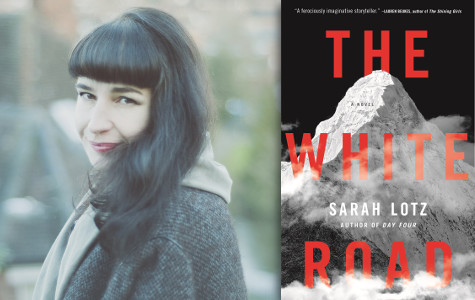

Sarah Lotz is a novelist and screenwriter who carries a self-professed affection for the dark side. Her books include The Three and Day Four—both of which Stephen King heartily endorsed. Lotz’s newest, The White Road (available May 30, 2017), is published by Mulholland Books and has earned a starred review from Publishers Weekly. The author, who drew upon her knowledge of extreme sports to amplify that work, lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

Recently, Ms. Lotz generously made time to reflect on the varied elements that enhance her “genre-bending” stories.

The White Road’s opening line is a real attention grabber. What is the importance of making that first impression on a reader, and how do you endeavor to do so?

Thank you! The first line is a useful tool to grab a reader’s interest, but it’s pointless making the opening sentence a cracker if the rest of the novel a damp squib. That said, I rewrote that line over fifty times! The rest of the novel ran to over twenty drafts, and like all writers, I could have gone on if I hadn’t been wrestled away from the computer. But you have to stop somewhere.

Place is integral to your plot. In what ways do you think that setting becomes its own character within the story, and how did your experiences with cave diving and climbing Everest inform the narrative?

I actually wrote the scene where Simon, the narrator, ventures into a cave in the Welsh countryside before I went caving. Thank god I didn’t leave it at that—in the first draft, I stupidly had Simon endlessly commenting on the cave’s damp, cloying smell and panicking about how dark it was.

I will be forever grateful to the generous folk of the Dudley Caving Club in the UK who agreed to take me deep underground. If you go deep enough underground, the air is remarkably fresh. The only odor that made an impression on me was the faint scent of sulfur released when we brushed against the limestone. The headlamps we used were powerful and illuminated a surprising amount of detail. If I hadn’t done it for myself, these scenes would have been wholly inauthentic and an armchair version of the real deal. Sometimes, it’s worth getting all gung-ho about research. Plus, it was an exhilarating experience—even if I was scared shitless.

Also, I didn’t actually climb Everest—that would have been a major recipe for disaster as I’m spectacularly unfit—but hiked to base camp. We were lucky; the weather held and, although freezing, we were able to see the mountain and its surrounds clearly and get a very good idea of the atmosphere and an awe-inspiring first glimpse of the Himalayas.

Researching a city or landscape online can be valuable, but you can’t necessarily absorb its unique atmosphere unless you experience it first-hand (although this isn’t always possible). Traveling through Tibet affected me deeply. The stranglehold the Chinese government has on the Tibetan people and its systematic attempt to dilute the culture is devastating to witness. Having lived in South Africa for twenty years, with its own brutal history, it was sobering to see this first-hand.

You explore horrors that are both physical and psychological. What do you see as being the relationship between the two, and how does their commingling benefit the telling of a story such as this?

Every action has a reaction, and people who willingly put themselves in dangerous situations—courting possible psychological fallout and worse—fascinate me, as I’m a coward at heart. This came through in the novel in the form of the “third man” factor—the sense that you’re being followed or accompanied by an elusive, benign companion when in dire straits. It’s a phenomenon that’s been documented by countless mountaineers and adventurers who have found themselves in life-threatening situations.

I was diagnosed with PTSD after a home invasion, and I used my experiences with the condition—for example, constantly being on high alert and anxious—as inspiration for Simon’s emotional fallout.

You often use satire in your books. In your opinion, what is the potency of humor, and how can it be used to effectively shed light on the absurdity of so-called “reality”?

I really appreciate you pointing this out—thank you! Not many people pick up on this. Our family has always dealt with tragedy and difficult situations using black humor, and we use it as our go-to coping mechanism. We’re constantly taking the piss out of ourselves.

This bleeds into all of my writing, but clearly, it’s risky injecting satire or humor of any kind into a novel because not everyone gets it—it’s so subjective. I was also well aware that focalizing the narrative through an unsympathetic character was a risky strategy (Simon makes some terrible decisions and isn’t what you’d call “nice”). He uses snark and humor to take the edge off the horror he experiences, although this sometimes backfires on him.

In addition to being a novelist, you are a screenwriter. How do these disciplines inform one another, and what do you see as being the greatest difference in execution?

In some ways screenwriting is a tighter discipline—you don’t necessarily have as much room to explore a character’s motivation, and you often have to get to the heart of the matter with more economy. I’ve recently had the great privilege of working on an adaptation with a screenwriter who is top of his game (I won’t say who in case the project goes south!), and one of the most valuable things he taught me was that screenplays, especially for long-running TV series, can hoover up story at an alarming rate. For example, a four-hundred-page novel might only translate to a couple of hours of valuable screen time. It’s been a real learning curve for me.

You have a “fondness for the macabre.” To whom (or what) do you credit this interest? Also, how do such creative influences make their way into your fiction?

I blame this entirely on Stephen King. He excels at putting ordinary characters in extraordinary situations. I’ve always been drawn to the darker side of life—it’s just the way I’m wired.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Sarah Lotz is a novelist and screenwriter with a fondness for the macabre. She is the author of Day Four and The Three, and she lives in Cape Town with her family and other animals.