“The modern detective story and the modern Western have a great deal in common. . . .In essence both kinds of stories are American products, like corn on the cob and blueberry pie.” – Erle Stanley Gardner, “Introduction” to Davis Dresser’s The Hangmen of Sleepy Valley.

John Wayne never said “A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do.” What he said in Stagecoach was, “There’s some things a man just can’t run away from.” And what he said in Hondo was, “A man ought to do what he thinks is best.”

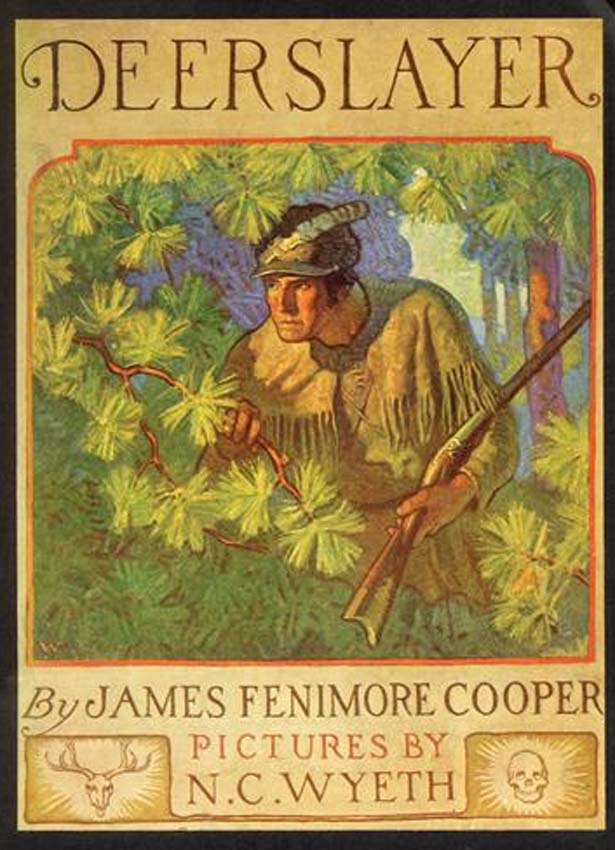

Wayne would have understood the sentiment, however, and so would just about every other masculine hero from the time of Achilles right up to Spenser and beyond. Let’s not go all the way back to Achilles, however. Since I’m going to talk about the similarity of the western hero to the private-eye, let’s just go back to the original American hero, Natty Bumppo, the hero of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking series.

Here’s another thing. How many married western heroes or private-eyes can you think of? Oh, sure, there are a few, but most of them are loners. Natty Bumppo knew that those who travel fastest go alone. In The Deerslayer, when he’s offered the choice between marriage and torture and death, he doesn’t hesitate to choose the latter option. And when a beautiful woman

So what about the law? The hero doesn’t let the law determine his behavior, whether it’s in the old west or the new west. In refusing to go on a scalping expedition, even though scalping is perfectly legal and in fact rewarded by the colony, Natty Bumppo said that the law itself is unlawful, “and ought not to be followed.” A lot of western heroes are lawmen, but think about those who work a bit outside the law. I’ve already mentioned Zorro. A lot of private-eyes do follow the law, but like Mike Hammer, they don’t mind fiddling with it or using it in ways the police don’t consider appropriate.

We all know the western hero is a square shooter, or, as Natty puts it, “I would dare to speak the truth consarin’ you or any other man who ever lived.” The private-eye might lie to a criminal and prevaricate to the cops, but it’s the truth he’s always after. Or maybe the Truth, and he’s going to find it and speak it by the end of the novel, no matter what. The truth and the finding of it are what the books are all about.

Of course there are a lot more similarities between the private-eye novel and the western, and between all crime novels and westerns, for that matter. After all, aren’t western novels really crime novels? The crimes might be different, but they’re crimes all the same. And of course some crime writers are also well known for their westerns. The names Ed Gorman and Loren D. Estleman come immediately to mind.

