While working on a friend’s music/culture magazine too many years ago, I once typeset a record review where the writer mentioned that the band under consideration never had pictures of themselves on any of the their album covers. He noted this in a praising way, the suggestion being that there was something cheesy about band photos on the covers. The music should speak for itself, he implied, and why not use the cover space for some kind of visually arresting, non-human image? I wasn’t sure I wholeheartedly agreed with this line of thinking–just so many great band photos on album covers that are so much a part of the album, really–but I had to admit that the band’s way of thinking, and the writer’s take on it, gave me cause to stop and reflect for a little.

While working on a friend’s music/culture magazine too many years ago, I once typeset a record review where the writer mentioned that the band under consideration never had pictures of themselves on any of the their album covers. He noted this in a praising way, the suggestion being that there was something cheesy about band photos on the covers. The music should speak for itself, he implied, and why not use the cover space for some kind of visually arresting, non-human image? I wasn’t sure I wholeheartedly agreed with this line of thinking–just so many great band photos on album covers that are so much a part of the album, really–but I had to admit that the band’s way of thinking, and the writer’s take on it, gave me cause to stop and reflect for a little.

It might be a stretch to make the following leap, but this comparison has occurred to me so I’m going to write it out: Derek Raymond, in authoring the four noir novels known as the Factory books, took this kind of anonymity-as-artful-technique a step further, by having the narrator and protagonist of those books be not only faceless, but nameless. Raymond, who along with Ted Lewis is considered by many to be the originator of the British school of hardboiled crime fiction, employed this method to great effect; his narrator not having a face you can visualize, or a name you can know him by, serves to evoke the kind of desolate atmosphere Raymond set to establish in the books. It works.

Many of the best noir novels feature an anti-hero in an uphill battle against society’s establishment forces. And while The Narrator is technically a part of the establishment, he fights his own bosses, and seeks to work against the grain of so much that is wrong with people and the world, thus is more anti-hero than he is “the man.”

Here’s The Narrator describing his unit and what others think of them:

The uniformed people don’t like us; nor does the Criminal Investigation department, nor does the Special Intelligence branch. We work on obscure, unimportant, apparently irrelevant deaths of people who don’t matter and who never did. We have the lowest budget, we’re last in line for allocations, and promotion is so slow that most of us never get past the rank of sergeant. . . . we spend our time looking in dead men’s faces, round their rooms, into the motives of their friends, if any, lovers and enemies.

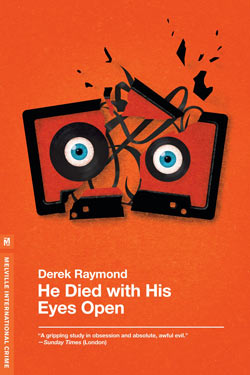

The case The Narrator works in the first of the Factory books, He Died With His Eyes Open (1984), is a typical job for him. A 51-year old ne’er-do-well named Charles Staniland is found savagely beaten to death (when The Narrator asks the police surgeon who performed the post-mortem what exactly Staniland died of, he gets the response, “Everything”). To the casual observer, Staniland was a nobody: a failed writer, failed husband, and a sot whom nobody liked, least of all the officers of the bank to which he owed a hefty sum on a series of loans they regretted having given him. Nobody from Scotland Yard is much interested in Staniland’s death, and none of them would care much if The Narrator merely mailed in an investigation with a tired lack of results. But, The Narrator being the kind of guy he is, that indifference to Staniland (not to mention the unimaginably sadistic way he was killed) makes him immediately interested in the case, and he goes to work.

The more The Narrator learns about Staniland – and he finds out much of this by way of some journal-entry like tape recordings the deceased left behind – the more sympathetic he becomes to the dead man. Staniland was a guy who just couldn’t get into a rhythm in life. He would make an excellent doomed lead character in a noir novel, and, in a way, he is just that in He Died With His Eyes Open. Staniland drank too much, talked too much, and was too intelligent a guy to be leading the existence he had: renting a council flat slum, drinking at pubs filled with ruffians, and driving a cab for a company owned by a greaseball. His last girlfriend was an emotionally frigid woman who psychologically abused him (not that he didn’t ask for that from her); the other punters at his local get so tired of hearing him run his mouth that they openly taunt him, beat him up, and finally tell him to find somewhere else to have his pints; his brother and sister-in-law would prefer not to hear from him; his boss at the taxi company has no time for him and the customers complain about him; the BBC, for whom Staniland worked for a stretch as an assistant script-writer, fire him when he can’t be satisfied cleaning up others’ teleplay copy but wants them to produce his own original works (which were brilliant and just “too good” for the BBC, one sympathetic former colleague tells The Narrator).

But through these conversations with people who knew Staniland, as well as in listening to the dead man’s shambolic recordings and perusing his similarly desperate writings, The Narrator sees something beyond the bothersome loser others considered the victim. The Narrator sees the man as a tortured soul who never got over the death of his young daughter. He finds in him a thoughtful, reflective man whose outlook was just “too good” for the world, in the same way that his writing was “too good” for the BBC. He was a guy who got down then just couldn’t help himself but keep digging in deeper, and whom others were only too happy to kick around as he lay there in the sludge. When that same friendly ex BBC co-worker tells The Narrator that Staniland, despite never having much money himself, once helped him out of a financial jam and never asked for any payback, The Narrator’s favorable impression of the damned Staniland appears solidified.

