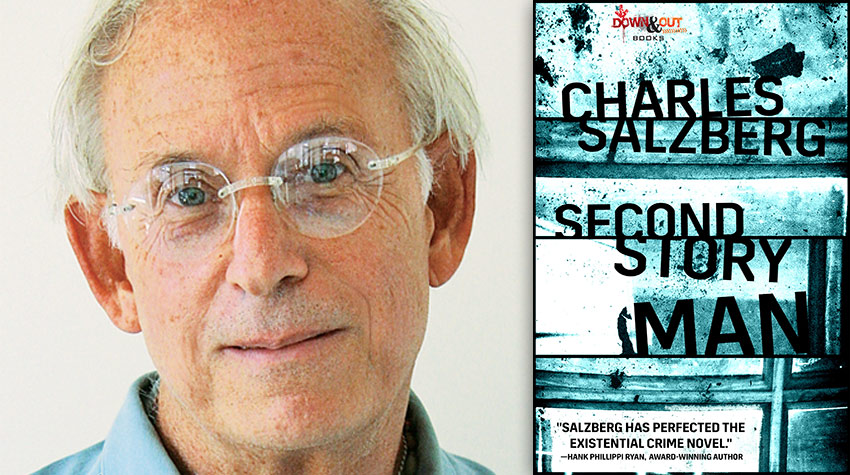

Q&A with Charles Salzberg, Author of Second Story Man

Charles Salzberg is a former magazine journalist who recently turned to a life of crime—fictitiously, of course. His acclaimed Swann series boasts four titles (with a fifth on the way); these include Swann’s Last Song, which was nominated for a Shamus Award, and Swann’s Lake of Despair, which was nominated for two Silver Falchions and was a Finalist for the Beverly Hills Book Award and the Indie Excellence Award. His novel Devil in the Hole was named one of the best crime novels of 2013 by Suspense Magazine, and his novella “Twist of Fate” was included in Triple Shot, a collection of three noir crime novellas. Salzberg—who teaches writing at the New York Writers Workshop, where he is a Founding Member—has also written more than 20 non-fiction titles. His most recent novel, Second Story Man, takes inspiration from real-life thievery and obsession.

Recently, the author kindly entertained curiosities pertaining to branching out from the Swann series, melding fact and fiction, and creating suspense through the use of multiple perspectives. Salzberg also discussed his background in journalism, the realities of teaching writing, and what comes next in his storied career.

Second Story Man marks a departure from your Swann series. What was the impetus for writing this book, and how did the crime genre lend itself to an exploration of existentialism?

Having just finished Swann’s Way Out, I thought I’d written the last Swann novel—that I’d taken the character as far as I could. And so, I was looking for something else I could sink my teeth into. Years ago, I read a piece in The New Yorker that stuck in my mind. It was about a master burglar known as The Silver Thief. I went back and re-read it—it held up beautifully—and I got to thinking about the need to be the best at something. How it seems to be a very American thing. We make everything into a competition, and the prevailing attitude seems to be to win at any cost. To be a loser is to be a failure. We have a president now who’s all about winning and who disdains “losers.”

This bothered me, and after reading about The Silver Thief, I realized it was possible to write something in terms of crime about this obsession. I began researching burglary and came across another thief known as the “Dinnertime Bandit,” who only struck when he knew his victims (and their valuables) would be home. Like the Silver Thief, this guy considered himself the best ever. I had my story.

Using facets of both these men, plus a few others, I created Francis Hoyt—arrogant, athletic, brilliant, someone who thought of himself as the best and who was willing to do anything to maintain that status. Then, I created two men on the other side, who also considered themselves the best at what they did.

That provided me with the conflict I needed.

As far as being existential, I suppose in this case it means the novel is really a consideration of what it means to be a winner (does this sound familiar) and what the costs are. The existential question is: how far will one go to be a winner and at what cost?

Francis Hoyt’s character is drawn upon two real-life burglars: the Dinnertime Bandit and The Silver Thief. How did fact inform your fiction, and what was the role of creative license in crafting an antagonist who is both familiar and original?

Francis Hoyt’s character is drawn upon two real-life burglars: the Dinnertime Bandit and The Silver Thief. How did fact inform your fiction, and what was the role of creative license in crafting an antagonist who is both familiar and original?