I look forward to your comments. There’s a lot more to be said about the relationship of the western to the crime novel, and I hope to continue the discussion.

Bill Crider is a Texas writer, author of the Sheriff Dan Rhodes series, fan of the Kingston Trio, and a collector of baseball cards.

You make a strong case for the private eye genre as an out-growth of the western genre. Strong, independent men with a deep sense of Justice are common to both.

And who doesn’t romanticize a sharp-shooting handsome loner? Though I wouldn’t fantasize about marrying this type. The reason why women swoon over these guys is because they ain’t no pram pusher!

And maybe the western hero is an outgrowth of the classic knight errant, as I’ve heard some say? All these kind of characters have lasting appeal to me because they embody personal justice in action, not an impersonal system’s compromises. That they’re frequently loners and flawed themselves just makes them more fascinating instruments.

Good stuff, Bill.

Oddly enough, it reminds me of something I’ve never actually read. Robert B. Parker wrote his dissertation on, I believe, this exact topic. It was titled, “The Violent Hero, Wilderness Heritage and Urban Reality” and traced the private eye genre to Cooper. Have you read it? If so, do you know where it can be obtained?

At first I was also going to add that every white hero has to have an ethnic sidekick, too. Then I thought how the Theme has evolved. Have you seen the latest Hawaii Five-O? The two white guys are the Bickersons. (“It’s my car, and you won’t even let me drive it?”) And the two ethnic sidekicks don’t even get to ride in the back seat. They just stand around … waiting to get a line in now and again.

Good stuff. I had never thought about the two heroes being so similar. Right there in my face though, now that you’ve pointed it out.

Always like to see this subjecft discussed, Bill. You didn’t mention your own experiences with both genres. as well as Bill Pronzini and James Reasoner. Otherwise, nice job.

RJR

Hmmm. Bill C. is well trench-coated to write about it, isnt he? Stay tuned!

John Wayne never said, “Geddoff yer horse and drink yer milk,” either but I can see Bogie saying something similar. Minus the horse of course. And perhaps the milk. But I can hear the lisp and sardonic turn of phrase. P.I.s and cowboys. Twins seperated at birth. And don’t forget Pea Eye was a character in Lonesome Dove. Nuff said.

Well, you are right as far as mainstream genre western/crime novel formula novels go. The average reader goes back to the genre novels again and again to vicariously achieve justice. As Owen Ulph wrote in his essay on the meaning of the word, “maverick,”

“Present-day existence is hopelessly schizoid. Nobody really loves Big Brother, and inside the most timorous conformist a smothered rebel cringes in fear. The discrepancy between our ideals and daily realities is manifest in the fascination with which even intelligent people view western fantasies depicting the achievement of social justice by maverick heroes who ride roughshod over all obstacles and ‘put things right,’ and the silent despair most of us suffer at the shoddy compromises and degrading sell-outs we incessantly endure.”

But the categories of westerns and crime novels encompass so much more. Fortunately the genres have subgenres which feature social and historical criticism and occasionally even tackle the big issues: life, death, the nature of man and the meaning of existence.

Such books as Oakley Hall’s WARLOCK and John Williams’ BUTCHER’S CROSSING don’t fit the formula and may not be held in high regard by the book chains, but we all grateful that such books can also be called “westerns.”

Parker’s dissertation was published, after a fashion, by the microfilm division of Xerox, I believe, in 1974; I just requested a copy through interlibrary loan. Bill’s conflation of the two genres is very thoughtful and considered, and a useful way to think about both; and going back further, as clare2e notes, it is no accident that some PIs and similar characters (Simon Templar and Travis McGee, neither of whom was an official PI but who were very much of that world, to name only two–not to mention Philip Marlowe, whom Raymond Chandler put explicitly in that tradition) are thought of as modern knights-errant.

Thnaks for Shaering it