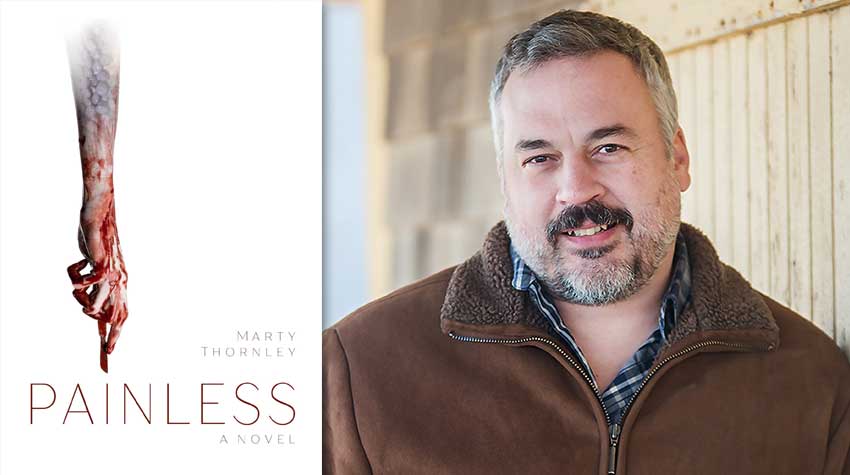

On Process: Screenplay vs. Novel

By Marty Thornley

January 9, 2019

While they may share the end goal of “telling a story,” a novel and a screenplay are two very different products, each with its own requirements, approaches, and styles. The most significant difference is that a novel is a finished product, while a screenplay is a blueprint for a film that might get made one day. I spent close to 15 years thinking about and writing screenplays. The last one I ever wrote was called Painless. About a decade after I had moved on from the film industry, I realized I had not written anything in way too long. I didn’t have any interest in chasing the movie dragon anymore, so I decided to turn Painless into a novel. That should be easy!

Ok. So it did not turn out to be easy, but I did find it enjoyable. The plot changed very little, but the world and the characters and the meaning of everything expanded far beyond what had been in the original screenplay. It was like I was watching the film finally get made and fleshing out the things a script can only hint at.

Rules and Limitations of a Screenplay

There are some pretty strict restraints on what can and cannot go into a screenplay. The simple reason is that it is first and foremost a blueprint, a tool that needs to be read and understood by an army of people. Everyone from producers to directors to actors to the costume designers needs to read and analyze the script, so it has strict formatting rules. Those are easy enough to follow with screenwriting software.

The more difficult requirements concern what words you are actually allowed to include, how many of them there can be, what font and size you can use, and even what tense you can use. Sounds fun, right? Let’s dig into that a little. But first, I will make the usual disclaimer that while there are always exceptions to the rules. The following are pretty much standard for anyone writing a screenplay and hoping that it will get bought and made.

Tense and Point-of-View

You can ONLY write in third-person, present-tense. It needs to read as if you are watching a movie. No matter when the story takes place, the act of watching is happening in the present, so that is how we see it, so that is how the script reads.

Joe walks into the bar.

Show Me. Don’t Tell Me

You cannot describe smells, or tastes, or the feel of anything. A character can comment on something, but that would be dialogue. The reason I did not call the POV limited or omniscient earlier is that you can NEVER describe ANY character’s interior thoughts or dialogue. (Again, I am using broad strokes here, but this one is pretty important.) Why? Because none of that will EVER be on the screen. You have to imply things. Is Joe nervous? You cannot say that. But you could say:

Joe walks hesitantly into the bar, his hands fidgeting at his sides.

Know How the Page Count Works

Screenplays are assumed to be one page per minute of screen time. A 120-page script would be about 120 minutes. So you can instantly look at the page count and know if it is appropriate for the genre. Horror or goofball comedy? That better be about 90-100. Epic period piece? More like 120. Did you just hand someone a 60-page script? That is not enough material for any realistic project, and they immediately know you don’t know what you are doing. Same for anything over 120. If you are a nobody and passing around your 150-page space opera, no one is going to read that.

Know How the Page Count Works (Part 2)

Let’s stick with the 120-page example because the math works better. Within that strict page count, there are some other numbers to remember. 10. If you don’t have a reader hooked by page 10, it is going in the trash. 30. Approximately 30 minutes into any film (the good ones, anyway), there is a turning point that really kicks the story into gear. Star Wars: A New Hope. What happens 30 minutes in, almost to the second? Luke returns home to find his aunt and uncle killed. Now, he is forced to go on his quest. 60. Halfway through the screenplay is a midpoint where everything shifts again. 90. A major event heading us into the climax.

The Relative Freedom of the Novel

How many pages does a novel have to be? Kind of a trick question, right? There are many accepted ranges based on genre, but those ranges vary a lot. The Great Gatsby is only 47k words. Some of the Game of Thrones books top 450k. Of course, there are some standards around being an aspiring genre writer, so I was aiming at 80k for Painless, and it ended up at 75k. But I really didn’t worry too much about that as I wrote. I seemed to be on pace and that was it.

I had already structured the story like a film, so I didn’t have to worry about that either. All that was left was describing each scene in ways I could not in the script and getting into the characters’ heads.

This is where it got interesting for Painless. As a movie, the audience would be watching all this gruesome, bloody action and wondering what the characters might be thinking. I thought that could be an effective, creepy thing to watch. In book form, there are no visuals, but you get to see all the action from inside the heads of each character. A few scenes that were one or two lines of action in the screenplay became four or five pages of inner monologue.

Visual Storytelling

I’ve been asked several times if a background in screenwriting makes my prose style more visual. As far as my writing style, I would have to say it is very much the opposite. Screenplays provide such little room for detail, leaving a director and crew to fill out visuals later. So my writing tends to be very short at times and relies on the reader to do some work to figure things out.

I do, however, speak in images, hoping that a reader will see what I am seeing and infer the same hidden ideas between the lines. I also repeat imagery from time to time, hoping that the callback will be a visual memory with the reader that draws some kind of thematic parallel between scenes.

At the end of the day, it’s all about telling a story and getting an audience to connect with it. I’ll leave you with this: Go watch Vertigo, directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Is that last shot more or less powerful because we have no idea what Scottie (played by James Stewart) is thinking? If you think you know what he is thinking, it is because you are projecting your own thoughts into his head due to that image and everything that led up to it. That is visual storytelling.

Comments are closed.

You may be somewhat a rare bird. Most who write screenplays seem to begin life as short-story and long-form fiction writers. You took the opposite path. So your words are comforting to me. And you obviously can write well, as evidenced here.

I’ve been struggling as a novelist with all of the ‘rules’. But even advice on how to write novels often comes from ‘experts’ who have not discriminated between what should be done to write screenplays and what should be done to write novels. I think their minds have been poisoned.

What Robert McKee says is absolutely legitimate, for instance. But not that much of what he says applies to writing long-form fiction. His focus is the screen. Professor Google often conflates those legit ideas with what fiction writing actually does need. It borders on the criminal for them to be that stupid.