We all know that line about life being stranger than fiction, and it’s often true. Since I know virtually nothing about being a thief, I had to do a lot of research. I also had to come up with a flesh-and-blood character, which meant I had to get into the mind of a master thief, giving him a past as well as a present. In the novel, I used some of the facts when it comes to the various break-ins—for instance, it’s true the thief hit several houses one night right under the noses of the cops who’d staked out the neighborhood. But as far as Francis Hoyt is concerned, he’s totally a product of my imagination. The same is true of the two men who are after him: Charlie Floyd, a recently retired Connecticut State investigator, and Manny Perez, a Cuban-American Miami police detective. Both these characters were slightly familiar to me since Floyd was a major character in my novel, Devil in the Hole, while Perez appeared briefly in one chapter. They were both interesting enough to me to want to use them again, and so I did. I think they make an odd pair because they’re so different yet share an obsession with doing their job well.

The book alternates perspectives between Hoyt and the two lawmen tasked with catching him. How does this construct heighten the overall narrative suspense, and in what ways do the dueling viewpoints allow for organic character development?

It’s a technique I used in Devil in the Hole but to a much greater extent. Doing it this way allows me to get into the heads of all three of the men while heightening the suspense at the same time because we see the story from the three perspectives. The reader knows what all three are thinking, while each of them only knows what he’s thinking. But it doesn’t work unless each chapter moves the story forward. It’s not like Rashomon, wherein each character is telling the same story only from a different point of view. I tried to make it so that no information is repeated.

You have a background in journalism. Can you briefly compare/contrast the standards of non-fiction and fiction? Also, in what ways has that lineage lent itself to your creative writing endeavors, both in terms of process and storytelling?

I wanted to be a novelist well before I ever got into journalism. In fact, becoming a journalist was an accident. I thought I wanted to be a magazine editor and so I got a job in the mailroom at New York magazine. But when I saw what editors did as opposed to what writers did, I realized writing was for me. I’d never written a magazine article, but I approached it as I would a piece of fiction. I realized that no matter what I was writing, it was all about story. And so, being a fiction writer, I’d already mastered a lot of the techniques: creating a scene, using dialogue, telling a coherent story with a point of view.

Writing nonfiction made me a better fiction writer. Having to work to a word count was invaluable. It taught me the necessity of making every word count, thereby cutting down on a lot of wasted verbiage. It also taught me how important it was to get and keep the reader’s attention as well as how important character and dialogue was to a successful article.

Any kind of writing you do—whether it’s fiction, nonfiction, poetry, advertising writing—must tell a story. It has to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Working as a journalist helped me to understand that.

Being a journalist also taught me how to research and how to interview people. These skills come in handy with everything I write. For instance, every one of the Swann novels introduces the reader to other worlds: the art world, the world of rare books, the movie industry, the world of photography.

You also teach writing. In your opinion, what of the discipline can be learned versus what is intrinsic, and how does tenacity factor into the equation?

I’ve learned I can help someone become a better writer, but I can’t teach someone how to write. As far as I’m concerned, it’s an innate skill. There are people who are natural storytellers and others who can’t tell a story to save their life. For instance, let’s say I tell a joke to someone who’s a good storyteller. When that person retells the story, chances are it’s going to be even better. But if I tell that joke to someone who can’t tell a story, it’s going to come out a jumble when they try to retell it. Why? Because some people have a better storytelling sense than others. I think you can teach organizational skills and the skill of being able to look at what you’ve written, see where there are problems, and improve those areas, but either you’ve got talent, or you don’t. I, or any other teacher, can’t give it to you.

I think you’ve hit on one of the most important things about being a writer, or any kind of artist: tenacity. There’s so much failure in what we do, and if you’re going to make it, you have to be able to shrug off that failure, learn from it (if you can), and go right back at it. When I was starting out, if I got a rejection, I wouldn’t sulk about it—and believe me, it hurt—I’d just send that piece of writing out to two more places and keep doing it until it sold or I’d exhausted every possibility. You have to believe you’re good enough to get published. If you’re not tenacious, then you’re not meant to be a writer.

Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

I thought I’d written the last Swann, but a year after I finished Swann’s Way Out, I came up with another idea, another place to take the character, so I’m in the middle of writing Swann’s Down. In September, we have a sequel to Triple Shot, the collection of three crime novellas I contributed to along with my friends Ross Klavan and Tim O’Mara. This one’s called Strike Three. Also, I’ve started another novel with a new PI, and I’m actually thinking of writing a spin-off of Second Story Man.

Comments are closed.

Thnaks for Shaering it

I was particularly impressed by the incorporation of real-life case studies, which brought the topic to life and helped me grasp the challenges faced by individuals with schizophrenia. The inclusion of current research and up-to-date statistics further enriched the essay’s credibility.