“How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child!”

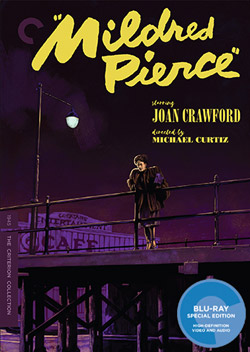

That oft-cited sentence from Shakespeare’s King Lear would have been well placed on an opening page of James M. Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce and just after the opening credits on Michael Curtiz’s 1945 same-named film adaptation of the story. Criterion Collection has just released a new Blu-Ray version of Curtiz’s movie, and that gives me an excuse to write about it—as well as the Cain book—and to think about the Shakespeare quote while considering both.

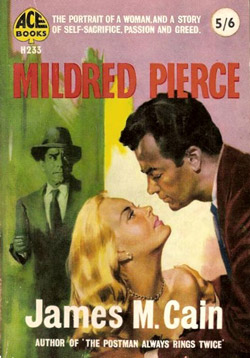

The book was the 3rd published novel from the hardboiled crime fiction leading light Cain, whose works The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) and Double Indemnity (1943)—among others—were also adapted for notable films noir. Curtiz’s career as a movie director was too lengthy for me to try and sum it up in a sentence or two, so I’ll just mention that he was also the auteur behind the camera on Casablanca (1943) and one of my personal favorite Elvis movies, King Creole (1958).

For Joan Crawford, the title character and biggest star of the Mildred Pierce movie, this role (which brought her an Oscar) represented a new artistic blossoming, as it was the second feature she starred in after signing a contract with Warner Brothers in the wake of a long run of work for MGM coming to an end by mutual consent. Curtiz didn’t want Crawford for the role of Mildred Pierce, but when first choices Bette Davis and Barbara Stanwyck didn’t work out—and when Curtiz had to reluctantly admit that Crawford was convincing in her reading for the part—she got the gig. It seems tensions between director and star were often high on the set.

For Joan Crawford, the title character and biggest star of the Mildred Pierce movie, this role (which brought her an Oscar) represented a new artistic blossoming, as it was the second feature she starred in after signing a contract with Warner Brothers in the wake of a long run of work for MGM coming to an end by mutual consent. Curtiz didn’t want Crawford for the role of Mildred Pierce, but when first choices Bette Davis and Barbara Stanwyck didn’t work out—and when Curtiz had to reluctantly admit that Crawford was convincing in her reading for the part—she got the gig. It seems tensions between director and star were often high on the set.

It’s hard to imagine that many reading this aren’t already familiar with the storyline of Mildred Pierce, but for the sake of conversation and to set up what I’m going to say below, let’s revisit the basics of the tale. Set mostly in Glendale, California, the story takes place through the decade of the 1930s in the novel and over the early part of the ‘40s in the film. The titular character is a woman (meant to be about 30 at the opening?) who, at the outset, is a middleclass homemaker who’s married with two young daughters. Her husband, a former real-estate man, was put out of work by the Great Depression and a conniving, opportunistic former business partner (who also happens to have the hots for Mildred). Unemployment has caused Mr. Pierce to become shiftless and sent him towards what some would call a downward moral slide; he’s lying around a lot and having a fling with a local hussy. Mildred, onto his affair, tells him to leave their home. She will raise their two girls on her own.

There are two major challenges facing Mildred as she sets about being a single mother trying to keep a roof over the head of herself and her two daughters and food on their table. First, she has to find a way to earn money—and a lot more of it than she’s been making by selling homemade pies to neighbors. She has to get a job. But she has no work experience, and jobs aren’t exactly plentiful at the moment.

Her other big problem is her oldest child, a teenager named Veda. Here’s where the King Lear quote becomes relevant. Veda has high-society airs that are out of line with the modest lifestyle of the Pierce family—and certainly not in synch with the kind of life they’re likely to lead with Mildred as sole breadwinner. Veda is a snob and a brat. Yet, while most of us would roll our eyes at the girl after listening to her carry on for few minutes, Mildred is her mother. And, she has an abnormally strong attachment to Veda, even for a mom in relation to her child.

