Kevin Smith’s Dogma is a biting and insightful look at many mythologies and modern religions. And while some of it is a little sharp, there is insight in its critique as well. Smith attempts to present a unified system of mythological entities borrowed from different cultures. This idea, though, is not his own, as nearly every culture in the world attempts the same in order to justify its own cultural supremacy.

Smith borrows Loki from Norse mythology. As anyone who is familiar with Marvel’s Thor (the comic or the film adaptation), Loki is not really a nice guy. He wants to destroy things, play tricks, and generally just cause mischief. The angel in Dogma, then, is a perfect incarnation of Loki, but Matt Damon's version has been reassigned to be an angel instead of a pagan deity.

Likewise, Salma Hayek’s Muse is not a Christian concept. Rather, the Muses were the offspring of Zeus from Greek mythology. Her role is exactly the same—to inspire the arts—but the parentage is changed to bring her in line with the Christian idea of one God and the angels who serve Him.

The reassignments are subtle, with Smith attempting to pass them off as the way things have always been. These characters know the truth—and have always known this is the way it was—and humanity has somehow confused things by assigning Loki and the Muse to pagan mythologies. This idea is nothing new to mythology, though. Most cultures go through an assimilation process as their culture spreads.

The ancient Greeks were particularly adept at this as they spread out across the islands. Each island had its own distinct culture and regional deities. As the Greeks conquered, they craftily realized that there was no reason to strike them down to get them to worship Zeus—they could win through guile. It might have gone something like this:

“Have you heard the good news about Zeus?”

“Well, sir, I’m sure he’s a fine god, but we worship Apollo.”

“Do you? Well, that’s great! Apollo is the son of Zeus; the gods are all related, so really you worship Zeus anyway.”

“Is that so? Well, come in and have some pie and tell me all about Zeus.”

Alright, I might have made up the bit about pie. But, by explaining that all of these regional gods are related to Zeus, Greek culture spread without overwriting the existing culture. It also explains why Zeus slept around so much; he had to father the other gods.

The Romans, rather than coming up with their own gods, adopted the Greek pantheon, wholesale. They simply changed the names and tamed and civilized them to fit Roman sensibilities. Those famous Bacchanalias had nothing on the parties Dionysus threw.

When Constantine converted to Christianity, the entire empire had to switch from Roman to Christian. Christmas replaced the Saturnalia festival, and the numerous saints of the Catholic Church were created to mitigate the pagan need to pray to specific deities for specific needs—kind of like a prayer telephone switchboard.

Cultural assimilation can make it difficult to truly know if the mythologies have been updated with the new version. The concept of authorship and copyright didn’t arrive until the 20th century. Before that, writers and editors were free to add on to stories. Consequently, it can be difficult to find the different narrative threads in stories such as Beowulf, which is clearly an assimilation of Norse and Christian mythology.

Some people will cry out that this kind of cultural appropriation is wrong. But the morality of such assimilation never entered into the equation. This is what cultures have done to one another throughout history, and just as language is subject to changes brought about by time and shifts of the culture, the cultures also change through time with what happens.

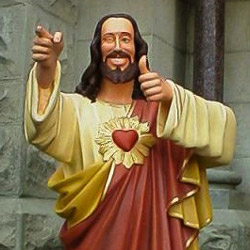

Smith takes the model of cultural assimilation and also uses it to expand the mythology, as well. He introduces Rufus, “the 13th Apostle,” who always existed but was edited out because of his skin color. Likewise, through Rufus, Smith states that Jesus is also black and that the hundreds of years of art history, which portray him as white, are incorrect—a whitewashing by Medieval Europeans who were predominantly white. Still not content, Smith pushes further, claiming that God is, in the current form, female and that genders don’t apply to God in the way they apply to humanity.

Dogma demonstrates cultural assimilation as a force of history, an inevitable change to ideas and cultures throughout time, both conscious and unconscious. Concepts of accuracy and authorship were fluid in the ancient world, with many stories going through dozens of incarnations to become what we recognize today.

Dogma challenges the idea that mythology is static. Mythological stories change, going through dozens or even hundreds of versions as the culture and people wrestled with ideas of their own existence. When cultural assimilation takes place, the best ideas are the ones that survive, and the new mythology takes its place. However, the dogma—the absolute, unquestionable religious beliefs—forbid this from happening, which is what prompts Rufus to speak the heart of the film:

“I think it's better to have ideas. You can change an idea. Changing a belief is trickier.”

Andy Adams is an adjunct professor of English at various colleges in the Phoenix area. He has an affectation for fedoras as they complement his villainous goatee. He’s been known to poke his head onto Twitter @A3Writer, but he’s never been big into birds. He blogs at A3writer.com about writing, teaching, and the conquest of fictional worlds—they’re more fun than the real world.

Read all posts by Andy Adams for Criminal Element.