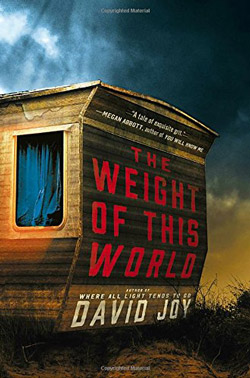

In The Weight of This World, David Joy returns to the mountains of North Carolina with a powerful story about the inescapable weight of the past (available March 7, 2017).

In The Weight of This World, David Joy returns to the mountains of North Carolina with a powerful story about the inescapable weight of the past (available March 7, 2017).

There’s a strong thread of uncompromising, dark fiction that's weaved its way back through the literary epochs. I’m not referencing trailblazing titans from Hemingway and Hammett to Cormac McCarthy and Daniel Woodrell, who certainly deserve their veneration, but, well try this: ask a devotee their preference of what we call gritty fiction, and I’m betting they will direct you to the side streets and alleyways alive with the works of Jim Thompson, Flannery O’Connor, Charles Willeford, and Dorothy B. Hughes, to name a few. Currently, writers like David Joy continue that stark, no bullshit tradition, and the author’s latest, The Weight of This World, builds richly on his debut effort, Where All Light Tends to Go, which was named an Edgar finalist for Best First Novel.

For many admirers of this blunt, unapologetic approach, it’s not just the tight plot with an economical use of words that constitute this style, but characters with a sobering realization that the fix is in—that life deals the majority a crap hand, and the chance of rising above the cesspool is highly doubtful. Weight’s prime example is Aiden McCall, who at twelve watched his dad gun down his mother and then take his own life. Despite the coarseness of the material, listen to the poetry in Mr. Joy’s prose (Reed Farrel Coleman calls it “a beautiful nightmare”) as this hardened Appalachian teen realizes the dice have been cast:

What scared him was what he knew in that dream. He seemed to have some unquestionable understanding, something seemingly divine, that ensured in time he would become his father. There are things passed down that escape reflections in mirrors, traits that paint the inside. Those were the things that he understood, and those were the things that he feared. What he heard before he shuddered awake each night were the words of God Almighty, the Lord God saying, “In the end, blood always tells.”

He ends up fleeing his foster home and living in a cabin in the mountains, scraping along on his own. Teenage wasteland ultimately gives away to adult listlessness.

Aiden’s best friend—ever since they stole packs of Pall Malls as kids—is Thad Broom. Thad’s own disconnect from the nuclear family is an aloof mother who allowed her live-in boyfriend to kick out the young Thad to live in a rundown trailer elsewhere on the property because he didn’t want to look at the kid anymore. Grown up, Thad goes off to fight the good fight in Afghanistan and returns a bitter veteran with a bad back.

Aiden is an out-of-work construction laborer following the implosion of the housing bubble, and he, with Thad’s help, begins stripping the copper from the very same abodes he’d built. Throw in Thad’s mother April—who is now in a relationship with Aiden, which really rubs Thad the wrong way—and these battered, traumatized individuals form a hardscrabble triumvirate.

Taking in some spending cash from the copper sales, they go to Wayne Bryson, their drug dealer, only to witness his accidental death—a pivotal moment that will alter their direction.

Wayne cocked the hammer and raised the pistol to his temple. “See?” He pulled the trigger and the far side of his face blew off. A thrash of blood, chunks like grayed hamburger, let loose across the room. His arms dropped to his sides, his right hand still clenching the Colt, and he held there for a second or two before he toppled stiff as a tree face-first into the coffee table, rapping the bridge of his nose on the way to the floor.

Their first inclination is to take their money and bolt, and they do, but then return with the idea there may be monetary gains to swipe—that’s when they discover they haven’t dropped as low as they can go.

Mr. Joy’s primary addendum to the gritty story subcategory (he has cornered the “Appalachian Noir” market) is realism. Aidens, Thads, and Aprils exist beyond the pages of Mr. Joy’s imagination. Not just the generational poverty of modern Appalachia or overall working-class disillusionment, but the cross-country tremor of drugs that’s undermining whole communities with authorities at a loss to stop it. A snapshot of this authenticity is vividly portrayed in The Weight of This World.

Read an excerpt from The Weight of This World!

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

David Cranmer is the publisher and editor of BEAT to a PULP. Latest books from this indie powerhouse include the alternate history novella Leviathan and sci-fi adventure Pale Mars. David lives in New York with his wife and daughter.

A week before the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee earlier this year, Matt Thistlethwaite was appointed assistant minister for the republic. For the first time, a government MP had been given the official task of making the case for Australia become a republic with an Australian head of state.