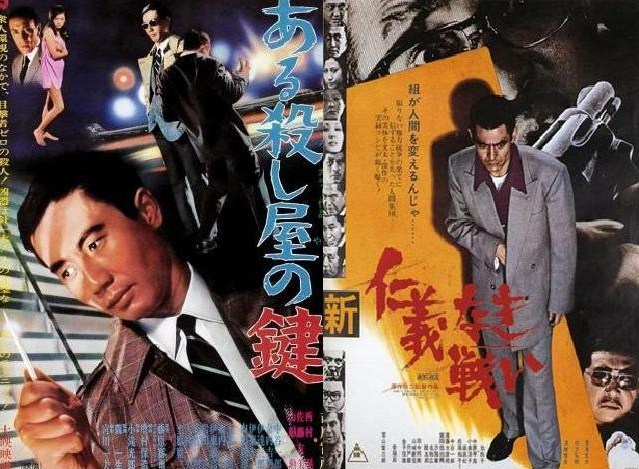

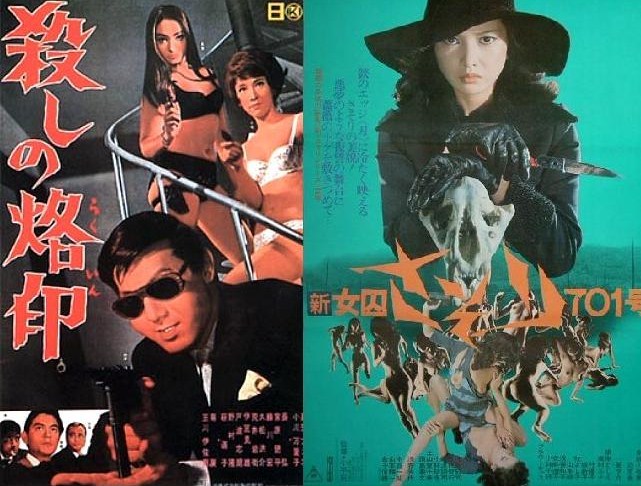

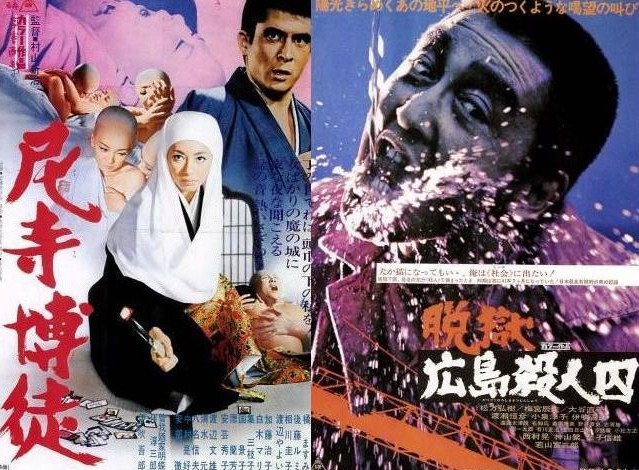

The anonymous designers of these posters are pioneers, experimenting with perspective, angles, color, and scale. Of course, the subjects and themes are quite inspiring—tattooed vixens, katana-wielding warlords, racketeering Buddhist nuns, shiv-brandishing thugs, and vigilante justice-dealers. The film titles, inked in the splashy kanji and hiragana characters, complement the photographic montage in charting a timeless, discordant, and imagined historicism—from swordsmen in feudal Japan in chambara films such as Zatoichi, Lone Wolf and Cub, Lady Snowblood to the yakuza antiheroes in hyper-modern action thrillers like Branded to Kill, Battles Without Honor or Humanity, and Tokyo Drifter.

One prevailing element that unites Japanese noir posters is ero guro, an aesthetic that unites the erotic and the grotesque. It is a graphic style seen in ancient woodblock carvings called Ukiyo-e dating to the Edo period in the 1800s (some examples being The Dream of Fisherman’s Wife by Katsushika Hokusai or Twenty-eight famous murders with verse by artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi). Death, decay, and degradation are seen as extreme allegories for deviant eroticism and unfettered sexuality. Of course, the sensationalism of ero guro, based on provocative exaggerations and profane absurdism, unavoidably also evokes a comical response from viewers. There is certainly an undertone of pitch black humor in exploitation noir—and perhaps in all noir.

I have not even scratched the tip of the iceberg that is the graphic richness of the noir genre, whether it is pulp cover art or cult film posters. The artistic movement brought on by the literary genre is so variegated that it cannot be summarily catalogued. One thing is for sure—the bizzare and beautiful, the lurid and lofty coexist in the visual, textual, and imaginary.

Images via Hanafuda and Lost Video Archive

Cathy Chen is inspired by post-war Japanese cinema and doesn’t believe in a fair game of hanafuda.

I like those posters.

Love this!