Now, these big time authors are being joined by the poet of skid row, the guy who’s always on the outside looking in, but who doesn’t actually want to go in, an author who crafted some of the darkest, most self-destructive narrators in American literary history.

David Goodis.

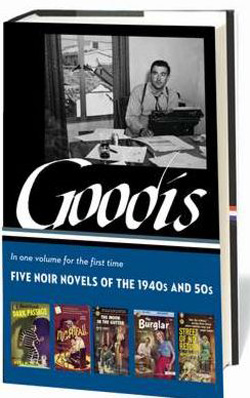

LoA has collected five Goodis novels (Dark Passage, Nightfall, The Burglar, The Moon in the Gutter, and Street of No Return) as their latest entry in what Newsweek called “the most important book-publishing project in our nation’s history.”

This is a significant milestone for Goodis’ legacy. One of the nation’s leading cultural institutions is recognizing him as one of the great American writers, worthy of standing on a bookshelf next to former presidents and Nobel Prize winners.

It’s a little surprising, even unsettling, to see Goodis getting the academic, highbrow treatment. My most cherished editions of Goodis’ work are the lurid paperbacks. Feeling the heft of the LoA volume and the thin, Bible-like paper, almost makes me think this is a big joke. Like the establishment is baiting Goodis and his legacy, only to snap it back and say it was all a big mistake.

But it’s not a mistake, or a joke, and LoA realizes what so many Goodis devotees have long known—there’s no one else quite like this mystery man from Philadelphia. The LoA praises Goodis for bringing “a jazzy, expressionist style and an almost hallucinatory intensity to his spare, passionate, uncompromising novels of mean streets and doomed people.” Hard to argue with that.

I would have liked to have seen Cassidy’s Girl in there, but this collection is a great starting point for anyone interested in Goodis. Dark Passage and Nightfall were two of Goodis’ most successful books, and they’re relatively cheerful compared to the darkness of the next three. By the time The Burglar came out in 1953, Goodis had already been broken by Hollywood, and his work became increasingly bleak. (I explored Goodis’ time in Hollywood in an earlier post.) The Burglar, The Moon in the Gutter and Street of No Return are classic examples of the tortured Goodis protagonist. These are guys so beaten down by life that they can barely rouse enough interest to be mad at the terrible things happening around and to them.

Goodis’ most famous novel Down There (filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player) is not in this volume because it appeared in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1950s alongside books by Patricia Highsmith, Jim Thompson, Charles Willeford and Chester Himes—none of whom have their own LoA volumes.

The Library of America has published other “genre” writers in the past. Philip K. Dick recently had three volumes devoted to his work. Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler each have their own volume, as do H.P. Lovecraft, Poe and Edgar Rice Burroughs. Hopefully the Goodis volume signifies not only a renewed appreciation of Goodis’ work, but also the willingness of the Library of America and other organizations to recognize the importance of noir writing in American literary history. This is a gorgeous book and it belongs on the shelves of every serious fan of crime fiction.

Richard Z. Santos lives outside of Austin and is enrolled in the MFA program at Texas State University. Once, he worked in Washington, DC, but now he doesn’t do much more than write and teach. He blogs at Paperclip People, and is working on his first novel—a crime thriller set in New Mexico.