Research is possibly my favorite part of the writing process. It delays the hard part—the writing words part—indefinitely. (Note to editor: that is a joke.) But also, I want to get it right, especially when it comes to police work.

We’ve all encountered stories where the police work is glossed over so heavily it’s distracting, like on one of those TV detective squads with a giant, wall-sized computer screen that solves their cases for them—The Crime-O-Matic, I call this—or far-fetched gaps in procedure or plausibility that distract from the plot. Creative license is good, and necessary, but realistic details are essential for fully developed characters, settings, and situations.

That’s what led me to the Columbus Police’s Civilian Ride-Along Program. I’d already Googled my heart out regarding police procedure, and now I just wanted to see how it worked, hear how cops talked to each other. You can’t exactly Google, “What does a squad room smell like?” or “Does the ladies’ room of the police impound lot have toilet paper?” But, I can answer both of those after my experience. (Answers, respectively: pizza and coffee; no.)

On a Sunday morning in August, I become a thirty-seven—that’s the ten-code for a ride-along, aka a giant pain in the ass. Even worse when I say I’m a writer and not, for example, something respectable like a sociology grad student doing a thesis project.

The midwatch shift sergeant assigns Officer Mike the honor of babysitting me all day. To his credit, he doesn’t roll his eyes or sigh, even though he tells me later that he got stuck with me because he’s the junior man on this shift, fresh off a transfer from another division—meaning he was getting the crap nobody else wants: bodies in ninety-degree heat, local nutballs reporting Martian robberies. A thirty-seven isn’t anyone’s idea of a good time, but he just shrugs and motions for me to follow him out to his cruiser.

“Two things,” he says as we settled into the front seat. He’s in his late thirties, stocky, short greyish hair. His face is serious, but his blue eyes have good stories in them. “One, if I say do or don’t do something, you gotta listen.”

I nod.

“Two, anything happens to me and we need help, you push this right here,” he says, pointing to a red button on the radio, “and you say ten-three. Got it?”

“Two, anything happens to me and we need help, you push this right here,” he says, pointing to a red button on the radio, “and you say ten-three. Got it?”

“Ten-three.”

“Right.”

“What’s that?”

“Officer in trouble,” he says, not kidding. Then his expression lightens. “But if you thought you were gonna see stuff on a day shift, you’ll be bored out of your mind today.”

Police work, it turns out, is a lot like other work sometimes: boring.

Aside from the red button, that is.

Our first call is a domestic disturbance at a row of townhouses where a father and son have gotten into a fight. I came into this thinking I might have to watch from the car, but Mike lets me follow him to the sidewalk where we listen to the kid tell his side of the story. It’s not much of a story, and he’s not much of a kid anymore—twenty, but narrow-chested and shirtless, slumped on a crumbling retaining wall in a pair of dusty velour pants. “He poked me in my eye,” the kid says. “I’m sleeping and he walked in and poked me in my eye. What the hell is that?”

“You slapped your father in the face,” Mike says. “That’s why we’re here.”

“Because he poked me in my eye,” the kid repeats. “That’s why I hit him. You think I deserve that shit? To be poked in my eye on a Sunday morning just because I didn’t do the dishes yet?”

Behind him, on the porch, the father yells, “Lazy-ass.”

The kid looks up at Mike again. “I’m not apologizing,” he repeats, less confident this time. There is an air of frustration around him, like the eye-poking incident is just another in a pattern.

After a bit of wheeling and dealing, the kid agrees to cool off at a friend’s house, and the father agrees not to press charges for the alleged slapping. We get back into the cruiser, and Mike tells me that the Twelve-Precinct is full of rundown neighborhoods like this, full of go-nowhere domestics that basically amount to two equally guilty, equally stubborn individuals who need a referee instead of a cop. But the cops are the ones who make house calls, and so…

Mike has been a cop for 14 years. He spent the last 5 years working in Narcotics, where he mostly dealt with complaints about drugs being sold from bars and would work on small scale investigations into such. He switched back to Patrol because midwatch is a shift with good hours—9 to 7, 4 days a week. This is the first time in 14 years that he hasn't been stuck on an evening or night shift.

He explained why: everything in the department is based on seniority, except it's a bit extreme. Say you and I were both hired into the department. You got hired on Monday, and I got hired on Wednesday. Unless I get promoted beyond your rank (by taking the sergeant's exam, or whatever), you will always have seniority over me, and therefore you would get first dibs on better assignments regardless of merit.

