In December of 2012, in order to do research for my novel The River at Night, I embarked on a nine-day trip to the hinterlands of Northern Maine, the storied Allagash Wilderness which sprawls out over 5,000 square miles of rivers, lakes, and forest. The plan was to interview people who had decided to leave traditional society behind.

I didn’t know a soul up there, so I called the chambers of commerce in towns from Orono to New Sweden to Fort Kent, as far north and west as you can go until the road ends and the forest begins, which is just past a little town called Dickey.

Everyone I spoke to on the phone said: “Well, these folks don’t want to be contacted. That’s why they live off the grid … but I do know someone who knows someone….” Soon, I was able to line up half a dozen interviews with people who had decided to disappear. Armed with a reluctant blessing from my husband and a backpack filled with power bars, warm clothes, and mace, I took off on the twelve-hour drive from my home in Massachusetts.

Billy

There wasn’t a lot of eye contact when I shook Billy’s hand on the shoulder of the road at the 101st mile marker on Route 1, just north of Caribou, Maine. Along with his horse Freedom, Billy and I stood next to my car on the desolate highway as he arranged the saddle so I could climb on behind him. A full-bearded, gruff-looking man in his mid-50s, Billy had agreed to an interview only if he could take me to his place on horseback—an hour’s journey through the Maine woods in winter. After we shook hands, he asked me if I was still up for this; I said I was.

I got on the horse behind him, wondering about my sanity. Billy had been described to me as a family patriarch who said goodbye to society thirty years previous, decades before off-the-grid was a “thing.” As we rode, my arms around this stranger’s waist, he didn’t talk much except to say that his wife didn’t like him a whole lot these days, having borne him five children, each a home birth, something he had insisted upon and she dreaded. “Our boy’s nearly three years old, and she’s still pissed about it,” he said. He turned around and grinned at me, adding, “but hey, maybe she still likes me. She hasn’t left me yet.”

We rode through the woods on a path only he knew, coming up on a ridge that looked down on an empty looking valley. I felt like I had entered another century when I walked onto his land. His log home was painted black, and I saw no one around—just some sheep and sad looking dogs. I fingered the small aerosol can of mace in my pocket, wondering if its time had come … but soon his wife came out to meet me: grey hair, grey-faced, grey man’s coat, smiling like she rarely did it.

Billy showed me his vast collection of guns and knives, the smoking house where the meat hung, and the root cellar. His wife and two older daughters, one with a sixth finger, fixed me a lunch of eggs and bear meat with some kind of wild potatoes. The younger kids played with plastic knives and guns. Billy told me he had enough food stocked to survive the end of the world and that he had dug half a dozen bunkers in secret locations.

Before we left, he made me sign a piece of paper—the old fashioned carbon copy kind—that said I would not disclose any information about him, his family, or the location of his homestead. After I did so, he looked me in the eye long and hard, tore off and handed me my copy of the agreement, and swung back up on his horse.

We got back to my car just before dark.

Grace

Grace, along with her husband Mike, had purchased a small plot of land deep in the woods near New Sweden, Maine because they couldn’t afford to buy anything in their home state of Pennsylvania. Their home was a 10’ x 12’ cabin that felt very solid and well thought-out, with a small cooking area that opened to a living area. A ladder led to a sleeping loft above.

I was very impressed by Grace’s story. She and Mike, both twenty-two years old, were determined to own their own home—somewhere, somehow—and live off whatever jobs they could find, however low paying. They had no interest in having any economic swing determine their home-owning destiny.

Grace was seven months pregnant, an eighteen-month-old girl toddling around her feet. She said that she and Mike wanted to add on another room when the baby came. Next to the cabin was a broken down trailer with three dogs inside barking nonstop; she said they used the dogs for hunting and protection. They’d shot a moose recently that had been hanging around literally just outside their door. The amount of meat was so overwhelming that they had to call in a neighbor (a dozen miles away) to help smoke and dry it.

Mike worked as a janitor in a church in a small town an hour away; Grace taught English in a community college in the same town on alternate days. Their place was neat as a pin. I asked about community, and she said there wasn’t much. I could feel her loneliness as well as her pride in what she and her husband had built. At least the place was warm and cozy, her baby fat-cheeked and healthy looking as she played with hand-carved toys. Their families had not approved of their decision to move away and start from nothing. The bible on the table was the only book I saw.

I asked if there was anything she would change, and she seemed to think hard about that one. She said she could do without the wood spiders—also known as giant crab spiders—that lived in the freshly cut wood they’d used in their ceiling. The spiders weren’t poisonous, but they were loud … evidently they liked the night time too, because that’s when they emerged from the ceiling, just inches from their heads where they slept, sometimes waking the whole family. Mike regretted his use of untreated wood, but since it was winter, he couldn’t do anything about it until spring.

Ethan

Ethan met me in the parking lot of a local restaurant near Presque Isle with his truck, his favorite goat Shelby riding shotgun in the front seat, and his dog Bananas in the back. I followed him in my car several miles on a dirt road into the woods until the road ended and we got out. He untethered three more sheep from inside a wooden shack, instructing me to follow him into the forest on foot. The sheep were very interested in my tires, licking at them and even biting them. He said they loved the salt and shooed them away.

Ethan told me he was twenty-one, but he looked even younger to me. Since he refused to eat, wear, or use anything he hadn't made (exceptions were his axe and gun), he wore only the garb he had hand-knitted: hat, sweater, baggy pants, and—he informed me—knitted underwear. He looked like a raggedy sort of elf.

After a mile or so of tramping through the woods on no discernible trail, we came upon a 10' x 8' log cabin, chinked with a strange white substance, that leaned seriously toward the east like a badly planned layer cake. Smoke curled out of a chimney made of dryer vent tubing, suggesting some sort of comfort inside, however it was 15 degrees outside in full sunshine and not much warmer inside the cabin.

He told me that during the day he hunted for game—deer, wild turkey, and moose (though he hadn’t come across one yet in the year he’d lived there)—dug for wild tubers, and shored up the chinks in the tiny log cabin he’d built by hand. At night, he read Thoreau, Kerouac, and John Muir by candlelight while wolves howled literally outside his door. In one breath he told me how much he loved this wild life he was living—that he had always wanted to be alone like this—and in the next he said he hoped his friends would want to join him someday, maybe set up a homestead on a neighboring piece of land.

I tried to pry from him the real reasons for being out there. I got out of him that he came from a wealthy family in Portland and his father was doing everything he could to convince Ethan to pack it up … telling his son he could have the best of both worlds: a really beautiful home—with heat and electricity—but also live far from other people. Ethan had insisted that his father was totally missing the point, which was to live as man had lived before modern conveniences in order to discover the essential self in the natural world.

I asked him if he ever got lonely. At first he said no, but then he admitted he sometimes did, revealing he liked to drive to the town library on Saturdays to check his email and to buy a weekly box of Cinnamon Poptarts.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

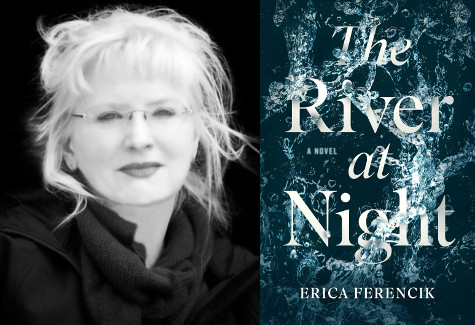

Erica Ferencik is a graduate of the MFA program in Creative Writing at Boston University. Her work has appeared in Salon and The Boston Globe, as well as on National Public Radio. Find out more on her website EricaFerencik.com and follow her on Twitter @EricaFerencik.