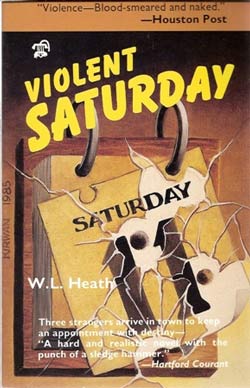

I n a previous Lost Classics of Noir column, I wrote about a book that is an example of its author doing a genre jump: writing in a vein that is something other than that for which he/she is generally known. Another intriguing type of novel is something I think of as a two-for-one, where the book is really of two different genres simultaneously. James Ross’s fine They Don’t Dance Much, for example, is both a work of Southern literary fiction and a noir story. W.L. Heath’s 1955 tale Violent Saturday has the exact same duality as the Ross book. It’s both a Southern social/literary novel and a crime story. And it’s excellent.

n a previous Lost Classics of Noir column, I wrote about a book that is an example of its author doing a genre jump: writing in a vein that is something other than that for which he/she is generally known. Another intriguing type of novel is something I think of as a two-for-one, where the book is really of two different genres simultaneously. James Ross’s fine They Don’t Dance Much, for example, is both a work of Southern literary fiction and a noir story. W.L. Heath’s 1955 tale Violent Saturday has the exact same duality as the Ross book. It’s both a Southern social/literary novel and a crime story. And it’s excellent.

Set in the town of Morgan, Alabama, not far from Birmingham, the story occurs over a single weekend in the summer. It’s an eventful couple of days in the generally quiet burg, because three men from Memphis have come to town to rob the local bank on Saturday afternoon. Heath’s set-up is perfect. He shows the cons doing all the prep work before they pull the job, and meanwhile, introduces the reader to many of the people who live in Morgan. In particular, his omniscient narrator gives us a peek into the lives of some of the individuals who will be forced into the fray of the crime scene. We come away with an understanding of just exactly who these citizens are, whose lives are about to be shaken up. And we’re seeing all this at the same time that we’re following the crooks as they get ready to pull the heist.

It’s fascinating to follow these two sets of things at the same time. And the mounting tension—as the clock ticks and these people go about their lives not knowing about the upheaval that’s about to take place around them—is bracing.

One of the more enjoyable characters in the book is a black man named Sugarfoot, who is the bellhop at the hotel where the robbers stay. Sugarfoot is an observer of people, one who prefers to have a nip from a bottle of something alcoholic in content as he makes his studies of persons and events. The following passage involves Sugarfoot, as the narrator describes the doings around Morgan on the Friday night before the fateful Saturday:

All around the little town street lamps had come on now, and people were walking home or sitting down to supper, or getting ready to go out to the movies. It was still hot, but at least it was night and the air was breathable again; and since this was the week-end eve there was there was a mild but general lifting of the spirits. At the drug store a group of high school boys were kidding around with a boothful of girls, and on the courthouse lawn some old men had started a checker game, sitting at the edge of the monument within the yellow oblong of light that fell from the band rostrum. Working men were taking showers, baby sitters were being phoned, canasta games were being played.

At the poolroom a round of snooker was shaping up. There were 4,700 people in the town of Morgan, and for almost every one of them Friday night meant a small but pleasant departure from the routine of weekday life. For some of them it meant choir practice at the Methodist church; for some it meant friends dropping in to watch TV; for some it meant nothing more than a quiet evening and a chance to read. But for Sugarfoot it meant just one more night like all the rest—if anything a little more tedious than the others. At eight o’clock he decided on another little pop.

Throughout the story, when we’re not following the thieves, we see how the Morgan folk think and live. Heath uses the characters to study the prevailing mindsets of small town Southern American people at the time. As an example, he has two of the characters—a married pair named Shelley and Helen Martin—discuss matters of race. Shelley will be very much a part of the robbery later this same day, but he doesn’t know this now, as he and his wife share their thoughts on black people:

Shelley sipped his coffee and shook his head. “I don’t know. We just don’t think of them as our equal. We can’t. It’s like it was something you’re born with. You can talk all you please about how you ought to treat them, but back in the back of your head you just don’t really believe it. There’s an instinct in a white man—at least a Southern white man—to not look on a Nigra as his equal. What you think and what you feel is two different things.”

“It’s a shame, too,” Helen said. “I try to be nice to them, but somehow it just goes against the grain to have one call me Helen instead of Mizz Martin.”

There’s a film version of Violent Saturday, which bears the same title as the book and was released in the same year. Victor Mature and Lee Marvin both excel in their roles as Shelley Martin and one of the robbers, respectively. But Ernest Borgnine seems out of his element in portraying an Amish farmer. Any film noir enthusiast would be likely get something out of the picture, although in my opinion it’s not quite a match for the book and is shy of worthy of being called a film noir classic.

There’s a film version of Violent Saturday, which bears the same title as the book and was released in the same year. Victor Mature and Lee Marvin both excel in their roles as Shelley Martin and one of the robbers, respectively. But Ernest Borgnine seems out of his element in portraying an Amish farmer. Any film noir enthusiast would be likely get something out of the picture, although in my opinion it’s not quite a match for the book and is shy of worthy of being called a film noir classic.

The novel Violent Saturday—which was reissued by Black Lizard in ’85, with an intro by Ed Gorman—backs up its title with some grisly scenes that occur around the bank job. It’s also an eye-opening social novel that lays bare the heart and soul of a small Southern town and its people. At moments, it’s an achingly tender story that studies the thoughts and feelings of people suffering from shock and grief.

Let’s close with a passage from the book that’s just a fine piece of writing. The scene involves a married couple named Boyd and Emily Fairchild. They are leading figures of Morgan’s social strata. Boyd is generally well-liked, but many townsfolk, particularly women, are put off by the promiscuous Emily. The Boyds, who are childless per Emily’s wishes—she doesn’t want to be tied down by the demands of motherhood—like to drink. And they tend to carry on pretty hard when they get to tipping the booze back. In the passage, it’s the morning of the bank robbery's Saturday, and they are both contending with hangovers after tying one on with some friends the night before:

She got up and walked to the window, peering through the Venetian blind. Boyd watched her, looking at her bare thighs beneath the pajama shirt, and again he felt a desire for her. She had always been more appealing to him at times like this. He wondered why. Something about the melancholy look she had. The tangled hair and the general air of dissolution. A thing like that appealed to a man at times. Like blues music, he thought, there’s something about it. Something sad and earthy and don’t-give-a-damn. Something low-down and at the same time beautiful.

Image of Opelika, Alabama via the Harper-Boyd Communicator

Brian Greene's articles on books, music, and film have appeared in 20 different publications since 2008. His writing on crime fiction has also been published Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, and Mulholland Books. Brian's collection of short stories, Make Me Go in Circles, will be published by All Classic Books in late 2013 or early '14. Brian lives in Durham, NC with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, and their cat Rita Lee. Follow Brian on Twitter @brianjoebrain.

See all posts by Brian Greene for Criminal Element.

Fine take on a novel I read many years ago, finally managed to snag the dvd recently. By the way, downloaded Death’s Sweet Song on your recomendation and enjoyed it. Very good noir.

I’m glad to hear you enjoyed these two pieces, and that Death’s Sweet Song worked for you!