Read about Allison Brennan's time training with the FBI for research!

Mike tells me that cops pretty much have carte blanche over how they spend their time when not specifically dispatched on a call—which they refer to as “runs.” A go-take-a-report-about-a-stolen-lawnmower-type call is a “paper run,” because it's basically just a report, nothing too wild. Something more lively, like a violent altercation outside a bar, is called a “gun run.” Anyway, when not on a run, it's up to the officers whether they do traffic stops, run speed traps, sit somewhere and read a magazine, drive around looking for trouble, etc.

Mike likes to pull up a list of stolen cars (using the computer in the patrol car, which is quite the powerful machine) and pick out a handful of cars to be on the lookout. For instance, we looked for a “maroon or burgundy Olds 88” today that was taken in a robbery. (In this context, robbery means carjacking.) Some of the stolen cars had license plates attached to their entries, and some did not. Anytime we saw a car that might fit the description, Mike would run the plates to see what came up in the database. We don’t recover any stolen cars, although he said he usually finds about 1 a week in this way.

We get an assault call next—a man got hit in the head by a guy on a bicycle and then passed out in the street. We arrive at the same time as an ambulance. The man is disoriented, agitated, and jumping around shouting things even though he is bleeding from the head. He is taken to Grant Hospital in the ambulance, and we follow them there.

After Mike enters most of his report into PatrolView (which takes forever because Mike types with one finger and, also, because the system is notoriously fiddly—“this is what happens when a bunch of cops attempt to patrol the information highway”), we went into the hospital to talk to the victim. He declines to press charges because, he says, “I'm in the game.” Mike explains that this is thinly veiled code for being involved in drugs or gang life.

We get sandwiches for lunch at a deli and take them back to Twelve-Precinct, where we watch a little bit of True Lies on television. The place looks like my high school. Kinda crappy, some tables, a vending machine that doesn't work well. It gives Mike a bottle of water when he selected a Gatorade. I select and receive a Diet Coke, but when I open it, it explodes everywhere. ”That's what happens when you get want you want,“ Mike says. ”Payback.“

Mike is very wise.

After lunch, we follow up on a report of a stolen car after the victim said her car had been returned. Mike predicts in advance the following, apparently common, scenario: a drug user loans her car to her dealer (”dope boy“) in exchange for drugs. The dope boy uses the car to run errands or whatever and doesn't bring the car back in a timely manner. So the crackhead calls the police. Then, hours or days later, the dope boy brings the car back, and the victim has to call to cancel the report so she does not get pulled over for driving her own car later. After talking with the woman for a few seconds, it’s pretty clear Mike’s prediction is a decent guess. As we walk back to the cruiser, he whispers to me, ”Behold, my powers of detection.”

By now, it’s almost seven. Mike’s shift—and my adventure—are over. “See, told you it was going to be boring,” Mike says. But I’ve filled half of my notebook with details. Not about the criminal masterminds we failed to encounter, but about Mike himself, about the job, the paperwork, the un-Google-able things that I can’t wait to use to bring my characters to life. We shake hands, and he wishes me luck on the writing.

By now, it’s almost seven. Mike’s shift—and my adventure—are over. “See, told you it was going to be boring,” Mike says. But I’ve filled half of my notebook with details. Not about the criminal masterminds we failed to encounter, but about Mike himself, about the job, the paperwork, the un-Google-able things that I can’t wait to use to bring my characters to life. We shake hands, and he wishes me luck on the writing.

“Make me dashing,” he says. “In your book. Make me out like one of those dashing heroes. Deal?”

I say, “Deal.”

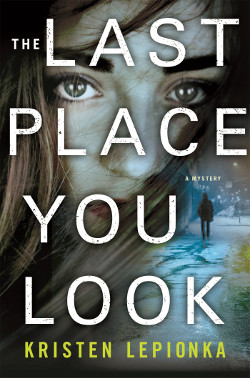

(Mike: hope I did all right. Check it out on June 13th.)

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Kristen Lepionka grew up mostly in her local public library, where she could be found with a big stack of adult mysteries before she was out of middle school. In the name of writing research, she has gone on multiple police ride-alongs, taken a lock-picking class, trespassed through an abandoned granary, and hiked inside an Icelandic volcano. Her writing has been selected for McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Grift, and Black Elephant. She is also the editor of Betty Fedora, a semi-annual journal that publishes feminist crime fiction, and lives in Columbus, Ohio with her partner and two cats.