ideology. That’s ultimately scarier, and truer than the idea that there’s a separation between us and them, between human beings and the monsters who lurk in the dark.

***

Scott: You’re a big film fan of course—your book on film noir, The Blind Alley, is one I recommend to anyone who loves film noir—and sometimes, though not overbearingly so, one can see film influences in your novels and short fiction. From the film noir influence in a number of tales to Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring in your short story, “The Serpent Box”. In all honesty, whose writing is not influenced by film nowadays? At least among crime and thriller writers. Dry County, as we talked about earlier, is a bit different than your earlier books, working on a larger canvas than the others, drawing the portrait of a town, and often focusing on domestic life. Is it possible that, just a bit, Dry County is Jake Hinkson’s version of a domestic thriller? I sort of felt that while reading. Did any specific films or types of films in any way play a part in influencing this book?

Jake: I think that’s an astute point. Dry County definitely owes a debt to the classic domestic noir, especially something like Holding’s The Blank Wall, which is still the best classic noir that most people haven’t read, and the movie version, The Reckless Moment, that Joan Bennett made in 1949. Both the movie and the film (as well as the Tilda Swinton remake The Deep End) situate their drama around quietly twisted family dynamics. That’s also true, ultimately, of Dry County.

***

Scott: Each of your books is very tight and well-plotted. They unfold with the kind of nightmare logic, the unrelenting build-up of tension, that you get in classic noir films and the great noir writers of the forties and fifties. There’s absolutely no padding. I was wondering: when starting a new book, what tends to come first for you? Is it the plot or a plot idea? Or do you start from a character? Or perhaps something else?

Jake: Novels start in different ways for me. A scene, a character, sometimes just a line of dialogue or an opening line. Dry County began with a line about Black Saturday. “Christ died on Good Friday and rose again on Easter Sunday, but on that dark Saturday, his followers trembled alone in their fear and doubt.” The line morphed and changed as the story grew, but that was the seed, the idea of setting a story about religious doubt on the Saturday between the crucifixion and revelation. I usually begin book projects that way, just messing around with little ideas until one starts to grow and turns into something.

***

Scott: Have you started a new project, or finished one already? What’s on tap next?

Jake: I’m working on the next novel. About two-thirds of the way done, and I’m really enjoying it. That’s a good sign, when I can’t wait to get back to my characters.

About Dry County by Jake Hinkson:

A dark vision of American religion and politics, Dry County is a portrait of a man willing to do anything to hold on to his power―including murder.

Richard Weatherford is a successful small-town preacher in the Arkansas Ozarks. He’s a proud husband and father of five, and has worked hard to grow his loyal flock with strong sermons and smart community outreach. But while Weatherford is a man of influence and power―including a big force in local politics―he’s also a man with secrets.

In the lead up to the 2016 presidential election, Weatherford’s world is threatened when he’s blackmailed by a former lover. Collecting the money the blackmailer demands will be a nearly impossible feat, especially over Easter weekend, when all eyes are on him. So Weatherford will have to turn to the darkest corners of their small town in a desperate attempt to keep his world from falling apart.

Exploring a divided country and a cracked façade through the alternating perspectives of Weatherford, his wife, his lover, and other town residents, Dry County is a powerful story about how far some will go to keep hold of all they know―and all that others think them to be.

Comments are closed.

Such a great title. Looking forward to this one.