The following musings from The Narrator, uttered just after he has taken in another of Stanlinad’s confessional tape recordings, tells the story of how the detective-sergeant comes to feel about the case:

Mind, I had always asked it myself, but this why was not a copper’s why. Staninland’s question was the question I had once read on a country gravestone erected to a child of six: “Since I was so early done for, I wonder what I was begun for.

. . .

This fragile sweetness at the core of people –if we allowed that to be kicked, smashed and splintered, then we had no society at all of the kind I felt I had to uphold. I had committed my own sins against it, out of transient weakness.

But I hadn’t deliberately murdered it for its pitiful membrane of a little borrowed money, its short-lived protective shell – and that was why, as I drank some more beer and picked up the next of Staniland’s tapes, I knew I had to nail the killers.

Three more Factory books followed from Raymond, culminating with the series’ finale: 1990’s explosive I Was Dora Suarez, a book that some call the signature work of a noir godhead and others call vile. For me, this first installment of the Factory series was Raymond’s sharpest, and is a stone noir classic.

We’ll close with a scene that offers some rare chuckles in the otherwise austere novel. The Narrator is in search of Staniland’s last girlfriend, the one who tortured the man so. The detective-sergeant is having trouble finding the girl, but in his searches he does locate her ex-husband. The two get to talking over some drinks, and the guy (as well as his ex) turns out to be a colorful character with an amusing outlook on life and love and work and such:

Well, anyway, one day I arst her would she. Would she marry me, I mean. Christ, she went bleedin potty. You can stuff your bleedin marriage, she said, I don’t want no kids nor a mortgage or any of that crap. But we’ll have a good fuck (scuse me) if you like – I can’t think why you never arst me before, she said. Well, you could’ve knocked me flat. I’m a man who likes a charver if there ever was one, but my life, that put me right off – I couldn’t’ve got it up that time, not if she’d been Clordia Cardinal. Still, come to a rub, we did get married, and what a bleedin carve-up, as I say. I was on the buses in them days, the 137 route out of Clapham there. It got to be a nightmare with me, that job; once I knew she was carryin on with other fellers I started nearly missing stops wonderin what the hell was goin on at home and that – I ad to pack it in at the death. I said to myself, this as got to stop, Arthur, otherwise you are gointer go fucking barmy. So one night I just faced her with it, it was a Sunday, and you know what she said? Okay, okay, she said, keep your syrup on, I can’t think why you hung on this long. Well, I said to her, you really are just scum, Babsie, ain’t you? Ah, cut it out, she says, and with that she packs just one case of clothes an says you can keep all the rest of the gear, cunt, be seein you. It was hell the first few weeks she was gone; but then suddenly I woke up one morning feelin better, I don’t know why. So I got out of bed (I’d been spending a lot of time in the pit, mopin) ad a wash and a shave, went down to the local depot of the National Carriers, an got this job. I’d rather bore up the M1 with the radio on anyhow than grind round central London in a bus all day. Mind, I’m not sayin London Transport weren’t good employers, look after their people an such, but you get too many fights on the buses these days, specially at night. Anyway, come to a rub, I never looked back; I met my wife and we’ve got the two lovely kiddies an a house out Plumstead way. I just hear about Babsie from my mates now and then, like I said – but I never seen er again, not from that day to this, an that’s all I c’n tell you.

Read about more Lost Classics of Noir.

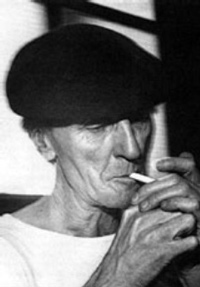

Image of author via Forgotten Classics.

Brian Greene's articles on books, music, and film have appeared in 20 different publications since 2008. His writing on crime fiction has also been published Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, and Mulholland Books. Brian's collection of short stories, Make Me Go in Cirlces, will be published by All Classic Books in late 2013 or early '14. Brian lives in Durham, NC with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, and their cat Rita Lee. Follow Brian on Twitter @brianjoebrain.

See all posts by Brian Greene for Criminal Element.

I Was Dora Suarez was the fourth book in the series, not the finale, although in many ways it feels like it. Dead Man Upright followed, and was a a disappointment in many ways–although not as a window into the author’s mind. As the series progresses, the reader realizes more and more that the narrative may exist only in the nameless detective’s own head. Or at least that he is shaping events after the fact. The first four books in the series are essential reading, although Suarez is certainly gut-wrenching. In his autobiography, The Hidden Files, Raymond (real name Robin Cook) says, “SUAREZ was my atonement for fifty years’ indifference to the miserable state of this world; it was a terrible journey through my own guilt, and through the guilt of others.” Not exactly light reading–and no wonder that the author called these “black novels”.

Thanks for the correction! Didn’t realize about the fifth book in the series. Interesting thoughts here. One thing Raymond/Cook wrote, that I’ve always valued, is his intro to one of the editions of Ted Lewis’s brilliant GBH.