I’m not ruining the story for anyone who doesn’t know it by saying that Mildred—who’s always been good with food preparation and service—first finds work as a waitress, then goes on to open a highly successful restaurant of her own. But things get interesting when she becomes romantically entangled with a socialite playboy who likes the finer things in life but wouldn’t dream of working to earn any of them. When this man gets to know Veda, who is of course dazzled by him, Mildred better watch out.

Now that we’re all caught up, let’s compare the two: there are differences, both major and minor, between book and film. Some of those I won’t mention here, so as not to spoil the story for those new to novel and/or movie. But I can say that, as alluded to above, in Cain’s book the storyline takes place over 10 years, while the movie only spans four. Also, the novel is told by an omniscient narrator, while the film is partly narrated in voice-overs by Crawford as Pierce. The book runs in chronological order, while the movie flips back and forth between past and present.

Now that we’re all caught up, let’s compare the two: there are differences, both major and minor, between book and film. Some of those I won’t mention here, so as not to spoil the story for those new to novel and/or movie. But I can say that, as alluded to above, in Cain’s book the storyline takes place over 10 years, while the movie only spans four. Also, the novel is told by an omniscient narrator, while the film is partly narrated in voice-overs by Crawford as Pierce. The book runs in chronological order, while the movie flips back and forth between past and present.

Something that might make noir heads appreciate the written version more than the screen one is that the former is tougher in places. For instance, in the opening scene, when Mildred tells her hubby to take a hike, in Cain’s book she threatens him with a meat cleaver if he won’t vacate—a length the character does not go to in the movie. Likewise, there’s a famous scene in the film in which Mildred gives Veda a pop across the face to put her daughter in her place (good luck with that) after Veda has gone on one of her snide, insulting rampages; in Cain’s book, Mildred slaps Veda several times, then gives her an over-the-knee spanking.

Having just given Cain’s novel a fresh read over the same span of time during which I re-watched the movie and digested the extras on the Criterion disc, I have to say that, overall, I think Curtiz’s adaptation (aided by the screenwriting effort of Ranald MacDougall) puts the story across more effectively than does Cain’s text. Of course, Cain is considered a master of hardboiled crime fiction, and, of course, the movie wouldn’t have been possible without the book. But at the risk of committing literary criticism sacrilege by griping about the work of a recognized master over this visit with Mildred Pierce, I found the novel to be over-written in many places and often a labor to read.

There are passages that don’t add a lot to the story and are a grind to get through, and other segments that are needed but could have been a lot shorter without excluding anything that helps the tale move along. And there are many places in which Cain spends too much time telling us about the characters’ motivations instead of just setting the scenes, showing us what they do, and letting us figure out for ourselves what they’re thinking and feeling.

Having said all that, I should stand up for the novel in comparison to the film in a few respects—namely that it contains a key character (a world-wise neighbor friend of Mildred’s) not included in the screen version, and that, in the book, Mildred’s feelings about Veda are more psychologically complex than how they come across in the screen adaptation.

As always with Criterion releases, the extras that come on the disc are a whole world within themselves that help you see the movie in deeper ways. The Mildred Pierce bonus features include: a 2016 chat between film/literary critics Molly Haskell and Robert Polito in which they analyze the movie and Cain’s novel while discussing the similarities and differences between the two; a clip from the Today Show in 1969, which shows Hugh Downs interviewing Cain about his literary work, the state of the novel in general, and an assortment of other subjects ranging from the war in Vietnam to marijuana to the mindset of the youth of the day; a 2006 stage interview between noir historian Eddie Muller and Ann Blyth (co-star who played Veda) at a screening of Mildred Pierce—this is the least enjoyable of the extras, as Blyth’s responses to Muller’s questions are generally pat and un-illuminating; an excerpt of The David Frost Show from 1970, in which Frost interviews Crawford, who comes off as batshit crazy, drunk, or both while discussing Mildred Pierce, her acting career in general, and, um, things like what a person needs to have in his or her life to keep from needing psychological care; a feature-length documentary on Crawford (have to confess I haven’t had a chance to take this in yet); and a booklet essay by critic Imogen Sara Smith.

