Forty years ago this month, Serpico hit movie theaters. It’s important to remember the context in which the film came into the world. The sixties had long since curdled into the seventies. New Jersey still bore the scars of the horrific Camden riots. Vietnam lay in ashes. The economy was entering a recession which would last until 1975. Watergate—which had begun as a small story about a burglary at the Democratic National Headquarters—had metastasized into a full-blown White House scandal. Just a month before, a sweaty Richard Nixon had gone on television to try and reassure an increasingly skeptical public that “I’m not a crook.” And in New York, the city was still reeling from the revelations of the Knapp Commission, which has exposed rampant systemic corruption in the police department.

Forty years ago this month, Serpico hit movie theaters. It’s important to remember the context in which the film came into the world. The sixties had long since curdled into the seventies. New Jersey still bore the scars of the horrific Camden riots. Vietnam lay in ashes. The economy was entering a recession which would last until 1975. Watergate—which had begun as a small story about a burglary at the Democratic National Headquarters—had metastasized into a full-blown White House scandal. Just a month before, a sweaty Richard Nixon had gone on television to try and reassure an increasingly skeptical public that “I’m not a crook.” And in New York, the city was still reeling from the revelations of the Knapp Commission, which has exposed rampant systemic corruption in the police department.

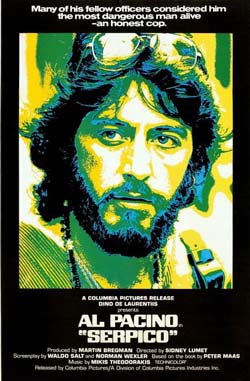

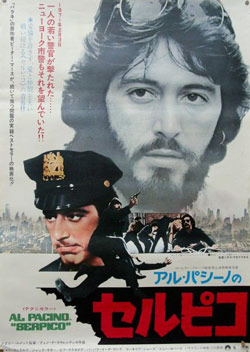

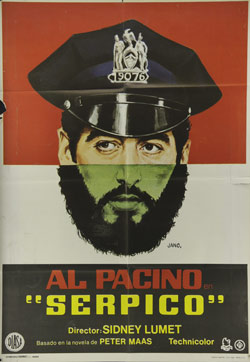

Into this swirl of bad feelings, Serpico was released. Directed by the great Sidney Lumet, from a screenplay by Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler based on the book by Peter Maas, it told the true story of the hero of the Knapp Commission findings, a brave cop named Frank Serpico. Frustrated with the corruption around him, Serpico had worked to expose the rottenness in the NYPD and nearly been killed for his efforts.

The film was released in the wake of the blockbuster success of The Godfather, and it shows. For instance, watching the film today, one wonders if the filmmakers of such a gritty city film would have chosen a score that leaned so much toward Old Country nostalgia. Nevertheless, the real connection with the earlier film is, of course, the presence of star Al Pacino. He was helping lead a wave of the unconventional leading men that included stars like Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman. Serpico—like his other film that year, Scarecrow—presented a sharp contrast from his career-making turn as Michael Corleone. It gave him a hit of his own and helped establish him as a serious actor and major star apart from The Godfather.

The film was released in the wake of the blockbuster success of The Godfather, and it shows. For instance, watching the film today, one wonders if the filmmakers of such a gritty city film would have chosen a score that leaned so much toward Old Country nostalgia. Nevertheless, the real connection with the earlier film is, of course, the presence of star Al Pacino. He was helping lead a wave of the unconventional leading men that included stars like Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman. Serpico—like his other film that year, Scarecrow—presented a sharp contrast from his career-making turn as Michael Corleone. It gave him a hit of his own and helped establish him as a serious actor and major star apart from The Godfather.

But does the film hold up forty years later?

Well, I’m not sure that it holds up in the sense that it plays the same way now that it did when it was released. It exists today as something of a time capsule in a way that The Godfather or a later Pacino/Lumet film, Dog Day Afternoon, do not. Serpico is very much the seventies story of an outsider—in fact, it almost has a Noir Western’s insistence on the unsociability of the hero. We see Frank Serpico in a variety of social situations, but we never see him become a part of any group. There’s a long scene at a party where we see him dancing and having a grand time with a bunch of bohemians, but the scene seems to be there to insist that he could be a part of the group if he were not pulled away by some deeper commitment and integrity.

Well, I’m not sure that it holds up in the sense that it plays the same way now that it did when it was released. It exists today as something of a time capsule in a way that The Godfather or a later Pacino/Lumet film, Dog Day Afternoon, do not. Serpico is very much the seventies story of an outsider—in fact, it almost has a Noir Western’s insistence on the unsociability of the hero. We see Frank Serpico in a variety of social situations, but we never see him become a part of any group. There’s a long scene at a party where we see him dancing and having a grand time with a bunch of bohemians, but the scene seems to be there to insist that he could be a part of the group if he were not pulled away by some deeper commitment and integrity.

In that way, despite the shaggy hair and hippie dress of its unconventional hero, Pacino’s Frank Serpico belongs to the cinematic tradition of virtuous outsider heroes that goes back to the days of hardboiled cops and private eyes. The film plays a bit like The Big Heat meets Easy Rider.

Where the film betrays the limitations of that era, however, is found in the scope of its representation. Black characters exist mainly as criminals or comic relief, and women exist in the film either as victims of crime or as witnesses to Serpico’s dogged integrity. We get the mandatory scene of a concerned female lover tearfully imploring our hero to stop caring so much about his job. We’re shown the aftermath of a gang rape mostly as way to demonstrate the stalwart nature of our hero in the face of such an atrocity.

The seventies are often seen as the second golden age of American cinema for good reason. The industry had survived the upheavals of the fifties (when the studio system, for a variety of reasons, came crashing down) and had, by the late sixties, begun to reinvent itself. Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese were among those directors who reconfigured the landscape of American film into something close to what we’re living in now—where our pop films are largely the offspring of Spielberg and Lucas and our “serious” films are largely the offspring of Coppola and Scorsese. I make this observation neither as a praise nor a criticism, but simply as an observation. I think we can acknowledge what these filmmakers did well without asserting that they were flawless. At the very least, one must recognize that while this era did indeed open up the movies from what they had been, the era also still left out many voices. (To digress a bit: It’s also probably a detriment to our cinema that great seventies filmmakers like Peter Bogdanovich and Hal Ashby—who made quieter and gentler films—haven’t had more influence.)

The seventies are often seen as the second golden age of American cinema for good reason. The industry had survived the upheavals of the fifties (when the studio system, for a variety of reasons, came crashing down) and had, by the late sixties, begun to reinvent itself. Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese were among those directors who reconfigured the landscape of American film into something close to what we’re living in now—where our pop films are largely the offspring of Spielberg and Lucas and our “serious” films are largely the offspring of Coppola and Scorsese. I make this observation neither as a praise nor a criticism, but simply as an observation. I think we can acknowledge what these filmmakers did well without asserting that they were flawless. At the very least, one must recognize that while this era did indeed open up the movies from what they had been, the era also still left out many voices. (To digress a bit: It’s also probably a detriment to our cinema that great seventies filmmakers like Peter Bogdanovich and Hal Ashby—who made quieter and gentler films—haven’t had more influence.)

In the end, it’s the nature of a motion picture to be a time capsule, for good and for bad. Truth be told, that’s probably the destiny of every movie. What will something like Serpico look like in another forty years? What about a hundred? Only time will tell.

Jake Hinkson, the Night Editor, is the author of The Posthumous Man and Saint Homicide.

I watched the new BD the other night, and thought it held up pretty well. Still one of my all-time favorite films.