A fairy story.

But it was nothing to do with those flittering Tinkerbell types who gave you three wishes or left money for your milk teeth, because I was a melancholic child, a lover of banshees, devils and ghosts. And Irish fairies were irksome, wicked types, who’d sour the milk, stop the hens from laying, even lame a farmer’s cattle and if they were feeling very malevolent, they’d replace your baby with a changeling. Feys and shape shifters who’d creep into the farmhouse, upturn a pail, kick over some pans for good measure and then sneaking up to a crib, peel back the covers and take the child, leaving something evil behind. Sure, it’d looked like your own but it was a horrible, evil creature who’d bring nothing but bad luck.

When I was a little girl, I believed in fairies. I’d spend all day up at the fairy fort in the shadow of the Cuilcagh Mountains, watching and waiting but keeping my head down, lest they see me because God knows if I was to cross them, I’d be dragged down into the Fay World forever. So no surprises then when my Grandad started up with, “Are you a witch or are you a fairy? Are you the wife of Michael Cleary?” that my mouth was agape and you could have heard a pin drop.

It was 1895 and it had been a long, cold winter, the coldest on record and after one of her jaunts, just a few days before St Patrick’s Day, poor Bridget must have caught a chill in that blustery, freezing weather because she was taken very ill. Her husband, Michael Cleary who was a cooper, made her a pot of tea when she finally got home and to told her she should take to her bed. But still she shivered, tossed and turned and the next day, Bridget complained of the most violent headache. She grew worse and developed such a raging temperature, she didn’t know where she was.

As the week wore on and his wife became sicker, Michael Cleary summoned a doctor but for whatever reason, the doctor didn’t come. Meanwhile, neighbours came and went to the cooper’s cottage, bringing with them food, good intentions and prayers. But all this time, Bridget didn’t improve but stayed her in bed, oblivious. Michael meanwhile, watched his wife getting sicker and sicker, more and more feverish by the minute. She was delirious, speaking in strange tongues and not knowing her own name. He feared for the worst, but then his cousins suggested he needed another kind of doctor altogether. They gave him the name of a man called Jack Dunne who they said was, “a miracle worker.” Others in the town called this old boy a “fairy doctor.” Jack Dunne was a weaver of spells, also known as a “shanachie” (a storyteller) and when he arrived at the cooper’s cottage, he asked to be taken to the sick woman’s bedroom immediately.

His eyes were weak and though he’d never met the woman before, claimed he could see at once that Bridget Cleary was “not herself.” He’d heard, of course, that she was a well dressed woman but this creature was a terrible mess, with hair all over the place like some sort of banshee. So he told the husband, “Your wife’s not herself today. But I’ve something that will bring her back. Don’t you worry,” he said, because he knew the truth of her illness and this wasn’t Bridget Cleary at all.

She was gone, he said, “away with the fairies” and this creature, sweating and rambling before them, was a changeling.

“I want my wife back. Bring her back,” said the husband.

“I’ll bring her back alright,” said Jack Dunne, telling those gathered to make a fire in the kitchen, whilst instructing another heavier one to sit on her legs, so that her husband could yank open her mouth and tip the medicine down, whether she liked it or not.

“Take that, you rap!” said Jack Dunne.

Another shouted, “Take it, you old bitch or we’ll kill you!”

And the fairy doctor wailed incantations as Bridget tried to fight and Jack Dunne insisted, “Away she go! Away she go!”

But none of it was working, so they dragged the poor woman into her kitchen, threw a bed pan of urine over her with, “Away with you. Away with you…” and then they slapped her really hard to drive the changeling out. “Who are you?” they screamed in her face but Bridget just sobbed and still didn’t know her name.

So, only one thing for it.

Fire.

Fire would drive the fairy out and so Bridget was dragged towards a red hot poker which was burning in a grate.

“Away she go! Away she go!”

“Come home, Bridget in the name of God,” somebody cried, as they held her near the fire.

What happened next, nobody seems to know but Michael Cleary was found by a priest in the local church, a day or so later, kneeling in front of the alter, praying like a mad man and when the Father asked, “Is your wife alright, now? I heard she’d been sick,” Michael turned around with a wild look in his eyes, saying , “I had a very bad night, Father and when I woke up, my wife was gone. I’m thinking the fairies have taken her.”

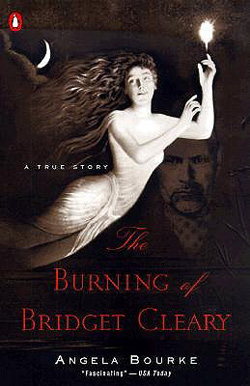

But the Father wasn’t having any of this fairy nonsense and he called the police. And on that day, 22nd March 1895, the charred and mutilated body of Bridget Cleary was found nearby the fairy fort in a makeshift grave.

Michael Cleary and eight other people were charged with Bridget Cleary’s murder. The coroner confirmed death by burning, but also detected signs of previous abuse. There were rumours that this strong and independently minded woman had been meeting a lover up near the fairy fort, and that Michael Cleary had used this opportunity with his spurious claims of fairies, to get rid of troublesome wife who, after nine years of marriage, hadn’t even borne him any children. Michael Cleary denied having murdered his wife, although he did admit to “driving out the fairy.” The real Bridget, he said, would soon be found at a nearby fairy ring riding a white horse, where he would be waiting to bring her home.

The ensuing investigation, legal battle and public scandal surrounding the case sparked a national furore at a time when Ireland’s ability to self-rule was being hotly contested. How, asked the English, could people who still believed in fairies be trusted to govern themselves?

Luckily for Cleary, he met a lenient judge and although he burned his wife alive he was convicted not of murder—which carried the death sentence—but of the lesser sentence of manslaughter. He was sentenced to twenty years in prison. On receiving his sentence, it was reported that Michael Cleary wept bitterly, shouting from the dock that he was innocent.

D.E. Meredith is the author of the historical crime series The Hatton and Roumande Mysteries, featuring the first forensic scientist, Professor Adolphus Hatton, and his trusty French morgue assistant, Albert Roumande.

I remember the nursery rhyme well. It’s right up there with Lizzy Borden: “Are you a witch, or are you a fairy,/Or are you the wife of Michael Cleary?” The sad part of the entire episode (besides the obvious) was that it took place at the very time that there was a growing movement in England to resolve “The Irish Question” by considering Irish Home Rule. The sensationalism of the Cleary incident and trial, allowed the Home Rule opponents in the English Parliment to label the Irish as a race that swung from trees and believed in the supernatural. Stereotypes alway hurt and the belief in this one led to thousands of deaths on both sides in the ensuing century.

Spot on comment above. This case fuelled a range of prejudices re: the role of women (Bridget was strong minded and financially independent – did this lead partly to her death?); the “feckless, superstitious” Irish (as deemed by the British press at the time). It had far reaching consequences, as Terrie points out.