As always with Criterion releases, the extras that come on the disc are a whole world within themselves that help you see the movie in deeper ways. The Mildred Pierce bonus features include: a 2016 chat between film/literary critics Molly Haskell and Robert Polito in which they analyze the movie and Cain’s novel while discussing the similarities and differences between the two; a clip from the Today Show in 1969, which shows Hugh Downs interviewing Cain about his literary work, the state of the novel in general, and an assortment of other subjects ranging from the war in Vietnam to marijuana to the mindset of the youth of the day; a 2006 stage interview between noir historian Eddie Muller and Ann Blyth (co-star who played Veda) at a screening of Mildred Pierce—this is the least enjoyable of the extras, as Blyth’s responses to Muller’s questions are generally pat and un-illuminating; an excerpt of The David Frost Show from 1970, in which Frost interviews Crawford, who comes off as batshit crazy, drunk, or both while discussing Mildred Pierce, her acting career in general, and, um, things like what a person needs to have in his or her life to keep from needing psychological care; a feature-length documentary on Crawford (have to confess I haven’t had a chance to take this in yet); and a booklet essay by critic Imogen Sara Smith.

The story on Crawford’s reception of her Oscar for Best Actress in a Leading Role in Mildred Pierce is one that contains controversy and often evokes snickers. The diva didn’t show up for the ceremony and wound up receiving the hardware at home, in bed, surrounded by members of the press. She said she was too ill to leave her house that day, but her detractors say she blew off the ceremony because she didn’t expect to win and didn’t want to have to sit there and take it in front of everybody when another candidate got the trophy and the love. She repeats the (hard to swallow) anecdote about her illness on that day in the above-referenced interview with David Frost. Also over that chat, she tells Frost that Mildred Pierce is the role of which she was the most proud to have scored. Whatever the deal really was on Oscar night, she deserved the award, as she is dynamite in the film.

She wasn’t the only one who got nominated for an Oscar for their work on the feature. Ann Blyth and Eve Arden (who plays a wise-cracking friend of Mildred’s who takes on some of the traits from the missing character from Cain’s book) each got shortlisted for their work as supporting actresses. MacDougall got a nomination for his screenplay, and producer Jerry Wald and cinematographer Ernest Haller were also on the academy’s shortlist. Zachary Scott (the smooth and snide playboy) and Jack Carson (the conniving and opportunistic ex-business partner of Mildred’s husband) didn’t get nominated for Oscars, but both are fantastic at their parts.

In the opening to this post, I made it sound like an ungrateful child’s poor treatment of its parent is the most crucial aspect of Mildred Pierce. But while Veda’s impossible ways and Mildred’s difficulties in handling her are all certainly driving forces behind both Cain’s novel and Curtiz’s film, the real moral and most core theme of the story is nicely encapsulated by Smith in her write-up in the Criterion booklet. She calls the tale “an acute, unsparing study of relationships poisoned by class and money.” Nailed it.

It’s an indictment on the American Dream, really. It reveals the barriers inherent in the country’s social stratification pecking order and studies the walls those of the working class are likely to run into when they find themselves side by side with those born into the upper crust. And if you want to get more specific, you could say that the story looks particularly at the challenges of a woman who tries to lead her family into moneyed social advancement in this era. Veda’s teeth aren’t the only ones who turn serpent-like on Mildred.

See also: Page to Screen: The Harder They Come

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and reviews and articles of/on books, music, and film. His work has appeared in 25+ publications since 2008. His pieces on crime fiction have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, The Life Sentence, Stark House Press, and Mulholland Books. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina.

His writing blog can be found at: http://briangreenewriter.blogspot.com. Follow Brian on Twitter @greenes_circles

Thanks for this. Nicely done. And I agree, especially with the comments about the novel. Cain could’ve used a shrewd editor. And thanks for mentioning Zachary Scott, a wonderfully talented actor who could’ve been a major star (and given Cary Grant a run for his money in the suave department), but when you die of a brain tumor at 51, you’re deprived of a long career that could’ve produced more irconic movies. I think he’s one of the most underrate actors in film history.

Richard, thanks for the comments. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. And I agree with you on Scott.

I wanted to leave a little comment to support you and wish you a good continuation. Wishing you the best of luck for all your blogging efforts.

I’m most certainly bookmarking this site and offering it to my associates. You will get a lot of guests to your site from me!

Music began playing any time I opened this website, so frustrating!