The Dark Knight: Looking Back at Christopher Nolan’s Superhero Crime Epic

By Peter Foy

July 18, 2018

It’s hard to believe it’s been a full decade and three presidential administrations since the summer of 2008, the movie season that bestowed upon us The Dark Knight. Honestly, the memories one can have of this time—both for fanboys and the uninitiated—still feel so fresh. Christopher Nolan’s second Batman film was accumulating massive amounts of anticipation in the months leading up to its release—largely due to the untimely passing of star Heath Ledger in January of that year—and advanced word on The Dark Knight was setting it up to be a masterpiece that the mainstream would cherish unanimously. Nolan’s previous take on the character, Batman Begins, was welcomed with open arms by both critics and fanboys, and the trailers released for The Dark Knight were mouthwatering, to say the least. The three-year gap between Batman Begins and The Dark Knight wasn’t always met with patience, but when it finally premiered on July 18, the end result proved well worth the wait—and then some.

The Dark Knight indeed proved both a financial and critical success, and in fact, that’s a bit of an understatement. The film would go on to gross over $1 billion worldwide, making it the world’s fourth highest-grossing film at the time of its release, without accounting for inflation (it’s now the 35th, which is still nothing to sneeze at). Critics’ responses were glowing, calling it a masterpiece and even a highly relevant piece of social commentary, which was nigh unheard of for a non-Shakespearean film featuring men in tights. The Dark Knight is even likely to blame for encouraging the Academy to expand the number of Best Picture nominees, as there was a small uproar after the film got snubbed from the year’s shortlist. Looking back at the film, despite all its escapism, it’s almost a misnomer to call it a superhero movie—especially given the current template being used now. The Dark Knight was absolutely a genre film, but its basis was more crime fiction than anything else.

Go back to the film’s opening sequence: a bank heist rivaling some of the best in cinema in terms of complex writing and spectacle. The pacing and editing of the sequence are perhaps Nolan’s most impressive. And while it still feels like a comic book at times (like when we discover that the bank robbers have been asked to anonymously murder their partners at certain points—pure diabolical!), it’s never distracting and always feel fitting of Nolan’s idiosyncratic take on the Batman mythos. Featuring car chases, shoot-em-ups, and plenty of finely-dressed gangsters, The Dark Knight also appeals to those that miss ‘70s crime films like The French Connection—especially since Nolan mostly eschewed CGI, resulting in a far grittier feel. It’s still a little hard to understand how the movie got away with a PG-13 rating.

Plus, the film has what is easily the best movie villain of the new millennium; Heath Ledger’s highly original turn as The Clown Prince of Crime is still as remarkably terrifying as it is magnificent. Just writing this paragraph, I’m reminded of the Joker’s slew of unforgettable quotes that ran up and down my Facebook feed during that third weekend in July of 2008. (“Why so serious?”; ”Let’s put a smile on that face!”; “I believe whatever doesn’t kill you, simply makes you … stranger.”) The character’s fractured mannerisms (perhaps most iconic is the prevalent licking of his facial scars) and fiendish voice truly paint him as a most menacing enfant terrible, but there is an undeniable method to his madness. Respecting the comics by keeping The Joker’s motives murky, The Dark Knight’s true threat is ultimately enigmatic, allowing for a film that is both timely and timeless.

Crime writer James Ellroy once said that the tropes for most crime fiction stories would be preposterous in real life, but when executed properly, they can reflect our real world in an engaging and subversive way. The Dark Knight is a perfect example, as its powerful sense of tension and strategic violence ultimately aid the movie’s prevalent themes. The film’s opening visual of the Batman signal emerging from a blast of blue-shaded flames with no musical accompaniment perfectly sets up the movie’s underlying concern for an escalating chaos.

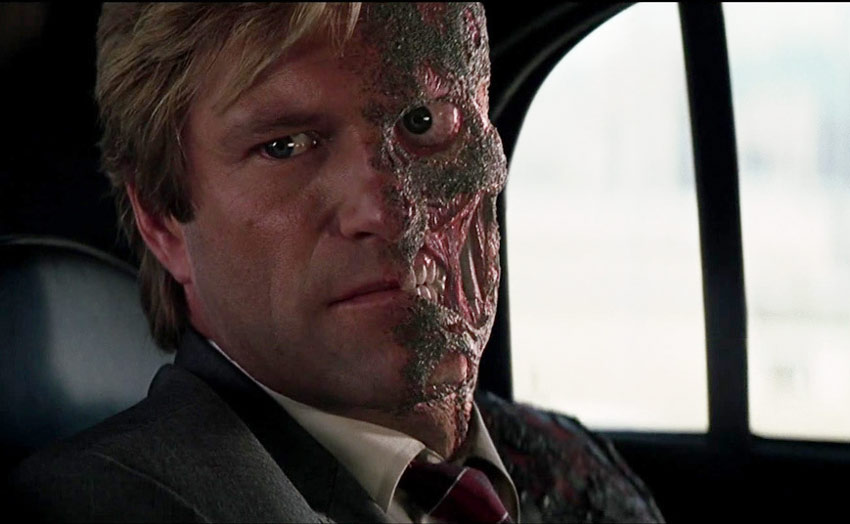

However, watching The Dark Knight after having seen Batman Begins, it’s immediately evident that the previous film is much darker in terms of lighting. The Dark Knight’s first two-thirds make use of brighter color grading, which reflects the city’s more hopeful ideology in light of Harvey Dent’s upcoming election. The more dismal lighting in the film’s final act reflects Gotham’s impending doom after Harvey Dent transforms into the corrupt Two-Face. While the film has often been thought to be about the effects of 9/11, its subtext remains palpably relevant within our current political spectrum. Released in the same year that Obama took office, it’s miraculous to consider how prophetic The Dark Knight really is.

Was it perfect? Hardly. It doesn’t take more than two viewings to realize that the film had a far messier second half. Perhaps the film’s most damning criticism is that it seemingly had two third acts. Also, there was at least one plot hole that seemed like lazy writing (after Batman saves Rachel after being pushed out the window by the Joker, why weren’t we shown what then happened to Joker, his cohorts, and the partygoers they were holding hostage?). Still, the film is so powerful as a whole that concern over these slight missteps just seems like nitpicking. The Dark Knight doesn’t have what you might call a happy ending, which in many ways makes the film very comparable to The Empire Strikes Back. Both are sequels to massively successful summer blockbusters that managed to outdo their original by letting the bad guys win. To be honest, I don’t think a superhero movie ending has moved me like The Dark Knight—until this summer’s Avengers: Infinity War.

Perhaps the real reason why The Dark Knight phenomenon remains so untouched in our memories, however, is that it continues to be an anomaly in the world of comic book movies rather than an adjustment of the status quo. Two months prior to the release of The Dark Knight, Marvel Studios released Iron Man, and as we all know, this started the Marvel Cinematic Universe that more or less grew to encompass all of Hollywood’s superhero ventures (also, in case you forgot, Disney ended up purchasing Marvel just a year later). There’s no question that Iron Man was the more impactful of the two films, especially since most other superhero films that have tried to mimic the morose tone of The Dark Knight have ultimately upset both fans and critics (e.g., Man of Steel, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, Justice League—most subsequent DC properties if we’re being honest here).

Still, The Dark Knight has proven to be perhaps the single most memorable superhero film—if only because it was the closest of its genre to satisfying everyone. It felt enough like high art while also being thrillingly escapist, and it’s ultimately the perfect reconciliation of Nolan’s early and latter-day work.